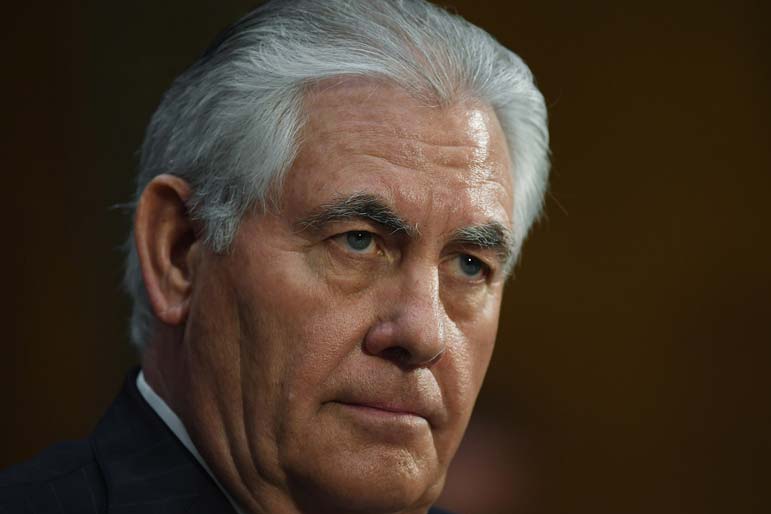

Rex Tillerson, the U.S. secretary of state. Matt McClain for The Washington Post

Rex Tillerson, the U.S. secretary of state. Matt McClain for The Washington Post

"Why should U.S. taxpayers be interested in Ukraine?" That was the question that Rex Tillerson, the U.S. secretary of state, was heard to ask at a meeting of the Group of Seven foreign ministers, America's closest allies, a day before his visit to Moscow last this week. We don't know what he meant by that question, or in what context it was asked. When queried, the State Department replied that it was a "rhetorical device," seeking neither to defend nor retract it.

If Tillerson were a different person and this were a different historical moment, we could forget about this odd dropped comment and move on. But Tillerson has an unusual background for a secretary of state. Unlike everyone who has held the job for at least the past century, he has no experience in diplomacy, politics or the military; instead he has spent his life extracting oil and selling it for profit. At that he was successful.

But no one knows whether he can change his value system to focus instead on the very different task of selling something intangible - American values - to maximize something even more intangible: American influence.

The switch is harder than it seems: Values and influence cannot be measured like money. They cannot be achieved through cost-cutting or efficiency; they cannot be promoted using the tactics of corporate PR. On his first trip to Asia, for example, Tillerson refused to take the usual contingent of journalists (who have always paid their own way) on the grounds that if he took fewer people he could use a smaller plane and return faster.

If he were still a chief executive, that might have been a great decision. For the secretary of state it was an embarrassing mistake. Authoritarians around the world saw further evidence that the Trump administration intends to undermine journalism; Americans learned less than they should have about a visit that was covered mainly by foreigners.

Tillerson's question, rhetorical or otherwise, therefore deserves a response. For the answer is yes: U.S. taxpayers should be interested in Ukraine. But not necessarily for reasons that would make sense to an oil company's CEO.

Why? It's an explanation that cannot be boiled down to bullet points or a chart, or even reflected in numbers at all. I'm not even sure it can be done in a few paragraphs, but here goes. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea in 2014 were an open attack on the principle of border security in Europe.

The principle of border security, in turn, is what turned Europe, once a continent wracked by bloody conflicts, into a safe and peaceful trading alliance in the second half of the 20th century. Europe's collective decision to abandon aggressive nationalism, open its internal borders and drop its territorial ambitions made Europe rich, as well as peaceful.

It also made the United States rich, as well as powerful. U.S. companies do billions of dollars of business in Europe; U.S. leaders have long been able to count on European support all over the world, in matters economic, political, scientific and more. It's not a perfect alliance but it is an unusual alliance, one that is held together by shared values as well as common interests. If Ukraine, a country of about 43 million people, were permanently affiliated with Europe, it too might become part of this zone of peace, trade and commerce.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, an aggressive, emboldened Russia increasingly threatens European security and prosperity, as well as Europe's alliance with the United States. Russia supports anti-American, anti-NATO and indeed anti-democratic political candidates all across the continent; Russia seeks business and political allies who will help promote its companies and turn a blind eye to its corrupt practices. Over the long term, these policies threaten U.S. business interests and U.S. political interests all across the continent and around the world.

But I must concede: There is no calculation, no balance sheet that can prove any of this. There is nothing that would appeal to a CEO or his shareholders. Whatever we have "invested" in Ukraine - loans, via the International Monetary Fund, or aid - will not show an immediate profit. To see the value of a secure, pro-Western Ukraine, you have to see the value of an alliance going back 70 years. And to preserve this alliance, you have to advocate it, work on it, invest time and maybe even money in it, too.

Tillerson's boss isn't going to be an advocate for America's alliances. Will he? It would help if he could start by understanding that their stability, not their value for money, are the most important measure of success in his job.

Anne Applebaum is a Washington Post columnist. She is also the Director of the Global Transitions Program at the Legatum Institute in London.

Previously:

• 04/16/17 Ground zero for Russian interference

• 01/30/17 May's 'global Britain' is doomed

• 12/21/16 I was a victim of a Russian smear campaign. I understand the power of fake news

• 12/14/16 Russia's next election operation: Germany

• 10/31/16 Why all the talk of World War III?

• 10/23/16 The fate of the American order in the Pacific

• 10/16/16 Is Europe building a 'liberal wave'?

• 08/15/16 The strongman ties that bind

• 07/26/16 Connecting the dots: How Russia benefits from the DNC email leak

• 07/25/16 Putin's wager on Trump is paying off already

• 06/22/16 What started as an argument over tax and spending morphs into a debate about immigration and the preservation of Englishness in a dangerous world

• 05/23/16 A world without facts

• 05/09/16 Russia seeking to undermine Western institutions --- with rebooted tactics

• 04/27/16 Trump's campaign brings Eastern Europe's political 'tactics' to the US

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author