|

|

William Pfaff

Great crimes don't require great villians

Great crimes don't require great villians

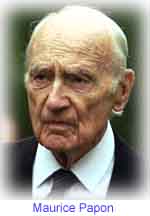

PARIS -- The verdict in France's trial of Maurice Papon for complicity in crimes against humanity -- "guilty," but with a sentence of only ten years -- was apologetic rather than Solomonic. It followed from the realization by the jury and by much of the public that they had the wrong man.

They wanted a man of recognizable evil, defiant in his crimes or contemptible in his evasions. What they got was an arrogant old man whose crime was to have been a careerist.

While the jury convicted him of the charge that had been

brought, they did not impose the  full possible sentence, life

imprisonment, nor even the sentence the prosecutor

demanded, 20 years in prison.

full possible sentence, life

imprisonment, nor even the sentence the prosecutor

demanded, 20 years in prison.

They gave him half that -- although the distinction is probably without a difference, since the convicted is 87 and his heart is bad. He will not go to prison until the case has been appealed, which means that he may never serve the sentence.

The trial was meant to educate the young about Vichy and France's implication in the deportation of Jews to the death camps. It may be questioned whether the education was necessary. The French by now know all about Vichy. The lesson actually taught was how complicated history is.

Maurice Papon's principal defender asked how he could be the accomplice of a genocide he did not know was being committed. The defendant himself asked how the prosecution could demand a penalty of only 20 years when it held him responsible for a crime against humanity. "Can there be 10, 15, 30, or 60 percent of a crime against humanity? ... It is all or nothing. Either I am guilty or innocent."

Knowledge of genocide thus became an important but misleading issue in the trial. Some witnesses insisted that Mr. Papon had to have known what would happen to the deported Jews -- or known enough.

Some of his contemporaries, who were in the resistance, testified that they had not known, and that the Gaullist authorities in London did not know. On the evidence of its conduct, the American embassy to Vichy did not know. (The United States recognized the Vichy regime as France's legitimate government from the start, and did not formally renounce relations until January 1944.)

The most telling evidence about not knowing was quoted from the late Raymond Aron, one of the most distinguished modern political thinkers, himself a Jew, who was in London with de Gaulle.

He said that, at the time, extermination by the Germans of a whole category of humanity was unimaginable. Simply because it could not be imagined, no one imagined it -- not until the Allied armies began to overrun the camps in 1945.

Mr. Papon did not have to know about death camps to know that something terrible was happening. He knew that these men, women, and children were selected on ``racial'' grounds to be taken away toward something unknown and certainly bad. What was his justification for continuing to take part in Vichy's collaboration with the Nazis, when what he was doing resulted in self-evident evil?

He claimed to have been a resister. He said that he was able to do more for the Nazis' victims, and for the resistance, by staying in office, than he could have accomplished by leaving. Some witnesses agreed; some objected.

When the war was over and the Free French took control, he was summarily assessed to be fit to remain in the civil service. From that point, he never looked back, except once. Many years later, when he had become a candidate for ministerial office, but rumors of collaboration persisted, he submitted himself to an informal "court of honor" of resistance leaders and was passed, but rather grudgingly.

At his trial he claimed to be the victim of a conspiracy, dominated by the Communists. He had been head of the Paris police late in the war in Algeria, when Paris experienced terrorism and riots protesting French policy. He said the Communists have hated him ever since because as head of the police he was their most effective enemy.

He also implied that Jewish organizations are part of the conspiracy, making a symbol of him, so that in Bordeaux over the past six months it was not the man who was being tried but "the myth, elaborated over many years, and by expert hands!"

It nonetheless was one of the lawyers for the civil parties associated with the prosecution, Arno Klarsfeld, himself a Jew, who surprised the court in his summing-up by proposing the ten-year sentence, saying that Mr. Papon did not deserve more.

This was an implicit acknowledgement that they had the wrong man. They had an ambitious functionary. Mr. Papon administered a despicable collaboration with the Nazis, implementing a self-evidently evil policy of arresting and deporting people guilty of no crimes, to a fate which, whatever it was, would certainly be harsh.

He demonstrated the same amoral detachment and

bureaucratic rigor which all across Europe in the 1940s made

the organization and execution of great crimes possible. That

was the crime proven here, and the lesson taught. It is a crime

that continues to be committed today. The great crimes do

not require great villains. They are committed by those who

do not

3/29/98: Authority rests on a moral position, and requires consent

3/29/98:Signs of hope in troubled Russia

3/25/98: National Front amassing power

3/23/98: NATO's expansion contradicts other American policies

3/18/98: The New Yorker sought money, but lost it

3/16/98: America's 'strategy of tension' in Italy

3/13/98: Slobodan Milosevic may have started something that can't be stopped