Suppose, however, you spent last summer applauding the riots, or dissembling about them, or dismissing them. In that case, to deplore last week's violence credibly is not so simple. If you demand that your political adversaries adhere to a principle, but exempt people whose cause you endorse from having to comply, then that preference you enjoy boasting about is not really a principle. It is not a standard of conduct applicable to all, in other words, but just another rhetorical device used for political combat.

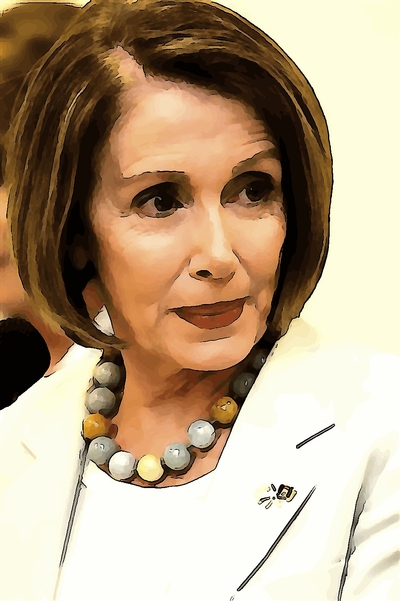

If you're Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, for example, a question in July about mobs toppling statues in public spaces elicited not a denunciation but a koan: "People will do what they do." Indeed, people will do what they do. Some people, for example, will break into the Capitol and occupy the Speaker's office. But limiting oneself to the serene observation that this is what they do would constitute a grave failure to repudiate an offense against law, order, and democracy.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, who won a Pulitzer Prize for creating the New York Times's "1619 Project," also expressed equanimity and even pride regarding last year's unrest. "It would be an honor," she said, if the burning police stations and looted stores came to be described as the "1619 Riots." In any case, "Destroying property, which can be replaced, is not violence." Hannah-Jones went on to explain, "Any reasonable person would say we shouldn't be destroying other people's property, but these are not reasonable times." Reasonable people also say that mobs should not overrun the seat of government or be gratified if someone calls that assault the "1776 Riots." But if declaring "these are not reasonable times" changes everything, then the loophole devours the rule, or even the idea of having rules.

When protesters surrounded a Seattle police station, forcing officers to evacuate it, and declared the adjacent area an "autonomous zone," mayor Jenny Durkan was reassuring: "Don't be so afraid of democracy." Civic and political leaders in Philadelphia were equally non-judgmental about the shattered glass and boarded stores on their streets. "I don't think we need to be parsing whether there needs to be looting," said one city council member. Rioting was "understandable but regrettable," Jesse Jackson said in June, a quasi-criticism no one would think to apply to the Capitol Hill mob.

In the wake of last week's riot, formulations like these have become deeply embarrassing. What is to be done? One option would be for the people who put them forward, and their many political allies, to admit the obvious: since riots are bad — utterly, always, and everywhere — justifying them, or praising them with faint damns, is also colossally irresponsible. The people who set last summer's fires, looted stores, or assaulted motorists and pedestrians should be condemned, and the people who made excuses for their behavior should be ashamed. Reader, you are borne through life with a sunnier view of human nature than I if you are dismayed that no such apologies or retractions have yet been offered.

A different response to conservatives who have started 2021 by rudely calling attention to the riot apologists of 2020 is: Shut Up. A more sophisticated way to say Shut Up is to accuse conservatives whose memories go back more than three months of engaging in "whataboutism." This is the position of University of Wisconsin political scientist Kenneth R. Mayer, who believes that any public official "who does not immediately and unequivocally condemn [the Capitol riot] without using the words ‘I understand,' ‘but,' or any variant suggesting that the rioters had a point but went too far, should forfeit their right to hold public office." Furthermore, "any elected official who engages in ‘whataboutism,' or complains that the other side does it too, should leave next."

