|

|

Jewish World Review / June 30, 1998 / 6 Tamuz, 5758

Cal Thomas

PERHAPS NOTHING IS MORE AMUSING or more pathetic than

adults determined to force adolescents to do their bidding.

The defeat of the tobacco bill in Congress and pledges by the

Clinton administration to continue to search for ways to

"save our children" from the ravages of tobacco smoke and

addiction to nicotine will be about as effective as Prohibition.

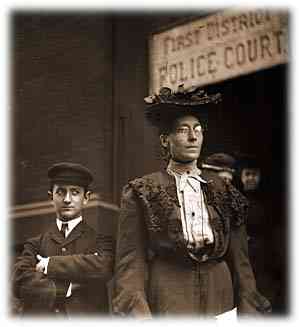

Today the crusaders are named Bill Clinton, C. Everett Koop

and John McCain. More than 90 years ago there were

Chicago's Lucy Page Gaston and her Anti-Cigarette League of

America. Gaston's crusade

In the beginning, she seemed to be making progress. Cigarette

production peaked at 4.9 billion units in 1897, but by 1901

fewer than 3.5 billion were produced. Gaston's crusade

helped produce laws against smoking, including some that

targeted women only (New York City passed the Sullivan

Ordinance in 1908, prohibiting women from smoking in

public; other municipalities followed New York's example).

For many, such laws only added to the allure of cigarettes.

This forbidden-fruit factor, coupled with the aura of danger

surrounding cigarettes, and men who smoked while away in

World War I, contributed to more, not less, smoking. States

like Arkansas, Idaho, Iowa and Tennessee repealed their

anti-smoking laws in 1917. The defeat of the anti-smoking

crusade was a forerunner to the repeal of Prohibition,

another attempt to regulate a form of human behavior that

encountered strong resistance.

As historian Robert Sobel recounts in his book They Satisfy:

The Cigarette in American Life, Gaston toyed with the idea

of running for president. Her platform sounded like a

forerunner of the Christian Coalition: "clean morals, clean

food and fearless law enforcement." There was even an

anti-Communist angle. Gaston believed that cigarettes were a

Bolshevik plot because some brands had been imported from

Russia.

Gaston was appalled when Warren Harding -- a cigarette

smoker -- was elected president in 1920. She said Harding

had a "cigarette face" (a diagnosis invented by Gaston). She

predicted Harding would come to no good, that his

administration would be laced with corruption, and that

Harding would even die in office before the end of his term

(he did, but not from cigarette smoking). Gaston was struck by

a trolley in 1924 and later died. Her doctor said the cause of

death was not her injuries, but throat cancer, though there is

no indication she was a smoker.

Sobel notes that when she started the National Anti-Cigarette

League, 4.4 billion cigarettes were consumed. The year she

died, more than 73 billion cigarettes were sold.

In 1905, the New York Times had editorialized against one

proposed anti-cigarette law in Indiana, calling it "fussy

legislation" and "as scandalous an interference as can be

conceived with constitutional freedoms." Today The Times,

which flipped on abortion, has also flipped on cigarettes,

believing teen-agers can be dissuaded from smoking without

regulation of the "cool" factor.

It is unlikely that today's anti-tobacco crusaders and

politicians will be any more successful than Lucy Page Gaston

and her followers. Adults telling kids they don't want them to

smoke will likely encourage them to puff even more. What

was that about those who learn nothing from history are

doomed to repeat

Smoke gets in their eyes

Smoke gets in their eyes

paralleled the work of the

Women's Christian Temperance Union, from which she

emerged to lead her own campaign to stamp out cigarette

smoking. It was Gaston who invented the term "coffin nails."

Next to Carry Nation, who entered a Wichita, Kan., saloon

with a hatchet in January, 1901, and within minutes

destroyed the place, Gaston was the leading female reformer

in America.

Lucy Page Gaston  Calvin Coolidge, who succeeded Harding in 1924, didn't like

Prohibition because "any law that inspires disrespect for

other laws -- the good laws -- is a bad law." Banning liquor

helped fund organized crime. People with good motives used

wrong tactics in an attempt better social conditions and,

instead, made things worse. Adolph Busch, the brewer, wrote

President Coolidge: "An unpopular statutory control of

individual habits can never be substituted for voluntary

temperance, individual self-restraint and reasonable statutory

regulation. The law should be written in terms of temperance

and reasonable regulation; then the evils of the present

system would disappear."

Calvin Coolidge, who succeeded Harding in 1924, didn't like

Prohibition because "any law that inspires disrespect for

other laws -- the good laws -- is a bad law." Banning liquor

helped fund organized crime. People with good motives used

wrong tactics in an attempt better social conditions and,

instead, made things worse. Adolph Busch, the brewer, wrote

President Coolidge: "An unpopular statutory control of

individual habits can never be substituted for voluntary

temperance, individual self-restraint and reasonable statutory

regulation. The law should be written in terms of temperance

and reasonable regulation; then the evils of the present

system would disappear."