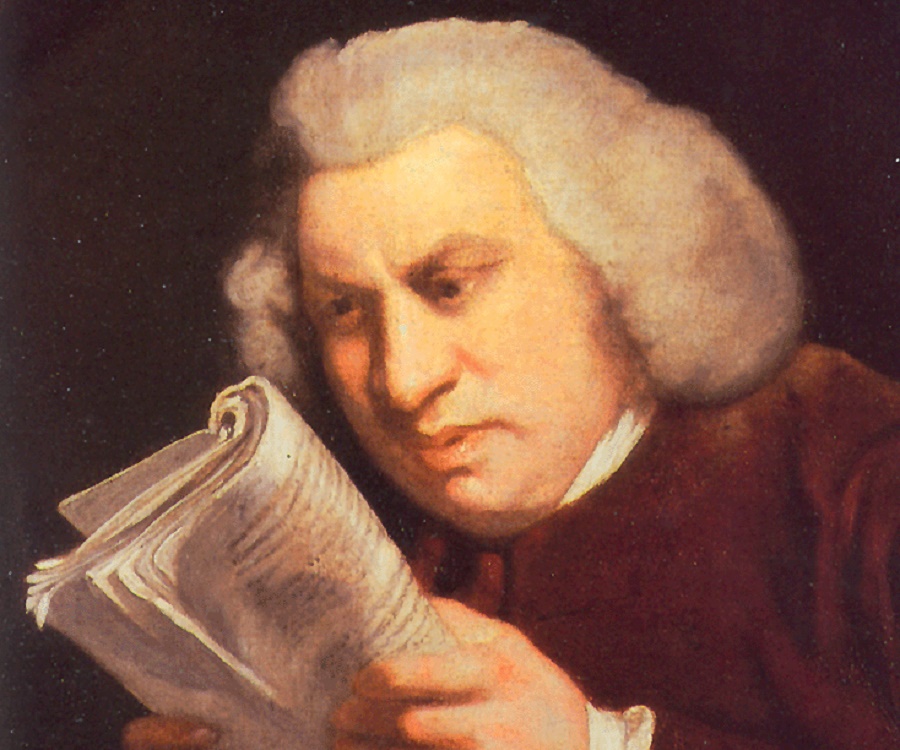

Dr. Samuel Johnson.

Dr. Samuel Johnson.

How small, of all that human hearts endure,

That part which laws or kings can cause or cure!

Still to ourselves in every place consigned,

Our own felicity we make or find.

I agree even more strongly with King David, who wrote in the 146th Psalm: "Put not your trust in princes."

Politics, especially American politics in the system devised by the Founding Fathers, wasn't supposed to matter to us as much as it does. It wasn't supposed to be so all-consuming, so ubiquitous, so fatiguing. Indeed, one of the reasons America adopted an indirect, federal system of politics was to liberate most citizens most of the time from the grind of having to constantly think about politics and forever be making political decisions. The people were to be free, and the point of freedom wasn't to be political.

Writing to his wife Abigail from Paris in 1780 — he was negotiating with the French government on behalf of the fledgling American government, then still at war with Britain — John Adams expressed the view that while he had no choice but to toil daily in political affairs, he wanted better for their children and grandchildren:

I must study politics and war that my sons may have liberty to study painting and poetry, mathematics and philosophy. My sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history, naval architecture, navigation, commerce, and agriculture, in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry, and porcelain.

Politics, in this view, is like plumbing or agriculture or banking. It is important work, and no healthy society can survive without it, but it doesn't need to be on everyone's mind every day of the week. Ideally, it would attract good and conscientious people, who could, for the most part, be trusted to take care of the nation's political affairs, just as we trust other people to play the dominant role in other areas of life — business, journalism, the arts, medicine, sports.

Politics, as Bonnie Kristian writes, is meant to be "a servant to better pursuits."

It is not our highest obligation, the sum of "the things we choose to do together" [in Barney Frank's famous phrase]. It is a necessary but not especially noble substrate on which we build greater things.

