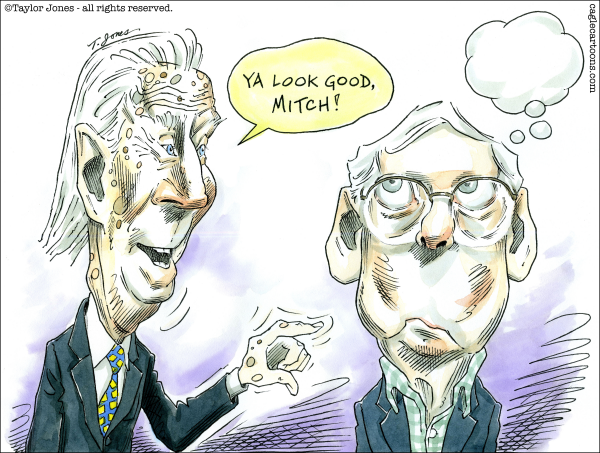

For the second time in five weeks, Senator Mitch McConnell suddenly froze up during a press conference, staring silently for half a minute or so before trying, unsuccessfully, to field more questions. Eventually his aides led him away from the cameras, as they had when something similar occurred on July 26.

Ironically, McConnell had just been asked whether he planned to run for reelection. He chuckled, seemed poised to answer, then abruptly stopped. He never did reply; his spokesperson said only that McConnell momentarily felt lightheaded while speaking with reporters and would consult with a doctor before his next event. On Thursday, his office released a letter from Congress's attending physician pronouncing him "medically clear" for work.

McConnell is old. He was born in 1942 and has been in the Senate for 38 years; in 2020 he was elected to his seventh six-year term. He is the longest-serving Senate Republican leader in the history of the GOP and the longest-serving senator ever elected from Kentucky. He has been in the Senate longer than all but one of its current members. Iowa's Charles Grassley, who has been a senator since 1981, heads the list. California's Dianne Feinstein, who took her seat in 1992, is in third place.

There are other prominent elderly members of the federal government. President Biden was also born in 1942 and his visible signs of age have grown so worrying that more than three-quarters of the public, according to the latest Associated Press poll, think he is too old to run for another term as president. Former House speaker Nancy Pelosi is 83. At least six House members are older than she is.

Washington is more of a gerontocracy than ever — no president has ever been older and the median age of the current Senate is 65.3 years, a record high. Though some House freshmen are in their 40s or younger, the median age in that chamber, too, is the highest it's ever been. McConnell's brain-freeze episodes, Biden's moments of obvious confusion, and the tragic evidence of Feinstein's cognitive decline keep raising questions about the age and health of America's political leaders. Actually, they keep raising just one question: What do we do about geriatric officeholders who refuse to relax their grip on power?

It is not a new conundrum. In "Master of the Senate," his spellbinding account of Lyndon Johnson's transformation into the youngest and greatest Senate majority leader in history, historian Robert Caro recounts how Capitol Hill's unwritten seniority system — the most powerful positions went to the longest-serving members — had become a "senility system."

For example, Caro describes Arthur Capper of Kansas, who became the ranking Republican member of the Agriculture Committee at the age of 75. By that point Capper was already deaf and so frail that one news account described him as "a living shadow, one hand cupped behind his ear and a strained expression on his face" as he struggled to follow a committee hearing.

"[I]n 1946 the Republicans became the majority party in the Senate," Caro continues, "and seniority elevated Capper, now 81, to Agriculture's chairmanship, although by that time, as another reporter noted, ‘he could neither make himself understood, nor understand others.'"

Another example: Carter Glass, a Democrat from Virginia, took over the chairmanship of the Appropriations Committee in 1932, when he was 74. By 1942, he was so ill that he remained at all times in the Mayflower Hotel, never venturing to Capitol Hill. When some of his fellow Democrats proposed in 1945 that Glass, then 87, should step down, his wife replied on his behalf that the suggestion would not be considered.

Has anything changed? When Senator Ted Kennedy was diagnosed with brain cancer in 2008, it quickly became apparent that he would never again be well enough to do his job. After he had been absent from the Senate for 15 months, I wrote a polite column urging him to resign so that Massachusetts could again have two functioning senators. "Few things are harder for those accustomed to power than letting it go," I commented. "But there is no honor in clinging to office till the bitter end."

Needless to say, Kennedy did cling to office till the bitter end. Like 1 of every 6 senators ever sent to Washington, he hung on to his seat until death. So have other senators since then: Robert Byrd of West Virginia (died while in office in 2010), Daniel Inouye of Hawaii (2012), Frank Lautenberg of New Jersey (2013), and John McCain of Arizona (2018).

Pelosi stepped down from the speakership this year, and it is conceivable that McConnell might decide — or be compelled by his caucus — to do the same thing. But the likelihood that he will agree to voluntarily hang up his gloves and retire from the congressional ring altogether seems close to nil. If Carter Glass, Ted Kennedy, and Dianne Feinstein wouldn't go voluntarily, why should any other superannuated member of Congress?

The Constitution establishes no maximum age for senators, representatives, or presidents — only a minimum. Voters could refuse to elect or reelect a candidate who has lost the cognitive or physical stamina to serve in office, but they almost never do. As with most problems in our democratic Republic, the ultimate solution is in the hands of the people. All we have to do is tell our politicians: No more.

I don't know why that should be so hard. As a matter of policy, I routinely vote against incumbents, regardless of party. If my fellow Americans would join me in doing the same for a few electoral cycles, we'd have that gerontocratic deadwood cleaned out in no time. There is no guarantee that Washington would work better if there were fewer septuagenarians and octogenarians pressing the levers of power. But wouldn't it be refreshing to find out?

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe, from which this is reprinted with permission."

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author