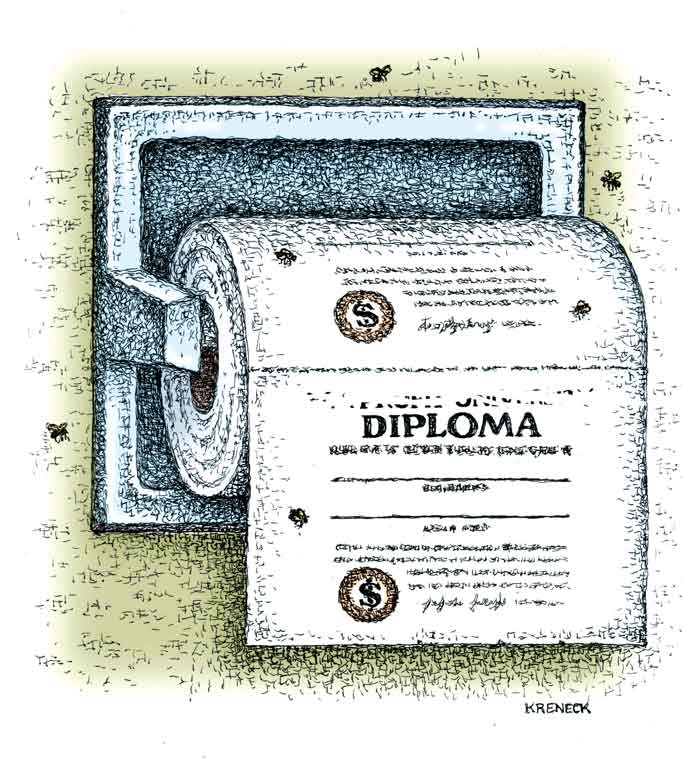

The dumbing down of American education proceeds apace. It is no secret that students in most schools today are expected to learn less, read less, and write less than was expected of students in earlier generations. With a dwindling number of exceptions, they are also no longer expected to pass high-level tests in order to prove that they mastered the material they were supposed to learn.

When Massachusetts voters last fall approved a ballot measure abolishing the longstanding requirement that students had to pass a standardized 10th-grade test in math, science, and English as a condition of getting a high school diploma, they joined what has become a nationwide stampede toward ever-lower standards. As recently as 2012, high school seniors in at least 25 states were still required to pass a test demonstrating proficiency in reading, writing, and math in order to graduate. Now only six states — Florida, Louisiana, New Jersey, Ohio, Texas, and Virginia — still hold kids to that standard. (New York will end its Regents exam graduation requirement in 2027.)

The Massachusetts test, known as MCAS, wasn't a cakewalk; it called for a fair amount of time, study, and classroom preparation. But 96 percent of students passed the tests, nearly all on their first try. The impact of the MCAS requirement on education in Bay State schools spoke for itself. In the 1980s, the quality of public schools in Massachusetts was no better than mediocre. But with the passage in 1993 of an education reform law — a key component of which was standardized testing — the state's education system improved dramatically; before long, Massachusetts had the highest-performing public education system in the nation.

Yet despite those standout results, Bay State voters couldn't resist joining the flight from high standards. The Massachusetts Teachers Union — which prioritizes the interests of teachers over the interests of students — spent more than $16 million on a successful campaign to scrap one of the great public policy successes in Massachusetts history.

It isn't only graduation tests that have been diluted or abolished. Across the country activists argue that standardized tests like the SAT are too stressful, too discriminatory, or simply irrelevant — and should therefore be made easier or dumped altogether.

Yet when one looks at what students a century ago were expected to master in order to graduate from high school — or in some cases to get into high school — today's complaints about standardized tests seem almost comical by comparison. The historical record makes one thing clear: Today's test-takers don't know how easy they have it.

Consider some questions from the final exam administered to 8th-grade students in Salina, Kansas, in 1895. The five-hour test — which covered grammar, arithmetic, American history, orthography, and geography — would defeat the vast majority of today's high school seniors, let alone students who hadn't yet entered 9th grade.

Here are a dozen of the questions those Kansas teens were expected to answer:

• What are the following? Give examples: trigraph, subvocals, diphthong, cognate letters, linguals.

• Use the following in sentences: cite, site, sight; fane, fain, feign; vane, vain, vein; raze, raise, rays.

• A wagon box is 2 feet deep, 10 feet long, and 3 feet wide. How many bushels of wheat will it hold?

• Find the interest on $512.60 for 8 months and 18 days at 7 percent.

• What is the cost of 40 boards, 12 inches wide and 16 feet long, at $.20 per inch?

• What are the principal parts of a verb? Give principal parts of do, lie, lay, and run.

• Who were the following: Morse, Whitney, Fulton, Bell, Lincoln, Penn, and Howe?

• Name the events connected with the following dates: 1607, 1620, 1776, 1789, and 1865.