Yes, politics matters. Of course politics matters. I spend much of my days writing about why and how it matters. But it does not matter most. It is not our most important commitment or identifier. It is not our greatest concern or responsibility. Or rather, it should not be.

Yet what is and what should be are rarely the same, and I am not optimistic that the political will cede the mental territory it has captured.

Me neither. Politics has always loomed too large, and I would argue that that is at least in part because government looms so large.

Large majorities of Americans consistently say they don't trust the federal government and have little faith in the ability of Washington's immense bureaucracy to solve the nation's problems. That alienation from government did not begin under Trump or Obama or Bush; it has been growing for at least half a century, roughly in proportion to the self-aggrandizement of the federal establishment.

As Charles Murray has written, the more Washington has tried to do, the less it has done well, including the relatively few functions it used to perform competently. There is widespread frustration with the intrusive, expensive federal behemoth and a nonstop drumbeat of calls for it to be doing even more.

Over the past several generations, the government has insinuated itself into a 1,001 decisions that individuals or local governments are more than capable of making for themselves. Which medicines can you buy? How efficient should your light bulbs be? What should be included in your children's school lunch? Who qualifies for a mortgage? When do unemployment benefits run out? Can you pay a worker $6 an hour if that's all his labor is worth? Should abortions be restricted? Is health insurance optional? Do artists or farmers or broadcasters require subsidies? Are you in charge of your retirement income?

The flow of power upward to the federal government has impoverished American culture and weakened civic society — and it has made more and more of us obsessed with politics, since more and more seems to ride on the outcome of each election.

But does it really?

In an essay that appeared in JWR, John Stossel offers the refreshing and reassuring reminder that despite all the bandwidth consumed by the candidates, the elections, the news coverage, and the campaign ads, the most important parts of life still happen outside politics.

"Love, friendship, family, raising children, building businesses, worship, charity work — that is the stuff of life! Politicians get in the way of those things," Stossel writes. "But despite the efforts of power-hungry Republicans and Democrats, life gets better."

I've lived through the Vietnam War, a military draft, 90 percent income tax rates, price controls, indecency laws, widespread racism and sexism, Jim Crow, the explosion of crime in the 1970s. . . .

Overall, life got better.

With Donald Trump and Joe Biden claiming the other will destroy what's good, it's hard to see improvement. But the world has made progress, largely thanks to libertarian ideas.

No one denies that America has problems — the coronavirus, crime, unemployment, wildfires, homelessness, right- and left-wing extremism, suicides. Every age has its problems; every problem exacerbates social fears and political recriminations. Human beings are hardwired to focus on what's wrong, and our bias toward negativity is fodder for politicians on the make.

And yet the world keeps improving. In a column last December — "What was so great about the 2010s " — I wrote that "far from living in a uniquely awful era, we are living in the best era our species has ever known." On the cusp of 2020, the good news could be seen everywhere: Human lives are longer, more babies survive to adulthood, extreme poverty has been in retreat, literacy is now almost universal, girls are more educated than ever, food supplies are at all-time highs, climate-related deaths are at all-time lows, and on and on. At the time, no one knew that a pandemic was on the way, but just as Ebola and polio and AIDS were beaten back, COVID-19 will be defeated too.

"I obsess about problems," admits Stossel. "But I try not to let that distract me from the big picture.

More people in more places enjoy prosperity, religious freedom, personal freedom, democratic governance, largely equal rights, civility, better health, and longer lives.

Neither Trump nor Biden is likely to destroy that.

I write about politics and political affairs for a living, but I learned long ago not to put my trust in princes. Good politicians can sometimes make things better, and God knows bad politicians can make things worse, but politics doesn't make the world go round.

Like countless Americans, I wait to learn the outcome of yesterday's vote with trepidation. I know that no matter who wins the presidency, no matter which party controls Congress, government is going to be a source of aggravation and angst.

But I also know that life is mostly lived outside the realm of politics.

Elections matter, but other things matter more.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author