Similarly, "Whataboutism is the last refuge for someone who can't admit they're wrong," says journalist Tod Perry, who demands that we "stop equating Trump's Capitol insurrection to Black Lives Matter protests." The Atlantic's David A. Graham also declares that conservatives' "complaints about double standards are mostly whataboutism and don't carry much weight." After last week's rioters had been expelled from the Capitol Building, a Republican congressman noted with approval that "at least for one day I didn't hear my Democrat colleagues calling to defund the police." Such responses, Jeremy W. Peters of the New York Times scolded, were "full of whataboutism, misdirection and denial."

What exactly is this whataboutism which conservatives have committed so flagrantly? The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as, "The practice of responding to an accusation or difficult question by making a counter-accusation or raising a different issue." Also, "the practice of raising a supposedly analogous issue in response to a perceived hypocrisy or inconsistency." The term came into use in the twentieth century, often to describe a rhetorical gambit wherein any criticism or question about the Soviet Union's human rights violations elicited an objection about the West's transgressions. In 2001, my Murray Hill neighbor was the comedian "Professor" Irwin Corey, then an 87-year-old unreconstructed Marxist. On the afternoon of 9/11, after both towers of the World Trade Center had collapsed, I walked past Corey, outside his townhouse in mid-harangue: "Well, what about what our country did to the Indians?"

Whataboutism offends against the good-faith pursuit of truth and clarity by evading a legitimate question and dragging in irrelevancies. Whether or not 9/11 was evil has nothing to do with the Trail of Tears. Nor am I obliged to accede to the stipulation that I must first denounce whatever historical crime you happen to mention before you consent to take note of the shocking atrocity that took place downtown a few hours ago.

To nail conservatives for whataboutist responses to the Capitol riot requires demonstrating conduct like Irwin Corey's, or that of some Soviet apparatchik responding to a question about the Gulag with one about Jim Crow. When Senator Marco Rubio and commentator Ben Shapiro, for example, complain about media double standards — lenient for BLM, severe for MAGA — Graham dismisses the "superficial parallels" and Peters the "false equivalencies." We should, of course, reject false equivalencies — because they're false. But to complain about false equivalencies necessarily implies that there are true equivalencies.

It also strongly implies that different cases, though not identical, can be comparable in ways that fairly illuminate some underlying question. If whataboutism entails "raising a supposedly analogous issue in response to a perceived hypocrisy or inconsistency," then raising plausibly analogous issues in response to a demonstrable hypocrisy or inconsistency does not qualify as whataboutism. Whether issue X is or isn't analogous to issue Y, whether inconsistency Z is apparent or real, irrelevant, or germane — these disagreements become elements of any fair debate. And because it is legitimate for one side to raise such questions, it is illegitimate for the other side to use facile, tendentious accusations of whataboutism to rule them out of order. The point of that tactic is not to win a debate but stifle it.

The briefs filed by the whataboutism prosecutors fail to satisfy any reasonable burden of proof that the many rationalizations of the BLM riots have no place whatsoever in any discussion of the MAGA riot. To a considerable degree, they simply reiterate the regrettable-but-understandable framing from last summer: the BLM riots were not justified, but neither were they really unjustified. "Violence against businesses and police stations is wrong," writes Graham, but "Black Lives Matter demonstrators were protesting about a real problem." Perry does the same thing: "Property destruction and violence should never be tolerated no matter who's involved. But what we break and why we break it is important."

Both contrast BLM's genuine and urgent grievances with the spurious ones about vote fraud that fueled the MAGA riot. Even if one stipulates the point, however, the problem with saying "but these are not reasonable times," as Hannah-Jones does, remains. Because there is no injustice-validation tribunal to predetermine whose complaints merit suspending the ordinary strictures against rioting, the question is crowdsourced. People will decide for themselves about taking it to the streets. And once they do, there is no guarantee that MAGA will be unique in abusing this prerogative. Looters tore apart Chicago's North Michigan Avenue shopping district in August, resulting in 13 police officers being injured and the arrest of more than 100 people, because of rumors spread on social media that police had shot an unarmed 15-year-old on the South Side. What actually occurred was that a 20-year-old convicted felon, subsequently charged with two counts of attempted first-degree murder, was wounded after he fired on police officers.

