At Above the Law, the legal news website I founded in 2006, my colleague Elie Mystal and I were covering the developments closely. In the reader comments, we noticed persistent predictions bubbling up of layoffs at leading law firm Latham & Watkins. These comments led us to investigate further, working our sources at Latham. Before Latham eventually announced its massive, record-setting layoffs, we broke the story - and we owed the scoop, one of our biggest ever, to our comments section.

Reader comments in the early days of Above the Law were a treasure trove of information, insight and humor, advancing our mission of bringing greater transparency to an often opaque profession. Comments were wildly popular; some readers came specifically to read them, and some commenters became Internet celebrities in their own right. "Loyola 2L," a law student who helped raise public awareness about the risks and costs of going to law school, was named Lawyer of the Year in 2007 by the Wall Street Journal Law Blog.

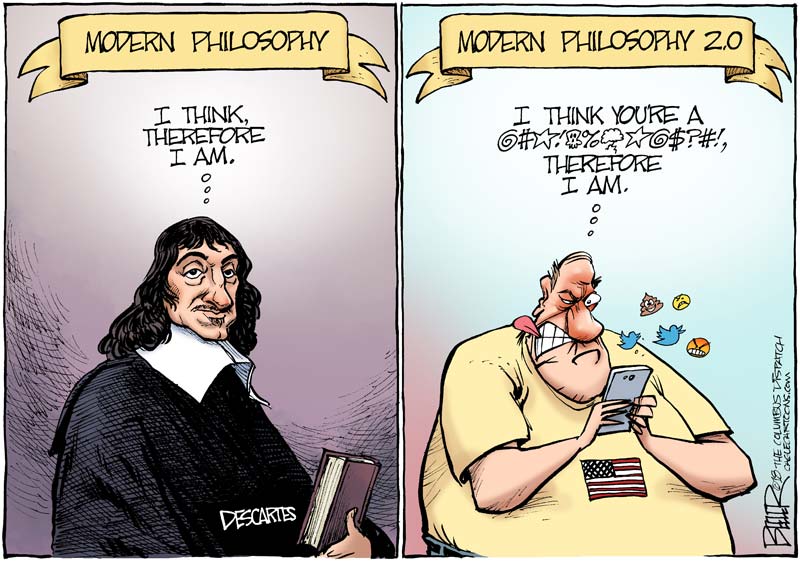

Over the years, however, our comments changed. They had always been edgy, but the ratio of offensive to substantive shifted in favor of the offensive. Inside information about law firms and schools gave way to inside jokes among the "commentariat," relevant knowledge got supplanted by non sequiturs, and basic civility (with a touch of political incorrectness) succumbed to abuse and insult. A female Supreme Court justice was called a "bull-dyke."

An Asian American woman's column about civility in the legal profession provoked "me love you long time" in response. My colleague Staci Zaretsky, who writes extensively about gender inequality in the legal profession, was told: "Staci, you have plenty of assets, like that fat milky white ass."

So we decided to get rid of the comments section.

In part, our decision was based on science. Researchers have found that when readers are exposed to uncivil, negative comments at the end of articles, they trust the content of the pieces less. (Scientists dubbed this the "nasty effect.") A study by the Atlantic found that negative comments accompanying a news article caused readers to hold the article in lower esteem. In an increasingly competitive media environment, websites can ill afford to have their content and brands tarnished in this way.

And then there's the toll comments take on individual journalists. As writer Jessica Valenti explained, "For writers, wading into comments doesn't make a lot of sense - it's like working a second shift where you willingly subject yourself to attacks from people you have never met and hopefully never will."

This is especially true for women and minorities. The Guardian found that of its 10 regular writers who get the most abuse in comments, eight are women and two are black men, while the 10 writers who get the least hate are all male. Because of hateful online comments, some feminist writers have retired, impoverishing public discourse.

