Just one problem: There is no such thing.

The Patriot Act passed in the wake of the 9/11 attacks includes a definition of national terrorism. But neither it nor the rest of the U.S. Code contains a domestic terrorism statute as such. All the federal prosecutions under U.S. terrorism laws have involved foreign defendants.

That is why, Bash's rhetoric notwithstanding, if Crusius is prosecuted under federal law, it will be for hate crimes and firearms offenses.

By contrast, 18 U.S. Code § 2332b lays out a laundry list of "acts of terrorism transcending national boundaries," - i.e., acts of international terrorism - with commensurately serious penalties, including sentences of death.

The 2,300-word document that Crusius apparently posted online minutes before starting his rampage Saturday warns of a "Hispanic invasion of Texas" and that white people were being replaced by others.

If there were a domestic terrorism statute, would it provide a better fit for Crusius and the suspect in the other mass shooting in Dayton, Ohio, Connor Betts?

In Crusius's case, arguably. Based on his writing, it appears easier to fit his mental state into an intent to "intimidate a civilian population or to influence the policy of government," as opposed to particular animus against Hispanics. And "immigrant status" per se is not a protected class under the hate crimes statute.

As for Betts, whose attack killed nine people before he was shot and killed by police, preliminary evidence has not revealed any particular political or racial motive.

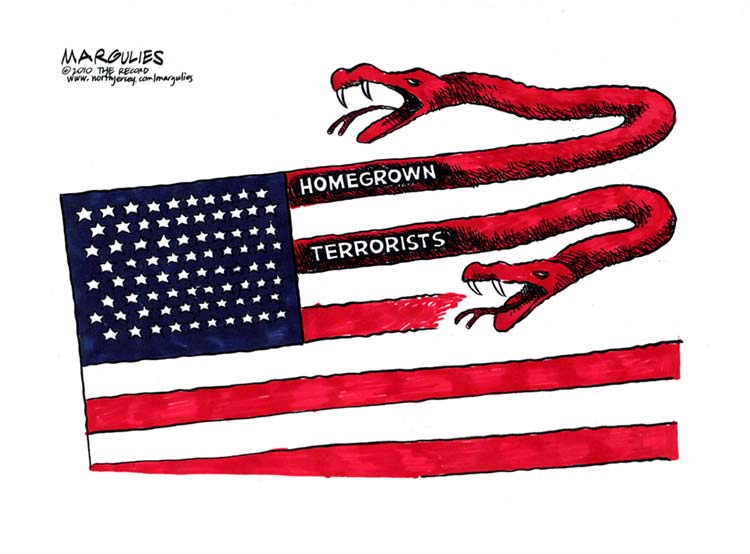

In any event, these two latest tragedies raise anew the need for Congress to pass a discrete domestic terrorism statute.

Opponents of a free-standing domestic terrorism statute point out that between federal hate crime law and state homicide statutes, law enforcement has extensive tools to prosecute domestic terrorists.

Ironically, the same argument was made by opponents of hate crime statutes when they were passed in the 1990s. Why load up the already bloated federal code when assault and homicide statutes were available?

But just as the social evil of hate crimes is particular to those offenses, domestic terrorism is its own evil, and it's fitting for the legislature to recognize the threat and injury that terrorism occasions, and, in fact, to put it on relative equal footing with international terrorism. Fitting, too, that perpetrators of domestic terrorism be branded with the scarlet letter signifying particularly abhorrent crimes.

That is especially the case given that, according to the latest FBI reports, the threat of white nationalist violence appears to be intensifying

And while it is doubtful whether the actors in such rampages are subject to normal forces of deterrence, it also is fair, and consistent with due process, for the law to call out the specific criminal conduct that the law forbids and the specific penalties the violations entail.

It also would, to some degree, increase social awareness of the domestic terrorism offenses. As Juliette Kayyem argued in a column for The Washington Post, true "lone wolf" assailants are rarer than people think; many mass shooters emerge from an online social setting that nurtures their demented views.

But passage of a domestic terrorism law would have important substantive effects as well. It would also bring such crimes into the rubric of predicate offenses for providing material support to terrorists. And, as the FBI has pointed out, it would also provide more resources for the bureau on the data-gathering side as well as the prosecution side.

The time is more than ripe for passage of a criminal domestic terrorism statute. This would be a small, constructive development to emerge from the recent rash of tragedies.

Every weekday JewishWorldReview.com publishes what many in the media and Washington consider "must-reading". Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Harry Litman is a former U.S. attorney and deputy assistant attorney general. He teaches constitutional law and national security law at the University of California at Los Angeles School of Law and the University of California at San Diego Department of Political Science. Litman served as a law clerk to Supreme Court Justices Thurgood Marshall and Anthony Kennedy. Prior to law school, Litman worked on the Associated Press baseball desk and as a feature film production assistant in New York City.

Previously:

• 02/14/19 The Roberts court may have 'Roe v. Wade' in its sights. But it is taking things one step at a time

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author