The junior senator from Massachusetts was Paul Tsongas, a liberal Democrat from Lowell. I was neither a liberal nor a Democrat — like most younger voters then, I supported Ronald Reagan (yes, most: You can look it up ) — and I didn't share many of Tsongas's political stands. But I liked his style.

Tsongas was thoughtful and self-deprecating and not arrogant; he seemed willing to consider the opinions of others and to acknowledge when his judgment had been wrong. In a city and a profession filled with arrogant partisans, he wasn't blind to his own party's shortcomings. Indeed, he sought to correct them.

In perhaps his most famous speech, Tsongas addressed the national convention of Americans for Democratic Action on June 14, 1980. The ADA has faded from view now, but in those days it was an influential organization that stood for unabashed New Deal liberalism and worked steadily to push the Democratic Party to the left.

Tsongas was just a freshman senator with little seniority on Capitol Hill, while the other senator from Massachusetts was the far more influential Ted Kennedy, whose insurgent campaign for president that year had just moments earlier been wildly cheered by the ADA delegates.

So it took a measure of guts for Tsongas to deliver the blunt message he had come that day to share: that Kennedy-style liberalism wasn't working.

"Fewer young people are joining the liberal cause in 1980 than in the 1960s," he warned. "Liberalism is at a crossroads. It will either evolve to meet the issues of the 1980s or it will be reduced to an interesting topic for PhD-writing historians."

The delegates' reaction, he later noted dryly, was not exactly an ovation. But his purpose that day wasn't to be lauded. It was to be heard.

"Liberalism must extricate itself from the 1960s," Tsongas said. "We must move on to the pressing problems of the 1980s, and we must have answers that seem relevant." Americans are frustrated, he said, and "many are looking to Ronald Reagan for leadership."

Reaction to the speech was intense. Hard-core liberals accused Tsongas of selling out, or of betraying his senior Senate colleague. But from younger liberals and moderate Democrats came a deluge of praise, and thousands of requests for copies of his speech. Then-US Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York pronounced it the best address delivered to an ADA gathering since his own in 1967. A year later, the speech was expanded into a widely praised book, The Road From Here.

The junior senator from Massachusetts turned out to be right. The Democrats lost the White House that November and 12 years would elapse before they regained it. Tsongas himself, facing a battle with cancer, retired from the Senate after the 1984 election. He died of lymphoma in 1997 at the age of 55.

Why can't Massachusetts elect more Democrats like Tsongas? I don't mean Democrats who describe themselves as neoliberals, though that wouldn't be so bad. I mean Democrats who are willing to challenge their party's knee-jerk verities, who aren't locked into an ideological straitjacket, who are more interested in governing well than in scoring meretricious debaters' points.

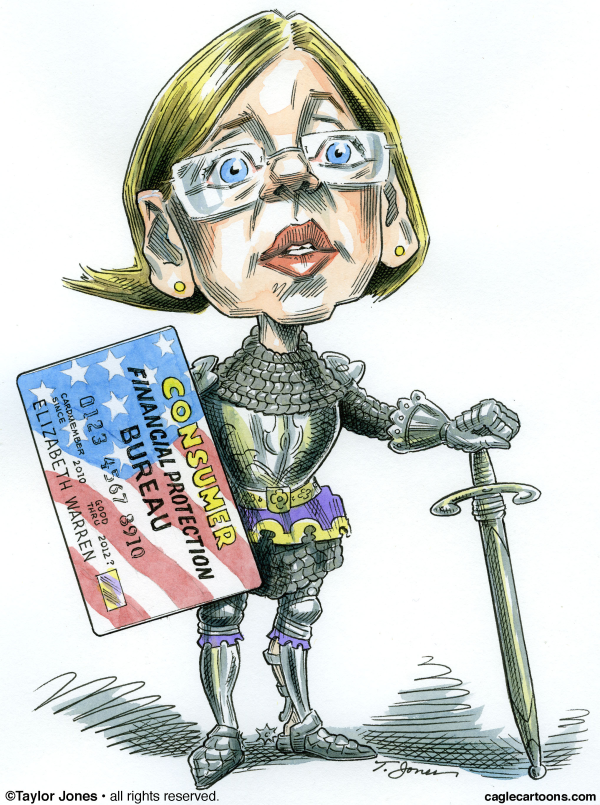

Democrats, in other words, who aren't like Elizabeth Warren.

In general I have a low opinion of politicians, most of whom strike me as cunning but not contemplative — far more focused on chasing popularity than on shaping careful public policy. The other senator from Massachusetts, Ed Markey, seems to me to be that sort. I generally don't like or agree with the things he says and does, but I also don't expect more from him.

But it's different with Warren. Before she entered Congress, she was nothing like the snide left-wing propagandist she is today. Certainly she was a liberal, but she didn't treat all private enterprise and successful businesses as slimy lowlifes, guilty until proven innocent. Back then, she wasn't seeking a reputation for herself as an avenging hard-left crusader, quick to eviscerate any Republican or conservative with a difference of opinion.

Read The Two-Income Trap , the interesting and judicious book about economic insecurity that Warren co-wrote with her daughter in 2004, and you encounter someone who was thinking about important social issues in ways that didn't line up neatly with the usual left- and right-wing shibboleths. For example, she endorsed school choice, arguing that parents should be given vouchers to enable them to send their children to schools anywhere in a district. She pointed out that the migration of women into the workforce that began in the 1970s had come with significant downsides for their families ("They saw the rewards a working mother could bring, without seeing the risks associated with that newfound income. . . . The combination has taken these women out of the home away from their children and simultaneously made family life less, not more, financially secure.")

