During a visit to Australia in 1958 as the Cold War was heating up, Britain's Prime Minister Harold Macmillan expressed the hope that diplomacy and negotiation could defuse the worsening hostility between the Soviet bloc and the West.

"I still believe with Sir Winston Churchill that jaw-jaw is better than war-war," he told an audience in Canberra.

Macmillan was paraphrasing his predecessor, who had actually said, during a 1954 visit to the White House, that "meeting jaw to jaw is better than war." But Macmillan's paraphrase was catchy, and his words have been erroneously attributed to Churchill ever since.

We now know, of course, that jaw-jaw didn't end the Cold War. Decades of diplomatic engagement, détente, and invocations of "peaceful coexistence" never came close to resolving the deep-rooted competition between Washington and Moscow. The two rivals never directly faced each other in battle, but indirectly they fought multiple bloody proxy wars — in Korea, Vietnam, Angola, Afghanistan, and Nicaragua, among others — in which tens of thousands of lives were lost.

What finally finished the Cold War was the internal collapse of the Soviet Union, which led the Kremlin to abandon its longtime goal of world domination. To put it bluntly, the conflict ended because one side clearly won and the other side clearly lost. That is how major international conflicts virtually always conclude — through victory, not negotiation.

"Of the more than two dozen great-power rivalries over the past 200 years, none ended with the sides talking their way out of trouble," writes Michael Beckley, a professor of political science at Tufts University, in the new issue of Foreign Affairs. "Instead, rivalries have persisted until one side could no longer carry on the fight or until both sides united against a common enemy."

It is an enduring misconception that countries get caught up in fierce rivalries because of misunderstandings, failures of empathy, or hawkish domestic politics. Not so, says Beckley. Rival nations feud not because they don't understand each other "but because they know each other all too well. They have genuine conflicts of vital and indivisible interests." Those conflicts often involve territorial disputes or overlapping spheres of influence. But equally common are clashes between rivals who "espouse divergent ideologies" and who regard the success of the other side's values and beliefs "as a subversive threat to their own way of life."

In that Canberra speech 65 years ago, Macmillan, despite hoping that "jaw-jaw" would calm the Cold War's increasing acrimony, articulated clearly why it wouldn't.

"Two opposing ways of life are ranged against each other," he said. "These cannot be reconciled and we must accept the fact that this great division of the world may last."

That was the essence of the Cold War that lasted until 1990 — not, as liberals often claimed, a lack of détente or excessive military spending or (as Jimmy Carter notoriously claimed) an "inordinate fear of Communism" by Americans. As long as both camps — the totalitarian communists of the Soviet empire and the capitalist democracies of NATO — were determined to prevail, peace remained impossible.

According to data cited by Beckley, there have been 27 great-power rivalries since 1816. Those struggles lasted, on average, for more than 50 years and more than two-thirds of them "culminated in war, with one side beating the other into submission." Ruthless though it may sound, crushing an enemy's will to prevail is the best and surest way to end a conflict and establish peace.

It was not summit meetings, international conferences, peace movements, concessions for the sake of appeasement, or the League of Nations that finally put to rest the decades-long Anglo-German rivalry and the even more ancient enmity between France and Germany. It was the devastating defeat of Germany by the Allies in 1945, and the end of Berlin's aim of ruling Europe, that paved the way for Germany's transformation into a free, stable, and peaceable democracy.

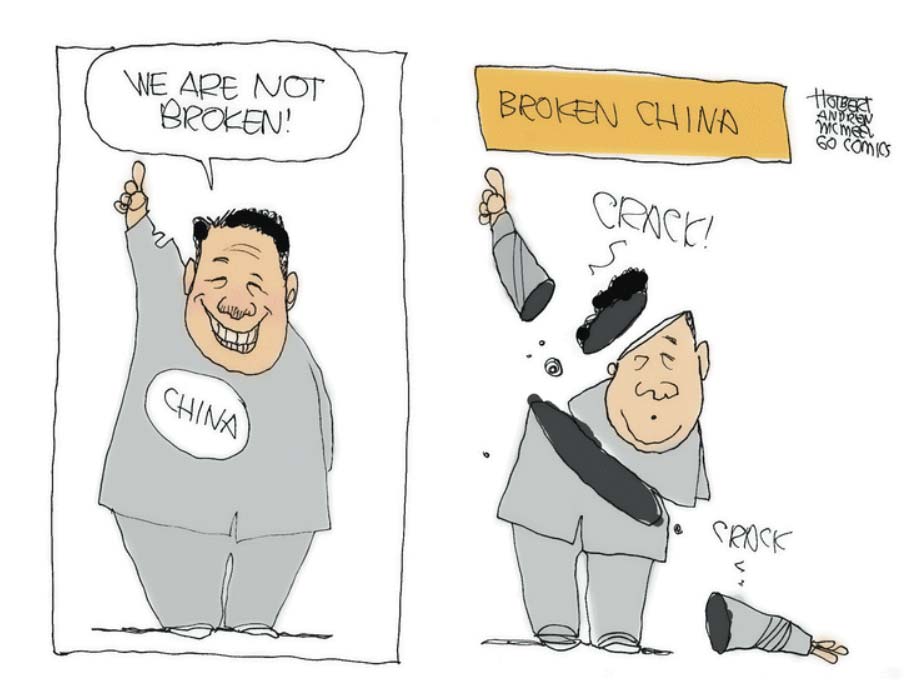

Beckley's essay is written in the context of the present US-China rivalry. He notes that multiple analysts have been voicing the opinion that "if only the United States would talk more to China and accommodate its rise, the two countries could live in peace." In their view, there is no need for Washington and Beijing to clash — and risk a nuclear war — over Taiwanese autonomy, a military buildup in East Asia, the enslavement of Uyghur Muslims, or the theft of US technology. The rivalry between the two countries could be ratcheted down — so the advocates of engagement argue — if only the American people and their leaders would be more sensitive to Chinese concerns and less susceptible to what one critic calls "hysteria and alarmism" about the Chinese Communist Party.

But that's a fantasy. China is not interested in winding down or compromising away its conflict with the United States. It is interested in getting what it wants. And what Beijing wants, Beckley, writes is for "the United States to end arms sales to Taiwan, slash the overall US military presence in East Asia, share US technology with Chinese companies . . . [and] stop promoting democracy in China's neighborhood." More fundamentally, it wants to establish hegemony over its part of the world and to not be hectored about human rights.

As a result, all signs point to an enduring rivalry between the two great powers. As with the Soviet Union during the Cold War, the US focus must be on containing China's aggression. That makes it much more important to deter China's bad behavior than to reassure Beijing of America's goodwill. For example, there should be no ambiguity whatsoever about Washington's determination to defend Taiwan from any Chinese attack. US weapons should be pouring into the island and the American military presence in the region should be beefed up — now, not when an invasion is imminent.

In November 1993, a meeting of Chinese foreign- and military-policy specialists produced a detailed report that began: "Whom does the Communist Party of China regard as its international archenemy? It is the United States." For decades, the Soviet Union saw the United States in the same light. But the US-Soviet Cold War didn't last forever. The US-China rivalry need not either.

Congress and the White House should be pursuing a strategy toward China modeled on the Reagan administration's winning playbook against the USSR: Keep up the pressure until the communist system is undermined by its own inherent weaknesses. As things stand, Chinese growth is stalling, its population is shrinking, its debt is soaring, and its trade is being impeded by restrictions imposed from abroad. What is called for now is not jaw-jaw. It is for the US to stay the course, maintaining its deterrence and unapologetically defending Western interests, until victory is achieved.

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe, from which this is reprinted with permission."

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author