Howard Broadman donated a kidney to a patient who needed one now. In exchange, his grandson Quinn will receive a kidney when he is old enough for the transplant he will require.

Howard Broadman donated a kidney to a patient who needed one now. In exchange, his grandson Quinn will receive a kidney when he is old enough for the transplant he will require.

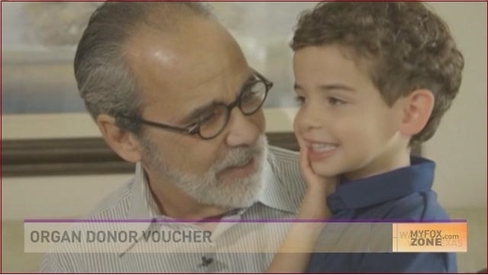

Howard Broadman is a retired California judge with an active private practice as an arbitrator. He is also the grandfather of a little boy named Quinn, who was born with serious kidney problems. In time Quinn will require regular dialysis to stay alive until he's eligible for a kidney transplant. Broadman would gladly have donated one of his own kidneys to save his grandson's life. But Quinn is still too young for a transplant — and by the time he's ready, his grandfather will be too old.

So Broadman, together with transplant surgeon Jeffrey Veale, proposed an arrangement to the UCLA Medical Center: He would donate a kidney to a patient who needs one now, in exchange for a "voucher" that Quinn can use when he needs a transplant in the future. UCLA not only agreed to the proposal, it inspired 10 other hospitals around the country to offer the same arrangement to potential kidney donors: Save a stranger's life today, so your loved one's life can be saved in the future.

Veale hopes that if Broadman's brainchild spreads, the waiting list for kidney transplants may at last begin to shrink. For years that list has been growing, and the death toll from kidney failure with it.

The numbers are heartbreaking. As of January, according to the National Kidney Foundation, nearly 101,000 Americans were waiting for a kidney transplant, and more than 3,000 patients were being added to the waiting list each month. In 2014, approximately 17,000 kidney transplants were performed in the United States. But almost 4,800 patients died while waiting for a kidney that never came, and another 3,700 grew so sick that they were no longer eligible for a transplant.

Every day, another 13 Americans die for lack of a lifesaving kidney. Yet if just one-half of 1 percent of the nation's adults became living kidney donors, as UCLA's transplant staff points out, the US waiting list for kidneys would be eliminated 15 times over.

Most transplanted organs currently come from the bodies of people of who have recently died; in 2014, there were about 7,800 such donors, yielding 11,570 usable kidneys. If more Americans registered as organ donors — or if the United States were to emulate Spain's "opt-out" system, which presumes that individuals consent to donate their organs at death unless they specify otherwise — thousands of additional lives could be saved each year.

But cadaveric organ donation will never be enough. "Relatively few people die in ways that leave their organs suitable for transplantation," writes Sally Satel, a physician and scholar at the American Enterprise Institute (and herself the recipient of a donated kidney). And organs donated by living donors last, on average, five to 10 years longer than those transplanted from a deceased donor.

The need for more living donors has never been greater. Broadman's blessed innovation will help, by providing an incentive in the form of a kidney voucher for a family member in the future. But judging from the minuscule number of living donors in this country — only 5,500 Americans donated a kidney in 2014 — it will take more concrete incentives to get the number up.

Unfortunately, the 1984 National Organ Transplant Act makes it a crime to reward anyone with "valuable consideration" for agreeing to donate a kidney or other organ. Altruism alone is supposed to motivate organ donations. Lawmakers feared that offering financial incentives to donors or their families would be demeaning, turning human organs into mere commodities to be bought and sold. Others have expressed concerns about the poor being exploited, relinquishing an organ not from the goodness of their hearts, but from a desperate need for cash.

Against those theoretical sensibilities is the brutal outcome of our existing organ transplant policy: More than 100,000 sufferers condemned to dialysis, agonizing waits for a kidney to become available, and thousands of preventable deaths every year.

Some people will always be motivated to donate an organ — or do any good or useful thing — for altruistic motives. Far more will be motivated by material rewards. Successful kidney transplantation requires the services of surgeons and anesthesiologists, nurses and orderlies, clerical and pharmaceutical staff. None of them is expected to volunteer their efforts, and no one suggests it is demeaning or immoral for them to be paid. Yet federal law demands that the most crucial transplantation service of all — the donation of the organ that preserves a life — be provided out of sheer good will. Until that changes, Americans who could be saved will go on dying.

Economists have frequently argued that a liberalized market in organ transplants would rapidly increase the supply of kidneys. Medical researchers have reached similar conclusions. A study published last year in the American Journal of Transplantation calculated that if the government were to begin paying $45,000 for each donated kidney, taxpayers would end up saving $12 billion annually in public expenditures. And for society and the economy as a whole, the study estimated, the "net benefit" from saving so many lives and reducing the need for dialysis "would be about $46 billion per year, with the benefits exceeding the costs by a factor of 3."

Incentives don't have to take the form of cash payments. Satel has proposed reimbursing organ donations with in-kind rewards, "such as a contribution to the donor's retirement fund; an income tax credit or a tuition voucher; lifetime health insurance; a contribution to a charity of the donor's choice; or loan forgiveness." She notes that even the American Medical Association has called for testing the effect of material incentives on organ donation rates.

It may be hard for some to shake the sense that there's something repellent about paying people to give up a kidney. The alternative is for thousands of Americans to die pointlessly each year. Isn't that more repellent?

Comment by clicking here.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author