Above the Law's full-time writer-editors are a diverse group. I'm a gay Asian man, and I work with, among others, an African American man and two women. We have all regularly received racist, sexist and homophobic attacks. My colleague Staci, who used to interact with commenters more than the rest of us did, soured significantly on them after one commenter discussed "tag-teaming" her with another commenter while hitting her because, well, she looked like she could take a punch.

Negative comments not based on gender or race can be hurtful and demoralizing, too - and can't be dismissed as sexist or racist drivel. As my fellow lawyer turned journalist Jill Filipovicsaid of her experience with nasty comments: "I doubt myself a lot more. You read enough times that you're a terrible person and an idiot, and it's very hard not to start believing that maybe they see something that you don't."

Despite such problems, our decision to scrap the comments section was difficult, reached only after months of discussion, research and argument. It wasn't a matter of traffic, with comment-related page views accounting for less than 3 percent of our total. Nor was it a matter of advertising; our colleagues who sell ads had no say in the matter (although I suspect they're happy with our decision). And it wasn't a legal issue - the Communications Decency Act provides publishers with immunity from liability over comments left on their sites by third parties.

The real issues were more philosophical. As someone who started writing under a pseudonym, I understood how online commentators - especially risk-averse, reputation-conscious lawyers - often need anonymity to take important but controversial stands, disseminate sensitive information, or speak unpopular truths. As journalists who spend our days holding law firms and schools accountable, we viewed the comments as a way for readers to hold us accountable, whether for sloppy logic, factual errors or typos.

But in the end, we realized that our readers were now engaging with our content on social media in generally civil and substantive ways. We concluded that we no longer needed the aggravation of a comments section on ATL itself. In the words of my colleague Elie, one of the last holdouts, "I felt that readers had the right to criticize me if they invested the time to read my stuff - but now people just criticize me on Facebook."

We're not alone. In 2013, Popular Science shut off its comments. In 2014, Recode, Mic, the Week and Reuters closed down their comments sections. Other sites that have removed comments include Bloomberg and the Daily Beast. According to a 2014 study by journalism professor Arthur Santana, of the 137 largest U.S. newspapers, 49 percent did not allow anonymous comments and 9 percent had no comments at all. After the National Journal eliminated comments on most stories, its website traffic and levels of user engagement increased.

Should we have explored other solutions short of removing comments entirely? Like other news sites, we had already deemphasized comments, by hiding them in our layout and allowing them to be deactivated on selected stories. But neither step stopped the harm caused by comments to our readers, writers and site brand.

We did consider greater moderation or policing of comments, whether by us, site users or a combination thereof. As the experiences of the Guardian and Salon suggest, comments sections can work if sites and editors put in the effort to tend their digital gardens, removing weeds and planting seeds for healthy discussion. As technology blogger Tauriq Moosahas argued, comments should be heavily moderated to promote civil, intelligent conversation; otherwise, they should be removed.

At Above the Law, given our small staff, the intensive resources required for fair and effective moderation, and the human toll moderation takes on the moderators, we decided it wasn't worth the trouble. We'd rather devote our time and energy to working on our stories and interacting with readers on social media - which has the added benefit of evangelizing for our site, increasing our Facebook likes and Twitter followers, and driving traffic to ATL through Facebook and Twitter referrals. Social media has even become one of our main sources of tips.

As Kalev Leetaru put it in Forbes, "By moving the conversation to social media, news outlets not only offload the curation and legal liability to a third party, but now every comment becomes an advertisement to direct additional readers back to the article."

Although I know we made the right decision, with increased enjoyment of my job and decreased anxiety as confirmation, part of me is sad. I will miss our comments and commenters, especially the good ones. And I bear no ill will, even toward the mean ones. I feel about them the way I feel about a perfectly nice ex-boyfriend: We had some good times, we grew apart and we should have split up earlier than we did.

But I wish him all the best - even if I don't need to hear from him ever again.

Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

David Lat is the founder and managing editor of Above the Law, a website covering the legal profession, and the author of the novel "Supreme Ambitions."

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author