Thirty years ago last month, on Sept. 26, 1993, a group of eight weary, visionary adventurers "returned" to Earth after two years of living together in a miniature version of our world — a hermetically sealed, self-sustaining vivarium of the type we would need to one day settle on Mars, with no air exchange from the outside.

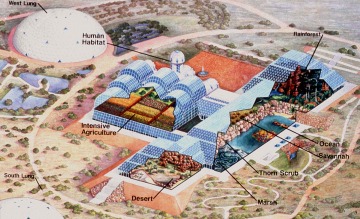

Spanning 3.14 acres in Oracle, Arizona, Biosphere 2, as it was known, was the largest closed system ever created, replete with a rainforest, mangrove wetland, savannah grassland, fog desert, and nearly 4,000 animal and plant species. The earthling inhabitants included four women and four men; all were 20- and 30-somethings — except for one man, a medical doctor, who was 67 — and all had educational backgrounds in either the sciences or engineering.

They had entered Biosphere 2 two years prior with much fanfare and lavish attention splashed their way by the news media. Discover magazine called it "the most exciting scientific project to be undertaken in the U.S. since President Kennedy launched us toward the moon." But after the Biospherians, as they were calling themselves, nearly starved and suffocated to death, and ultimately splintered into two camps of four who wouldn't talk to each other, the press turned harshly critical. Time magazine would place Biosphere 2 on its list of "100 Worst Ideas of the Twentieth Century."

But Time was way wrong, because by any reasonable measure, Biosphere 2 was a sensational idea. In its bold experimentation, Biosphere 2 revealed the complexity of living on the Moon or Mars.

Things started going poorly at Biosphere 2 rather quickly. Early into the mission, the ambient levels of carbon dioxide began to rise, peaking at 20 times that in Earth's atmosphere. Animals started dying. The pollinators — butterflies and bees — were among the first to go. Vegetable production was low as a result of the filtered sunlight. The chickens weren't laying that many eggs. They were soon slaughtered with the dairy goats for their meat because they were eating more than they were providing.

Cockroaches, imported purposely to help break down leaf litter, reproduced splendidly, along with the ants, lots and lots of longhorn crazy ants. No one was exactly sure what happened to the hummingbirds, but the bush babies (small primates) were the leading culprit, snatching them for food. Alas, the bush babies eventually died of starvation. Indeed, almost every vertebrate died — fish, bird, mammal. Starvation was setting in for the crew, too. Of the 30-plus crops planted, only sweet potatoes did well. The crew ate these three times a day, enough to make their hands turn orange with beta-carotene. They also needed to eat their seed crop to survive.

Someone did figure out the O2/CO2 problem. Seems that bacteria in the vast amounts of muck and compost brought into the dome to fertilize the farmland were inhaling O2 and exhaling CO2 just like humans do, only in far greater quantities. Worse, precious oxygen gas was slowly disappearing. It took months before the crew understood that the concrete in one of the biomes was absorbing the oxygen. After a year in Biosphere 2, oxygen had decreased from about 20% to 13% of the atmosphere, resulting in an oxygen level equivalent to what mountaineers breathe at 17,000 feet. The crew was huffing and puffing through the day and suffered from sleep apnea at night. By early 1993, they needed to open the airlocks to allow fresh oxygen to permeate the artificial biosphere, breaking the primary protocol of the mission. Nevertheless, the crew survived, stepping back into Biosphere 1 (that's Earth) two years and 20 minutes to the day after they had left, on average about 30 pounds thinner but otherwise healthy.

The Biosphere 2 project did do several things correctly. For starters, it succeeded in being a fully sealed environment, something that NASA has since learned from. The infrastructure never failed. The facility recycled all of the spent water and sewage, too. NASA has never achieved a total water recycling rate on the International Space Station, but total or near-total water recycling will be essential for all long-term space missions.

Because of Biosphere 2, we now know what not to do on Mars and elsewhere. Don't mix your farm area with your living space; keep it in a separate dome. Don't rely on plants to supply all your oxygen, at least not at first. Don't build big; go small and ramp up. Don't think you can master the web of life by importing one animal to control another. Don't underestimate the power of bacteria. And, for the love of god, don't ever plant morning glories. They will take over your rainforest.

While Biosphere 2 continues to be wrongly disparaged as a failed hippie experiment, rigorous science continues there. The University of Arizona took over research at the facility in 2007 and has initiated studies on atmospheric science, soil geochemistry and, most recently, the Space Analog for the Moon and Mars. SAM, as it is called, is a next-generation hermetically sealed habitat that provides the most realistic earthbound experience of living on Mars.

Within two decades, scientists and engineers will be living on the Moon in simple habitats similar to bases in Antarctica, with food flown in. Mars is too distant to service with regular supplies; if we are to live there for any extended time, we will have to learn how to be self-sufficient to generate and recycle air and water and grow food in a 100-percent closed loop. With any luck, 30 years hence, we may finally be living on Mars with lessons learned from Biosphere 2.

Christopher Wanjek is the author of "Spacefarers," some passages from which appear in this essay (Harvard, 2020). He is also co-author, with NASA photographer Chris Gunn, of "Inside the Star Factory: The Creation of the James Webb Space Telescope, NASA's Largest and Most Powerful Space Observatory" (MIT Press, 2023).

(COMMENT, BELOW)