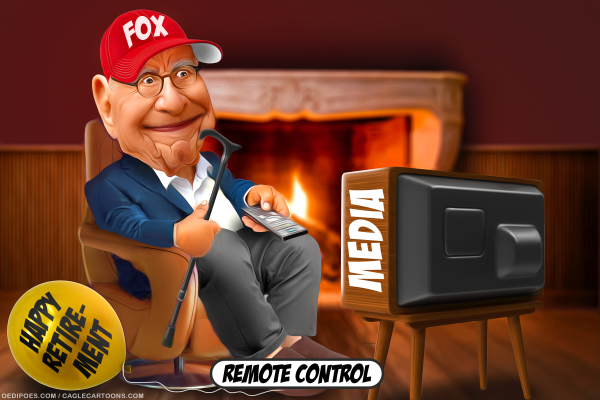

Rupert Murdoch's announcement that he will step down in November as the chairman of Fox Corp. and News Corp., the linchpins of his media empire, attracted instant and massive attention. It could hardly have done otherwise. Murdoch is the most important and transformative media baron of the last two generations — global in reach, mighty in influence, brilliant in insight, relentless in drive, and very, very polarizing in impact.

Much of what is admirable about the contemporary media landscape can be traced to Murdoch. Perhaps the best example is the excellence of The Wall Street Journal. Murdoch acquired the paper in 2007 and greatly improved it, expanding its international journalism, adding a weekend edition, and building it into one of the nation's most trusted media brands.

More generally, Murdoch has been a sustainer of newspapers over his long career, "keeping them," as Roger Cohen of The New York Times once wrote, "alive and vigorous and noisy and relevant."

Unhappily, much of what is awful about the contemporary media landscape can also be traced to Murdoch. Of that there is now no better illustration than the Fox News Channel, which he launched in 1996. Fox News began as a refreshing alternative to the stifling liberalism of mainstream TV; its hosts were conscientious journalists like Tony Snow and Chris Wallace; it featured cerebral conservative analysts like Charles Krauthammer and George F. Will. But in recent years, Fox turned into a cynical outlet for the worst sort of right-wing trollery, embracing and promoting the ugly xenophobic populism of Donald Trump and his cultists. Not only did it adopt sins it had long decried in the left-wing media ecosystem — partisan loyalty, blinkered news judgment, the peddling of ideological propaganda — but it did so aggressively and recklessly, especially after the 2020 election. Tellingly, the original motto of Murdoch's flagship network, "Fair and Balanced," was dropped in 2017.

Still, there is more to the Murdoch legacy than cable news, as Boston has particular reason to know.

In the early 1980s, long before Fox News existed, Boston was well on its way to becoming a one-newspaper town. The old Boston Herald American was dying. Its owner, the Hearst Corp., was letting it expire. Local investors had no interest in spending the money it would require to save the city's No. 2 paper.

But the newspaper magnate from Australia did. As he had done with The Sun in London and The New York Post, Murdoch revived a paper that had been headed for bankruptcy. Before long the Herald was once more a vital part of Boston life, breaking stories and providing a distinct editorial voice to compete with the Globe's in the marketplace of ideas. By the time I joined the Herald as its chief editorial writer in 1987, the paper's daily circulation had climbed to 360,000 — something that would have been unimaginable a decade earlier.

And then, of a sudden, the knife was back at the Herald's throat. In what became one of the biggest media stories of 1988, Senator Edward Kennedy — a frequent target of the Herald's journalistic scrutiny and editorial criticism — arranged for an anti-Murdoch provision to be furtively slipped into a massive federal spending bill. At the time, a federal restriction known as the cross-ownership rule prevented any individual from owning both a newspaper and a broadcast station in the same city, unless the Federal Communications Commission granted a waiver. Murdoch, who owned the Herald and the local Channel 25 TV station, had such a waiver, but Kennedy's rider directed the FCC to revoke it, thereby forcing Murdoch to jettison one of his two local properties. (It imposed the same bitter choice in New York, where Murdoch owned a feisty tabloid, the Post, as well as a TV station.)

Since Murdoch's long-term strategy was to create a TV network, most observers assumed — or, in the case of those of us working at the Herald, feared — he would sell the paper. No one was under any illusions about Kennedy's hostile motive. Even the Globe suggested that Kennedy was "settling some nasty political scores in the family tradition" and paving the way for the Herald to be acquired by "owners less hostile to his politics."

I was assigned to write an editorial laying out the Herald's case. It ran across the top of Page 1 beneath the headline "Kennedy's vendetta." The editorial acknowledged that the paper had frequently been critical of the senator and his politics. But whereas the Herald assailed Kennedy openly, it observed, he went after the Herald in a "dead-of-the-night maneuver . . . without debate, without discussion, without deliberation." It felt good to write that editorial. It felt even better when news outlets from Time magazine to USA Today not only quoted it but even reproduced an image of the Herald's front page.

What felt best of all, though, was when Murdoch announced the next day that if he was forced to divest one of his Boston media properties, it wouldn't be the newspaper. "I'm not going to sell the Boston Herald," he declared on CNN. "We're keeping the Boston Herald in spite of Senator Kennedy." He did just that. For the next six years, the Herald remained in Murdoch's portfolio. When he finally did sell it in February 1994, it was to his protĂ©gĂ© Pat Purcell, the Herald's longtime publisher. By that point, the Globe — to which I moved the same month — had been bought by The New York Times Co., which would own it for two decades.

Only once did I have a conversation with Murdoch. In 2008 I attended a dinner he hosted to honor recipients of a journalism prize sponsored by News Corp. A few months earlier, Murdoch had become the owner of Dow Jones, the company that publishes The Wall Street Journal. I told him I wished he had chosen instead to acquire the New York Times Co., which was imposing one misery after another on the Globe and its employees.

"Oh, I don't want to own the Times," he replied with a grin. "I want to drive it out of business."

So he said, but if there was one thing Murdoch never wanted to do, it was put newspapers out of business. His sins may be many, but a love of newspapers has always been among his greatest virtues. He helped make possible the last golden age of print newspapers, and he ensured that at least some of them would survive into the digital age. In America today, only a handful of major metropolitan areas still have two daily newspapers. Thanks to Murdoch, Boston is one of them.

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe, from which this is reprinted with permission."

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author