In any case, debating which rioters are more aggrieved only compounds the underlying problem: contending that any grievance qualifies the otherwise categorical rejection of rioting puts us on a slippery slope to a dangerous place. Perry inadvertently conveys how dangerous by claiming that the BLM riots were not really all that riotous. "The Black Lives Matter protests had no intention of being destructive," he says, citing a study that determined that "93% of the 7,750 demonstrations . . . were peaceful."

In other words, 7 percent — some 543 demonstrations — were not peaceful. Because the report, by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, examined an 89-day period from May 26 to August 22, 2020, that works out to an average of more than six violent events per day during last summer's mostly peaceful BLM demonstrations. It appears that the property damage from these austere, placid gatherings totaled between $1 billion and $2 billion, and that some two dozen people were killed amid the prevailing tranquility.

Unlike Graham's and Perry's granular anti-whataboutist arguments, Jeremy Peters makes his case from 30,000 feet. "Trump sympathizers were quick to try to shift the focus from the destructive scene in Washington," he writes, "and revive months-old stories about the fires and looting." It is strange, in general, to assert that riots that occurred whole, entire months ago — gosh, who can even count how many? — are self-evidently unrelated to a more recent riot. It is a particularly odd dismissal of the hazy, archaic past coming from a reporter for the New York Times, which mentioned the 1955 murder of Emmett Till in 82 different stories over the course of 2020.

In May 2018 Times contributor Lindy West defended the cancellation of Roseanne Barr's television show, a skirmish in the "cancel culture" wars. It is "our collective responsibility" to fight racism and hate, West wrote, "and right now cultural power is all we have." West did not expand on her use of the first-person plural, but it was pretty clear that if you had to ask, you weren't part of it. The "cultural power" that "we have" is a strong clue. It's the power exercised by media and academic institutions, in particular, opinion leaders shaping the national conversation to determine which stories get told, which voices heard, which arguments taken seriously.

The whataboutism indictments mean that we, who wield this cultural power, can deliver crazy and dangerous pronouncements during one historical circumstance, and then a few months later use that power to decree that the earlier pronouncements are irrelevant to whatever points we're making today. Cultural power means never having to say you're sorry and never having to feel you're constrained. Go ahead: take outrageous positions or issue preposterous formulations today, confident that if they make you or us look bad in the future, we, the culturally powerful, will join together to manufacture a consensus that even alluding to those embarrassments is now impermissible. It will be as if they never happened. Kant's categorical imperative about committing or defending only those actions you would uphold as universal principles is ground down to a speed bump. Cultural power demolishes universality with situational assertions of relativity: That was then; this is now. If some annoying troll complains about our inconsistency or hypocrisy, we'll respond with accusations of whataboutism, an update of the credo voiced by Eric Stratton in Animal House: You f---ed up. You took us seriously.

At the same time, conservatives do not really have the option of not taking the culturally powerful seriously, precisely because they are powerful. And as of 2021, they are far more powerful, adding political power to the cultural kind with Democrats in charge of the presidency and both houses of Congress. This power is augmented by economic power, demonstrated in Amazon, Apple, and Google's shock-and-awe kneecapping of the social-media startup Parler. The culturally powerful have graduated from gatekeeping the national conversation to interdicting conservatives' private conversations. As the fictional woke sage, Titania McGrath, warned on Twitter (which has banned "her" in the past): "The wonderful thing about being on the right side of history is that we can encourage big tech censorship without any fear that it might one day be used against us."

Coming on top of sweeping accusations of whataboutism, the destruction of Parler is an ominous escalation. The culturally powerful appear less and less culturally responsible, less inhibited by a sense of concern for the whole polity, by any notion that viewpoints they do not share are entitled to respect — or even oxygen. Unless a new president who has promised to heal wounds is not just a front man for a nomenklatura that intends to settle scores, de-escalation is imperative. It is time to entreat the culturally powerful to assess their obligations carefully and wield their powers scrupulously. To them, I say: What about it?

(COMMENT, BELOW)

William Voegeli is a senior editor of the Claremont Review of Books and author of Never Enough: America's Limitless Welfare State and The Pity Party: A Mean-Spirited Diatribe Against Liberal Compassion.

Previously:

• 11/09/20 With enemies like today's progressives, conservatives don't need many friends

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author