|

|

Jewish World Review / May 21, 1998 / 25 Iyar, 5758

William Pfaff

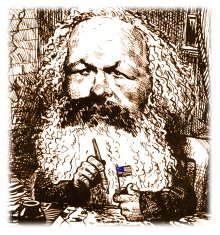

PARIS -- Marx and Engels' Communist Manifesto, which is

150 years old this year, did not change the world for which it

was written. The manifesto proved nonsense as forecast of

the workings of a supposed dialectic of history, and it was

disastrous in its political consequences. It produced the

utopian totalitarianism of Lenin and Stalin, with systematic

and destructive attack upon every rival conception of reform.

The leaders inspired by Marx and Engels understood that

while it was profitable to them to preach anti-capitalism,

anti-imperialism and anti-fascism, the real threat to them

came from the social democratic, Christian democratic and

liberal reform movements of 19th- and 20th-century Europe

and America.

However, the ideological identity that Marx and Engels had

given to communism, as the sole historical alternative to

capitalism, meant that the capitalists themselves came to

believe this, and when the Communist movement failed, 80

years after it had come to power in Russia, this seemed an

unqualified validation of capitalism.

On the other hand, virtually everyone today would

acknowledge that Marx and Engels were prophetic analysts of

capitalism. Their account of a restless, innovative,

internationalist industrial system, constantly destroying and

recreating itself, is actually a better description of today's

globalized free-market capitalism than of the capitalism of

1848, when they wrote.

Their description of a conscienceless and predatory system

finds echo among globalism's critics today, even those who

believe, with Margaret Thatcher, that there is no alternative

to the system which now prevails among the industrialized

nations and in a large part of the non-Western world.

Many concerned for the social and human devastation that

globalization can produce, and its indifference or hostility to

ethical and social considerations, have nonetheless concluded

that the technological, economic and political forces behind it

are irresistible.

Most voters in the industrial nations undoubtedly take for

granted the system in which they live. The winners rejoice in

its opportunities. The losers may resent their loss of security,

and the market's destruction of familiar social structures and

values, but find it hard to think that anything can be done to

change what is happening.

A consequence of Marxism's collapse has been that it has

seemed to rule out critiques of modern capitalism as

irrelevant and make proposals to reform it seem futile or

utopian. A basic division of opinion exists today between

those who think that a choice of society does still exist, and

those who believe that no choices remain: that in the famous

formulation of Francis Fukayama (and in a sense he did not

intend, but which was implicit in what he wrote), history has

ended.

This division exists inside countries, but also divides certain

nations from others, notably in setting what can be called the

Atlantic countries -- the United States, United Kingdom, the

Netherlands and certain others -- from those where voters are

prepared to believe that contemporary capitalism can or

should be changed, or at least that it can be reconciled with

the model of social capitalism, or welfare capitalism, which

emerged in Western Europe and Scandinavia after World

War II.

The Germans and French are leaders of the latter group. The

next German national election, in September, will turn in part

on social and welfare issues. In France these issues were

responsible for a devastating and unexpected defeat of the

conservative government in parliamentary elections a year

ago.

The French Communism newspaper L'Humanite recently

commissioned a national poll in France on attitudes toward

capitalism. Asked whether they felt enthusiasm about

capitalism, or hope, indifference, fear or rebellion, 22 percent

said enthusiasm or hope, and 53 percent said fear or

rebellion. This was a cross-section of the entire population.

The 10 values that the French respondents to this poll

associated with capitalism were, in order of importance,

technological innovation, egoism, competitivity, creation of

riches, unequal opportunity, progress, social exclusion,

freedom of expression, devaluation of work and insecurity.

But people believe that the system can be changed. Ninety

percent of those polled in France said they wanted change:

13 percent radical change, 33 percent ``change in depth,'' 44

percent improvements in the system. Only 5 percent were

content with the economic system as it is.

A belief in the possibility of change characterizes the German

Social Democrats (and Greens), who are now considered

likely to win power in September. The Socialist-led

government in France is committed to reconciling the social

commitments already made in France with economic reform.

It is, of course, one thing to want change and another thing to

succeed with it. The interesting thing is that the two countries

which will dominate ``Euroland'' -- the new European

monetary bloc that comes into existence next January -- resist

the free-market consensus on the irreconcilability of a

successful economy with a welfare state. That is as significant

a fact as the emergence of European monetary union

The Communist mainfesto, at 150, prophesied the

shape of today's capitalism

The Communist mainfesto, at 150, prophesied the

shape of today's capitalism

5/19/98: Globalized capitalism is more significant than

nuclear weapons

5/13/98:

Negotiating in reality, not

wishfulness

5/7/98:

Things can only get better

and better!

5/5/98:

Racial, ethnic, national barriers disappearing

5/5/98:

Racial, ethnic, national barriers disappearing

4/21/98: A terrifying synthesis of forces spawned Pol Pot's regime

4/19/98: Russian-German-French structure of consultation is good development

4/16/98: Violence in society comes from the top as well as the bottom

4/13/98: Clinton's foreign policy does have a sunny side, too

4/8/98: Public interest must control marketplace

4/5/98: Great crimes don't require great villians

3/29/98: Authority rests on a moral position, and requires consent

3/29/98:Signs of hope in troubled Russia

3/25/98: National Front amassing power

3/23/98: NATO's expansion contradicts other American policies

3/18/98: The New Yorker sought money, but lost it

3/16/98: America's 'strategy of tension' in Italy

3/13/98: Slobodan Milosevic may have started something that can't be stopped