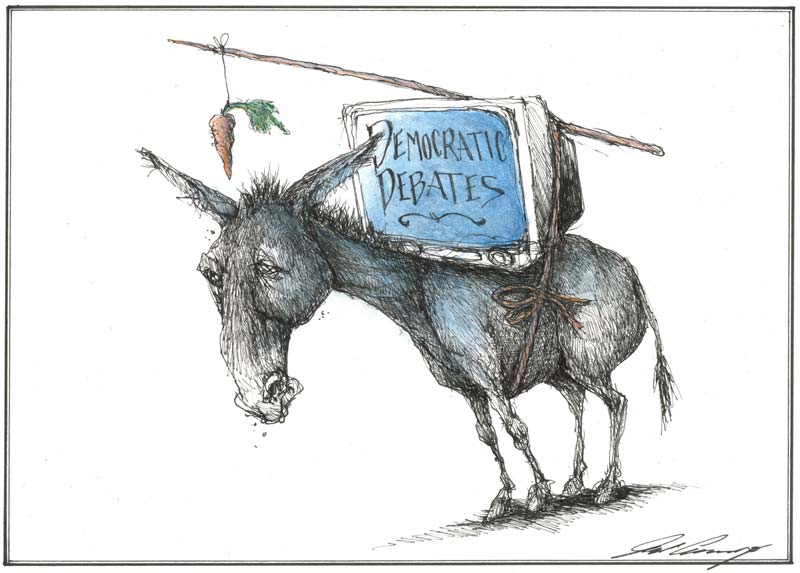

In the first of these Democratic debates last June, the total TV audience (over two nights) topped 33 million. In the second debate, in July, the audience totaled 19.4 million. In the third, it was down to 14 million. It dropped again for the fourth, and for the fifth, and by the time candidates and moderators walked onto the stage at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles for the sixth of these affairs, the audience had dwindled to a mere 6.1 million. How low can it go?

Voters usually grow more, not less, interested as an election campaign unfolds, so by now vast multitudes should be avidly following every word of these debates. Instead, multitudes are doing the opposite, repelled by these tiresome, shallow, and predictable scrimmages. Presidential? That's the last thing they are. These gaudy TV events, with their high-tech gimcracks and game-show atmosphere, aren't forums for grappling seriously with genuine disagreements over policy. They're arenas for silly entertainment. Like WWE wrestling, minus the gravitas, as someone once said.

The deficiencies of our televised debates are an old story. As far back as 1990, the late Walter Cronkite called them an "unconscionable fraud." If you've watched even one of these encounters, you know that they involve no actual debating. The candidates aren't interested in vigorously contending for competing policy differences. Their goals are to deploy their carefully honed talking points, to avoid stumbling into a gaffe, and — if the opportunity presents itself — to zing an opponent with an extemporaneous rebuttal carefully planned in advance.

Nowhere is it written that White House hopefuls must debate. Until Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy met in a CBS studio in Chicago in September 1960, no presidential candidates had ever faced off in that way. But if we are to have debates, they ought to be more than two hours of grandstanding soundbite theater. Their purpose should be not to see who can come up with the most memorable punchline or the sharpest opposition-research barb, but to give voters some insight into the thinking and substance of people who want to be president, and some insight into how they would conduct themselves in the highest office in the land.

How to do that? I offer four improvements:

1. Debate without moderators. If moderators weren't needed for the Constitutional convention debates in Philadelphia in 1787 or for the Lincoln-Douglas Senate debates in 1858, they certainly aren't needed for presidential candidates in 2020. Let two or more candidates sit down at a table with a single microphone and an agreed-upon topic, and have at it for 90 minutes, on air. Viewers could draw their own conclusions: Who drove the discussion? Whose arguments were persuasive? Who had facts and logic at their command? Who merely pontificated?

2. Discuss books. Great literature can shed light on challenging dilemmas and highlight the power of human character and motivation to resolve them. Why not invite candidates to read a classic work, then appear on camera to wrestle with the issues it raises? After studying Shakespeare's "Julius Caesar," for example, they could analyze why Brutus feared Caesar's ambition, and whether his assassination was justified. They could take up "Lord of the Flies," William Golding's 1954 masterpiece, and explore whether human beings instinctively seek peaceful cooperation, or gravitate to violence and domination. They could read Martin Luther King Jr.'s "Letter from Birmingham Jail" and debate how a free society can recognize an unjust law and when civil disobedience is an appropriate strategy for changing such laws.

3. Workshop a crisis. How would a president react in an emergency? Obviously we can't be certain in advance, but candidates could be confronted with an unexpected scenario, and forced to "respond" in real time: An Air Force fighter crashes over the Persian Gulf, and an Islamist terror group is taking credit. The "Big One" has struck along California's San Andreas fault, leaving Pomona and San Bernardino in ruins. Cyber-anarchists simultaneously strike Bank of America, Chase, and Capital One with a paralyzing computer virus, unleashing havoc in financial markets and triggering a 1,000-point stock market selloff. What would the candidates do first? To whom would they reach out? What orders would they give? What choices would they face? What would they tell the nation?

4. Conduct formal debates. Real debate could have real value, if candidates were given sufficient time to make their case and rebut their rivals. Instead of the 45-second soundbites they're allowed now, with moderators skipping from question to question, a formal debate would require each participant to address at length a central proposition — e.g., "A wall should be built along the Mexican border" or "The $21 trillion national debt must be paid down." Candidates would be given a block of eight minutes each to make their case, plus two minutes for rebuttal after the others have spoken. The moderator's only role would be to keep time — no questions, no interruptions. Viewers would decide for themselves whose arguments seemed most thoughtful, prudent, realistic, and presidential. Any of these variations would elevate the tone and deepen the content of the "debates" our candidates engage in now. American democracy deserves better than the spectacle of bickering, quibbling would-be presidents lined up like contestants on "Family Feud." After all, what is the point of debates that fewer and fewer voters want to watch?

Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author