Filed last year by the state of Alabama and Rep. Mo Brooks, R-Ala., against the Commerce Department and the Census Bureau, it argues that the current system of apportioning congressional seats gives an unfair electoral advantage to states with more undocumented immigrants. It says immigrants should not be counted for apportionment or federal funding if they are not in the United States legally, even if they do fill out the decennial survey. A hearing is scheduled for Sept. 6.

The concept is a radical shift from anything the country has done in the past. But it is in line with public and private statements from some government officials since Trump took office. It comes as the administration has said it will collect citizenship information from administrative records, which could make it easier for the government to estimate the number of undocumented immigrants in the future.

Experts on the Constitution and the census say the Alabama suit is unlikely to succeed, and note that even if it did, it could be impossible to implement the new system in time to affect the 2020 count. But some see it as a strategy to move the needle on the national debate.

"There are no merits to the case," said Thomas Wolf, counsel with the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law. "It could be an attempt to normalize a position in the court of public opinion that they can't win in a court of law . . . That's why it's important to make clear how abnormal, un-American and aberrant these ways of doing things are."

Some also question whether the Justice Department will mount a robust defense, especially in light of comments last month by Attorney General William Barr that seemed to suggest the case could succeed.

A federal judge has also expressed doubt over the government's commitment to defending it, citing this in his decision last year to allow advocates and jurisdictions to join the suit as defendants. And this week, 16 states requested to intervene, referring to Barr's comments in their request.

Both the Justice and Commerce departments declined to comment for this story.

Alabama's proposal would overturn a system that has remained largely intact since the decennial count began in 1790. The Fourteenth Amendment, enacted after the Civil War, mandates that representatives be apportioned "counting the whole number of persons in each State" (the Constitution's original census clause contained similar language but distinguished between free people and slaves, who counted as three-fifths of a person).

According to federal law, the commerce secretary, who is in charge of the Census Bureau, must provide decennial census numbers by the end of the census year - in this case 2020 - to the president, who then reports it to Congress. Apportionment of the country's 435 House seats and electoral votes is determined by those numbers.

Based on current population estimates, Alabama is projected to lose one congressional seat and one electoral vote. In the scenario proposed by the lawsuit, it would retain its current number of representatives, while states with more undocumented immigrants would lose more seats.

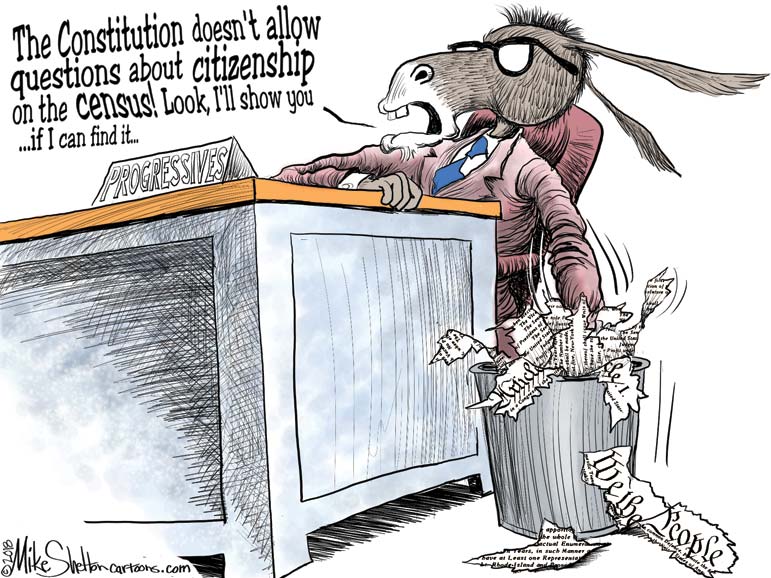

The case hinges on parsing out what the Founders meant by the word "person" or the word "in." It contends that "persons in each State" does not refer to undocumented immigrants, arguing that the phrase was "understood at both the Founding and in the Reconstruction era to be restricted to aliens who have been lawfully admitted to the body politic." It argues that "properly" interpreting the laws governing the census and apportionment would mean counting only "the total of legally present resident population of the United States."

It is not the first time these questions have been raised; such debates took place during the drafting of the Constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment, said Terri Ann Lowenthal, a former staff director of the House census oversight subcommittee.

"Congress on multiple occasions . . . has specifically debated whether to change the language from 'persons' to 'citizens' or 'voters,'" she said. "Congress was well aware that retaining the word 'persons' suggested a universal inclusion of all persons in the United States. They specifically rejected narrowing the universe of people in determining representation."

More recently, the Supreme Court ruled in 2016 that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment allows states to use total population, not just total voting-eligible population, to draw legislative districts.

Past litigation has left little room for debate, said Justin Levitt, an election law professor at Loyola Law School who was a deputy assistant attorney general in the Department of Justice's Civil Rights Division from 2015 to 2017.

"You count everybody," he said. "You count persons in each state, and that is something that we eventually fought a civil war over, as we used to have caveats about that. Everybody gets represented. Literally everybody."

