|

|

Jewish World Review / August 28, 1998 / 6 Elul, 5758

Paul Greenberg

DO SOMETHING EVEN IF IT'S WRONG. Maybe that old sailor's axiom

explains Boris Yeltsin's latest 180-degree tack. Nothing else

does, including another vodka binge. For no drunk would do

anything so mundane: The Soviet president has just

reappointed the same prime minister he fired five months

ago. It's like Bill Clinton deciding to appoint Bernie Nussbaum

his new/old counsel.

The young banker, who's clearly no politician, was supposed

to be able to carry out unpopular reforms because he had no

constituency to offend. He did just that -- and offended

everybody. The unpopularity of a reform, it turns out, is no

guarantee that it'll work.

Premier Kiriyenko's latest brainstorm has been to devalue the

ruble, as if it weren't sinking fast enough, and to let it float a

bit -- to the bottom. Right now it seems headed for the ocean

floor. Nope, not exactly an economic revival.

Maybe the International Monetary Fund would approve of

this devaluation and the austerity it has made even more

austere, but the Russians were less than enthusiastic. And

understandably so. They're the ones who must bear the brunt

of all this theoretically fine, but practically disastrous, reform.

Why is it that when struggling economies dutifully follow the

sage advice of the International Monetary Fund (devalue and

be damned) they don't get out of economic trouble, but

further in? See Indonesia.

And now Russia seems headed the same way as Indonesia

and much of the rest of Asia: straight over the cliff. So Boris

Yeltsin decided to do something, even if it was wrong, and

even if it was the same wrong thing he'd done once before.

Namely, bring back the ponderous Viktor Chernomyrdin and

the economy of inertia. At least the free fall shouldn't be as

rapid under a stodgy administrator who still thinks -- well,

plods -- like the Soviet apparatchik he once was.

Suddenly old party boss Chernomyrdin started to look good,

the way a recession does when compared with a depression.

Turning the clock back to mere inertia can sound like

progress when you're whizzing toward sheer disaster.

Moral: Not everything that works in the West may work in

the East. Whoever said never the twain shall meet may have

understood a thing or two about the relevance of culture to

economics. The happy notion that Russia could simply

replace dictatorship with democracy, and a command

economy with private enterprise, always did have its

limitations. One might as well try slipping a computerized

16-valve under the hood in place of an old slant-six -- with no

thought about what else has to be changed to make the old

jalopy run. In this case, nobody, at least nobody in charge,

seems to have considered the traditions, expectations and

mentality of a whole people. As if the economy could be

divorced from the old culture. Or the old power structure.

Not all the whiz kids in the world, including a bright young

Russian banker suddenly proclaimed prime minister, may be

a match for the natural skepticism -- and passive aggression --

of the Russian people. Align both the country's peasantry and

its power structure against a leader, and who's left for him to

lead -- Russia's still meager technocracy?

And so Boris Yeltsin did something if only to be doing

something, and even if it was the same old thing. Going in a

circle is better than heading straight down, the way a tailspin

is preferable to a straight-down dive. Boris Yeltsin may have

lost his popularity, but he still has his wile. He knows that

change, any change, can keep hope, or at least interest, alive.

So he's taken a step -- even if it's a step backward.

Anyone who thinks this kind of politics -- and economics -- is

limited to mad Russians might recall what an American

president did in the depths of the Depression, when any

change would have been an improvement. Not even Franklin

Roosevelt stuck with his New Deal, or at least not with all of

it. He, too, changed course 180 degrees, and more than once.

FDR abandoned his loose talk about balanced budgets when

confronted by a country on its back. And he dropped even

the centerpiece of his economic policy -- the National

Recovery Act, with its blue eagle and price floors -- when it

didn't work out, constitutionally or economically. Time after

time, FDR headed in new and sometimes old directions,

following no policy but bold and persistent experimentation.

Franklin Roosevelt didn't succeed in ending the Depression so

much as in outlasting it. And he did it in no small part by

keeping the country hopeful, or at least interested. ("What in

the world is That Man going to do next?'') There's no telling

what Boris the Mad will do next, either. He keeps the world

guessing, even mystified, and therefore involved. Perplexity

beats despair any time. Anything does.

FDR was a lot better at pulling aces out of his sleeve, or

maybe just jokers, than Boris Yeltsin is. But this Russian joker

knows that consistency is the hobgoblin of small,

unimaginative minds. Sometimes going backward is the only

way to go forward, or at least survive till one can. So now this

Russian president and perplexity has reinstated an old

workhorse who's done nothing but plod. Yet at least under

Viktor Chernomyrdin's non-leadersip, some reforms were

made despite his opposition, while his replacement gave all

reforms a bad name.

When this country's president leaves his own chaos for

Russia's next week (at last Bill Clinton will get a real vacation),

he'll find that there are degrees of chaos in the world, and

that Russia's is the serious kind. Ours is only a crisis of

leadership; Russia's is a crisis of the whole system -- political

and economic, legal and philosophical.

To quote one Moscow daily, Sevodnya: "You can

poke as much fun as you like at American moral hypocrisy

and the desire to drag out the presidential dirty laundry

before a wide public. But in all this, note one obvious fact. If

the president feels obliged to explain himself to the nation on

live television even for adultery, the nation can be calm about

the future of the national

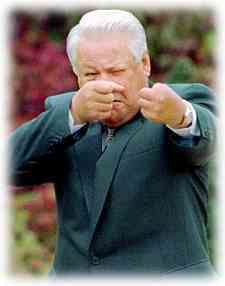

Boris Yeltsin's mind:

Boris Yeltsin's mind:

a riddle pickled in an

enigma

Five months ago, Boris the Mad replaced Viktor

Chernomyrdin, a Leonid Brezhnev without the charm, as his

prime minister. As a replacement, the always surprising

Russian president chose an antiseptic young banker because,

said Mr. Yeltsin, he wanted change. He must have wanted it

in the worst way, because that's how he got it. Under this

bright new, Western-approved reformist premier, Sergei

Kiriyenko, the Russian economy has gone from bleak to

catastrophic.

Imagined or not,

Yelstin has missed the mark ---

big time!

8/26/98: Clinton agonistes, or: Twisting in the wind

8/25/98: The rise of the English murder

8/24/98: Confess and attack: Slick comes semi-clean

8/19/98: Little Rock perspectives

8/14/98: Department of deja vu

8/12/98: The French would understand

8/10/98: A fable: The Rat in the Corner

8/07/98: Welcome to the roaring 90s

8/06/98: No surprises dept. -- promotion denied

8/03/98: Quotes of and for the week: take your pick

7/29/98: A subpoena for the president:

so what else is

new?

7/27/98: Forget about Bubba, it's time to investigate Reno

7/23/98: Ghosts on the roof, 1998

7/21/98: The new elegance

7/16/98: In defense of manners

7/13/98: Another day, another delay: what's missing from the scandal news

7/9/98:The language-wars continue

7/7/98:The new Detente

7/2/98: Bubba in Beijing: history does occur twice

6/30/98: Hurry back, Mr. President -- to freedom

6/24/98: When Clinton follows Quayle's lead

6/22/98: Independence Day, 2002

6/18/98: Adventures in poli-speke