The Hevolution Foundation, a lavishly funded organization created to promote research in the field of human longevity, just opened a headquarters in Boston. The Saudi Arabia-based nonprofit, established in 2021, summarizes its mission as "supporting innovation in life sciences and medicine that focuses on the biology of aging" in order to extend "healthy lifespan for the benefit of all humanity." Hevolution — a portmanteau of health and evolution — will make grants to biotech firms, medical schools, and teaching hospitals working to slow aging and combat age-related disease.

The yearning for a longer human life is ancient. Advances in medicine, along with improved nutrition and safety, have dramatically increased life expectancy over the past two centuries. Worldwide, average life expectancy has more than doubled, from the mid-30s in 1900 to more than 70 today. In many rich countries, life expectancy is now above 80. According to the Population Reference Bureau, babies born today in some high-income nations can be expected to live past 100.

But anti-aging researchers like the ones Hevolution intends to support have their sights on even loftier goals. Experiments with mice indicate that the aging process can be dramatically slowed, or even reversed. The Methuselah Foundation, another funder of longevity research, aims at "making 90 the new 50 by 2030." Scientific American reported in 2021 that a human lifespan of between 120 and 150 years could be possible within a few decades. According to Harvard geneticist David Sinclair, it is likely that the first person to live to 150 has already been born.

Most people, I imagine, instinctively applaud efforts to extend human "healthspan." But not everyone.

At a time when any number of voices loudly claim that having children is morally problematic because of climate change or overpopulation or resource depletion, it's hardly surprising that there are also objections to enabling more people to live longer. For years, critics have condemned anti-aging research. Peter Singer, a prominent professor of bioethics at Princeton University who argues that it should be legal to kill severely disabled infants, has declared that policy makers should oppose any development of life-extending drugs on the grounds that "there will soon be more people than the world can support." Far from celebrating all that could be achieved if men and women had longer lives, Singer concludes that "overcoming aging will increase the stock of injustice in the world."

Some years ago, cell biologist Judith Campisi told The New York Times that after giving a lecture at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory on longevity she was accosted by a group of protesters. "How dare you do this research?" they demanded. "The earth is already being raped by too many people, there is so much garbage, so much pollution."

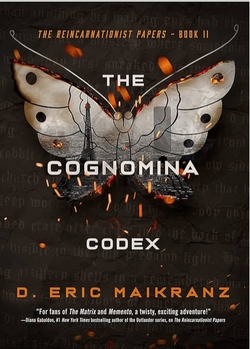

I had been thinking about this topic even before the Hevolution announcement, having recently read The Cognomina Codex, a riveting new sci-fi novel by D. Eric Maikranz. The plot is driven by the passion of one such individual, named Brevicepts, to save the planet from despoliation, species extinction, pollution, and climate crisis — all of them caused, in her view, by too many people. When researchers announce a breakthrough in cell therapy that will dramatically extend human lifespan, Brevicepts calls the news a "setback" and unleashes a covert effort to sabotage the research.

Across her many lifetimes, Brevicepts has steadily worked to "cull" human beings, in the belief that only by reducing lives in the present can the future be improved. Thus, for example, she helped spread bubonic plague in medieval Venice, drastically reducing the city's population through death — a feat she boasts of centuries later. "Venice is an example of the positive results of our work," she contends. Her claim is that by hastening the deaths of many thousands of 16th-century Venetians, she helped make possible the transformation of Venice from a crowded slum to a beautiful modern jewel. By the same logic, she and her followers are convinced that anti-aging therapies must be blocked to ensure the earth's future livability.

This is fiction, of course — and to be clear, Brevicepts is a villain in "The Cognomina Codex." But at least since the time of Thomas Malthus, influential thinkers have insisted that more people must lead to more hunger, misery, and environmental degradation. It's a pernicious fallacy but undeniably seductive.

Fortunately, science and medicine continue, undeterred by the Malthusians and their dread of a world with too many people. The day is coming when living to well past 100 will be the norm and when the diseases of old age will begin decades later than they do now.

The naysayers may fume, but I regret only that my generation won't be here to see it.

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe, from which this is reprinted with permission."

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author