The concept of legal residency didn't exist at the time the Constitution was framed, Levitt said. "There was no restriction at the time to being here with the permission of the government." The lawsuit, he said, is simply "an attempt to further a conversation" on who's a proper part of what it means to be America."

But in an email to The Washington Post, Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall said the word "inhabitant" indicates "a level of permanence and commitment to a political community . . . Thus, a resident of another State or country who is simply passing through a State on the census date is not counted as being part of that State. Nor should someone whose ties to the State are inherently tenuous, as in the case of people who are present in the country (and that State) illegally."

The citizenship question would not have asked about people's legal status, but challenges in court claimed it was an attempt to exclude immigrants and minorities, and the Democratic-voting jurisdictions in which they tend to live, from political representation and funding.

Discussions about changing apportionment criteria are not new. During litigation over the citizenship question, files from the hard drives of deceased Republican redistricting strategist Thomas Hofeller included a 2015 study of his showing that drawing political maps based only on citizens of voting age rather than a state's total population, as most of the nation now does, would give Republicans and white people an electoral advantage. Emails showed Hofeller had discussed the citizenship question with officials in the Trump administration and the Census Bureau.

And in a 2017 email urging Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross to add a citizenship question, then-Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach said the lack of such a question "leads to the problem that aliens who do not actually 'reside' in the United States are still counted for congressional reapportionment purposes." Trump, too, when asked last month about the citizenship question, said, "Number one, you need it for Congress."

The administration's robust pursuit of the citizenship question ended only after the Supreme Court blocked it, saying the government had provided a "contrived" reason for wanting the information.

Because of how doggedly the government pushed for the question, some advocates said they feared the Justice Department will not defend the Alabama suit wholeheartedly. In light of that, a group of Hispanic voters and a civil rights organization, and a group of jurisdictions in California and Washington state joined the government as defendants in the suit shortly after it was filed.

"In this case it was a particular concern that the Trump administration could not be trusted to put up a vigorous defense," said Thomas A. Saenz, president and general counsel of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which is representing some of the intervenors.

The judge seemed to concur. In his decision to allow the intervention, U.S. District Judge R. David Proctor called the government's motion to dismiss "halfhearted" and said he was concerned that it had overlooked a key argument. "Allowing intervention will increase the prospect that the court will be more fully informed of the best arguments that support Defendants' position," he wrote.

On Monday, a coalition of 16 states, nine cities and counties, and the U.S. Conference of Mayors also requested to join as intervenors, arguing that under Alabama's proposal they would lose seats and electoral votes. The city of Atlanta and Arlington County in Virginia on Monday requested to join the existing group of intervening jurisdictions.

The coalition, led by New York Attorney General Letitia James, said in its filing that it was concerned about the Justice Department's commitment to defending the case particularly after remarks last month by Barr in which he seemed to refer to the Alabama case.

Standing beside Trump in the Rose Garden on July 11, the day the administration said it would drop its quest to add the citizenship question and would instead seek data on citizenship status through administrative records, Barr said that information would be used "for countless purposes . . . For example, there is a current dispute over whether illegal aliens can be included for apportionment purposes. Depending on the resolution of that dispute, this data may be relevant to those considerations."

Levitt called the comment "really concerning."

"It's exceedingly odd to hear the attorney general lifting up an attack on the federal government's position," he said. "It's not the job the attorney general was supposedly hired to do."

Lowenthal agreed, saying Barr's suggestion "that this administration may not view that constitutional requirement as settled is unusual and troubling."

Even if the Alabama suit were to succeed, it is unclear whether the bureau could use administrative records to get accurate information on the number of undocumented immigrants by state in time for Congress to use it for reapportionment.

The Census Bureau did not respond to a question from The Post about whether it planned to provide such information to Congress. In response to such a question from Rep. Ayanna Pressley, D-Mass., Census Bureau Director Steven Dillingham said earlier this month that the bureau does not comment on ongoing litigation, an apparent reference to the Alabama case.

Former Census Bureau director John Thompson called that response "strange," noting that pending lawsuits had never stopped him from discussing census methodology when he was director. "It raises a lot of suspicion in my mind that something's going on that they can't talk about," he said. "I think the Department of Commerce is not letting them talk about it, or the White House, or both."

Robert Groves, provost at Georgetown University and a former Census Bureau director, said attempting to use administrative records to exclude undocumented immigrants from apportionment would be technically difficult, if not impossible.

"The problem if you mix administrative records from multiple agencies is it's often ambiguous whether you have a duplicate," he said.

He added that, because estimates of undocumented people are made using citizenship data, the timing of the records might not match, since the records may be from different points in time.

"Administrative records are not designed to ask people, 'What is your citizenship status as of April 1?' " (Census numbers are based on that date.)

Challenges such as Alabama's are part of a historical pattern, observers said.

"At times when immigration has been an issue of significant national dialogue and, in some cases, a source of anxiety that could be stoked by elected leaders, the implications of immigration levels for the allocation of political representation based on the census often became wrapped up in that anxiety," Lowenthal said. "We are at that point again in our history."

Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author