I realize that political ambition doesn't bring out the best in most people. But once Warren jumped into electoral politics, she seemed to go out of her way to signal that her days of nuance and moderation were over. She advertised herself as a Democrat who could guarantee that there'd be "plenty of blood and teeth left on the floor " in any legislative battle she took on. Before long the law professor and financial expert who thought outside the usual boxes and appealed to more than just her party's true believers was gone. In its place was an ultra-combative ideologue, quick to take offense and fling insults.

To be fair, Warren is hardly the only member of the Senate who is disappointing in this way. The Republican caucus, too, includes members who used to be seen as affable and intellectually impressive, but have transformed themselves into zealous bomb-throwers: Ted Cruz of Texas and Josh Hawley of Missouri , for example. But Warren is my senator, which is why I focus on — and am so disappointed in — her. American politics desperately needs leaders who want to cool partisan fevers, who value compromise, who live by the principle that disagreement need not always be disagreeable.

Warren could have been such a leader, but chose to go in a different direction.

IN THE WORLD ACCORDING TO WARREN, INFLATION IS GREED

For a good illustration of Warren's style, consider the explanation she gave for why turkey was more expensive this season: "plain old corporate greed," she called it. Americans had to pay more for turkey, Warren charged, because poultry companies abused their market power, "giving CEOs raises & earning huge profits."

As it happens, corporate greed is also Warren's explanation for the fact that the price of gasoline is so much higher.

"Giant oil companies like Chevron and ExxonMobil enjoy doubling their profits," she tweeted last month. "This isn't about inflation. This is about price gouging."

Can you guess why the cost of renting a car has gone up so much? According to Warren, the main explanation is — yep — corporate greed.

In a letter Dec. 7 letter to the CEO of Hertz, Warren blasted the company for being "happy to reward executives, company insiders, and big shareholders" with stock buybacks, "while stiffing consumers with record-high rental car costs."

Elizabeth Warren's economic explanations bear a certain resemblance to Henry Ford's Model T.

The price of meat is up? Warren slams "meatpacking monopolies that are using inflation as cover to raise prices and make record profits." A shortage of computer chips has caused a spike in the price of new cars? "Market concentration has reduced competition, allowing giant corporations to deliver massive returns for shareholders," declares the Massachusetts senator. Grocery bills are steeper? Warren attacks "large grocery retailers [that] are earning massive profits for company officials and investors while making it harder for American families to put food on the table."

Like Henry Ford, who would sell customers a Model T car in any color they wanted as long as the color was black, Warren will gladly explain why prices are rising for any product — as long as the explanation involves greedy businesses out to make more profits.

It is absolutely true that corporations are always looking for ways to increase their profits. That's how they survive. The reason businesses exist in the first place is to supply goods or services to customers and make money doing so. If companies can't make a profit, they eventually go out of business and no longer sell those goods or services.

But if corporate greed is Warren's one-size-fits-all explanation for why prices go up, how does she explain why prices go down? Corporate benevolence?

Take gasoline. In the spring of 2020, the average price of gasoline plunged to less than $1.90 a gallon . Why weren't Chevron and ExxonMobil doing then what Warren claims they are doing now — "gouging" customers to boost profits? The answer, of course, is that prices are driven by supply and demand, not by all-powerful capitalists capable of "doubling their profits" whenever they feel like it. Last spring, the pandemic and its attendant worldwide lockdowns caused a drastic cut in demand, which led in turn to a sharp fall in prices — so sharp, in fact, that the oil industry suffered an unprecedented crash.

In 2020, the five largest oil companies (ExxonMobil, BP, Shell, Chevron, and Total) lost a combined $76 billion. When the economy recovered and the demand for oil grew faster than the inventories available to meet it, prices soared.

In the world according to Warren, every unwelcome spike in prices is the result of cupidity by multimillionaires exploiting their power to put the screws to consumers, while every dramatic price reduction is an irrelevancy. In the real world, market forces, not corporate villainy, explain why prices fluctuate. And "market forces" go far beyond decisions made by a handful of executives in C-suites. They comprise the choices made by tens of thousands of producers and vendors, as well as millions of transactions by consumers.

"The focus on corporate greed is an absurdly reductive depiction of the US economy," observes Rich Lowry in an essay appearing in JWR. The supposed monopolistic power of corporate America to set prices at whim makes no sense. Did the American economy, after 30 years of notably low inflation, suddenly become more concentrated earlier this year, such that companies could arbitrarily jack up prices? And why was it that this economic power made itself felt just as supply chain disruptions took hold and the Democrats' massive COVID relief bill further stoked demand in an already growing economy?

If greedy corporations are to blame, they are at work across the board. In November, food prices were up 6.1 percent from the year before, with meat, poultry, fish, and eggs up 12.8 percent, cereals and bakery products up 4.6 percent, and nonalcoholic beverages up 5.3 percent. Energy increased 33 percent. All other commodities outside food and energy jumped 9.4 percent. Used trucks and vehicles went up 31.4 percent.

Is inflation on the march because, after so many years of stable prices, corporate America was suddenly seized by a wave of greed? I have too much respect for Warren's intelligence to imagine she really believes that. I think it more likely that she imagines a lot of other people believe it (or want to believe it), and is shamelessly angling for their support.

I know that cynicism and demagoguery are as old as politics. I suppose it isn't fair to expect Warren to hold herself to a higher standard of intellectual integrity than any of the Senate's other cynics and demagogues. But as Warren plays the corporate-greed card over and over again, like a dreary relative repeating the same party trick at every family gathering, I think of Paul Tsongas.

I remember what it was like to have a senator who treated his constituents, and the nation's discourse, with genuine respect. I wish I still did.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author