My daughter's age 5 wellness check, too.

Amid a global pandemic, determining what medical care is indispensable for public health is critical to conserving supplies and protecting health care workers.

For those of us who are healthy, preventive care — a crucial part of overall public health in normal circumstances — and medically non-urgent procedures are expendable right now.

So I'm baffled by the debate raging over whether elective abortions, which neither save nor prolong life in cases involving healthy women, should be considered essential.

The obvious answer should be no, they are not.

That's what the state of Texas determined, as did Ohio, Alabama, Iowa and Oklahoma, until federal judges intervened. In Texas, at least for now, the state's temporary ban on medically unnecessary abortions will stand.

In a predictable sequence of events, pro-life governors, perhaps seeing an opportunity, moved to restrict abortions; abortion-rights groups challenged them, arguing that even during a worldwide crisis, one of our top national priorities should be ensuring access to on-demand abortion services.

How banal.

The whole ordeal underscores a problem with the fact that our courts, not democratically elected state governments, decide where a woman's right to be not pregnant ends and the right of the life within her to exist begins.

It also forces us to consider, in a very unequivocal way, whether abortion is health care at all.

It's not.

By definition, health care is supposed to restore or maintain health; to treat or prevent disease or injury.

Pregnancy is not an illness or a disease. On the contrary, it sometimes results when our bodies are functioning as they should.

That remains true whether the resulting baby is wanted or unwanted.

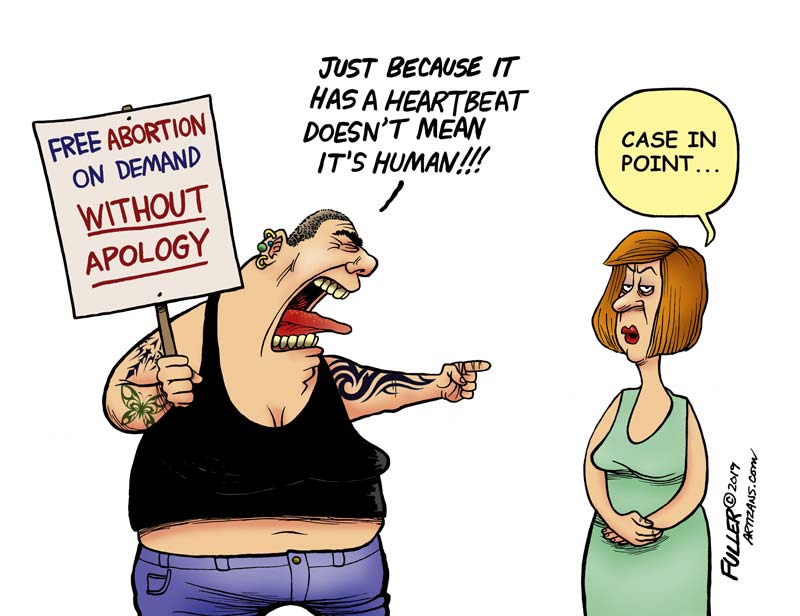

Calling abortion health care, let alone "essential health care", requires what the National Review's Alexandra DeSanctis calls "a radical redefinition of health and medicine."

What an inopportune time to be redefining medical care, while thousands of health care professionals the world over are working around the clock to fulfill the Hippocratic oath in the most trying of circumstances. Some are being forced to make impossible decisions about who receives care when resources are scarce, about who lives and who dies.

It's hard to square that with those who are promoting procedures that intentionally leave one of two patients dead every time.

Some have argued that the effort to conserve personal protective equipment for medical workers is actually better served by abortions because women carrying unwanted babies will need prenatal care and that will siphon away medical resources anyway.

That's morbid — and wrong. There is currently no recommendation for obstetricians and gynecologists to wear protective equipment during outpatient visits involving persons without COVID-19 or its symptoms. Telemedicine appointments are possible for some prenatal visits.

And it's odd to quibble over medical equipment being used to preserve and protect life given the alternative.

Others have worried of increases in cases of rape or incest, given an uptick of domestic abuse during state-mandated quarantines. But according to the pro-choice Guttmacher Institute, only 1% of women seeking abortion do so in cases of rape; less than 1% of abortions are sought in cases of incest. Those numbers are unlikely to change dramatically. If they do, states can broaden exceptions.

I'm sensitive to the fears that our current economic collapse will make children difficult for some to afford. But "abortion to avoid economic hardship" is the refrain of abortion proponents in healthy economic times. And an unprecedented global crisis doesn't buttress the contention that the unborn should be extinguished until we're better able to afford them. We need the hope of new life more than ever.

Of all the things that could change during this pandemic, how we view life's inherent value should be one of them. That is the argument for protecting the elderly and the immunocompromised. Their lives matter.

Especially now, why shouldn't that same reasoning apply to the unborn?

Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Cynthia M. Allen

Fort Worth Star-Telegram

(TNS)

Cynthia M. Allen is a columnist for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author