• Why is the Atlantic Coast colder than the Pacific in the same latitude?

• Name all the republics of Europe and give capital of each.

Too tough? Tell that to the New Jersey kids who sat down to be tested a decade earlier. In 1885, the Jersey City High School exam covered algebra, arithmetic, geography, grammar, and US history. Here are five questions from the geography section:

• What is the axis of the earth and what is the equator?

• What is the distance from the equator to either pole in degrees and in miles?

• Name four principal mountain ranges in Asia, three in Europe, and three in Africa.

• Name the states on the west bank of the Mississippi and the capital of each.

• Name the capitals of the following countries: Portugal, Greece, Egypt, Persia, Japan, China, Canada, Cuba.

And here are five from the history portion:

• Name the thirteen colonies that declared their independence in 1776.

• Name three events of 1777. Which was the most important and why?

• What caused the War of 1812?

• Who was president during that war?

• Name four Spanish explorers and state what induced them to come to America.

These weren't impossible questions. They weren't pitched to the smartest kids in the class. On the contrary — they covered information that most students of normal ability could reasonably be expected to master. And they reflected an expectation that students leaving school would be literate, numerate, and have a working knowledge of their nation's history and the principal features of the globe.

There is no such expectation today. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress — commonly referred to as "the nation's report card" — the reading and comprehension skills of American kids are worse than they have ever been.

"The percentage of eighth graders who have 'below basic' reading skills according to NAEP is the largest it has been in the exam's three-decade history — 33 percent," The New York Times reported in January. "The percentage of fourth graders at 'below basic' was the largest in 20 years, at 40 percent…. [S]tudents who score below basic cannot determine the main idea of a text or identify differing sides of an argument."

Given such terrible results, you might imagine that policymakers and parents would be pressing urgently to raise academic standards and insisting that teachers and school administrators meet them. But nearly all the movement is in the other direction.

Especially disturbing is the way the SAT — for decades a consistent barometer of academic readiness and the single most reliable predictor of how a student will perform in college — has been watered down by the College Board.

To begin with, the test is now administered in a digital format that calibrates the difficulty level of the questions to the performance of the test-taker.

"If a student struggles in the first section, the test adjusts to become easier; if they excel, it becomes harder," the Manhattan Institute's Vilda Westh Blanc and Tim Rosenberger recently wrote in National Review. In other words, the SAT now actively "penalizes preparedness and effort, effectively punishing those who rise to the challenge while coddling those less prepared." The College Board defends the new format by noting that 80 percent of students feel less stressed while taking the new digital test. But who ever thought sitting for the SAT was intended to be a stress-free experience? Turning it into one strips away the ability to determine something important about potential college students — namely, how they perform under pressure.

There are other changes. The SAT now lasts two hours instead of three. Students are allowed to use calculators for all math questions. Passages in the reading section are limited to no more than 150 words — far shorter than the 750-word excerpts that were typical until now. And linked to each reading is only one question, not several.

The upshot is that students are no longer required to parse complex or historically significant texts. Instead, the reading assignments are being made almost childishly easy. "Instead of engaging with the great works of literature and foundational documents that have shaped Western civilization, students are asked to interpret snippets akin to tweets or memes," Blanc and Rosenberger observe. If students are never required to read anything more challenging than short texts, how will they ever learn to wrestle with ambiguity, to shape thoughtful arguments, or to make sense of complex sentences and difficult syntax?

Amid the current vogue for weakening tests and lowering expectations, it is worth asking: Why did educators a century (or more) ago set such high standards? Perhaps it was because they saw education not just as a means to get a job, but as a moral and civic duty — a way to form responsible citizens who understood their history, could articulate their thoughts, and would therefore be better able to contribute to society.

Testing was viewed as a tool of accountability — not as the enemy of learning, but as its natural culmination. It sent the message that knowledge mattered and that everyone, regardless of background, could rise to the occasion.

The cultural context then was very different. Students understood that passing the eighth-grade exam might be their only chance to prove themselves before entering the workforce. Education was precious; exams were taken seriously; kids were not infantilized.

Lowering standards may feel like a kindness in the short term, but it comes at a steep cost: a diminished sense of what students are capable of achieving and a weaker intellectual foundation for society. The young Americans of 1895, often sitting in one-room schoolhouses, did not have smartphones, calculators, Google, or AI — but they rose to demanding expectations and built a thriving nation.

Today's students, with far more resources at their disposal, should not be sold short. The school-leaving tests of the past were rigorous not out of cruelty, but out of respect. Good educators, then as now, knew that if you hold students to high standards of learning, the odds rise that they will meet them. If you worry more about their self-esteem or stress or "diversity," they're apt to learn less.

Are you astonished that teenagers a century ago could handle questions like the ones above? Don't be. The real shocker isn't that high school students then could meet such a challenge. It's that students today are no longer expected to.

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe, from which this is reprinted with permission.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author