Insight

Without compromise, American democracy has no future

The Intersection of faith, culture, and politics

Tuesday

February 24th, 2026Insight

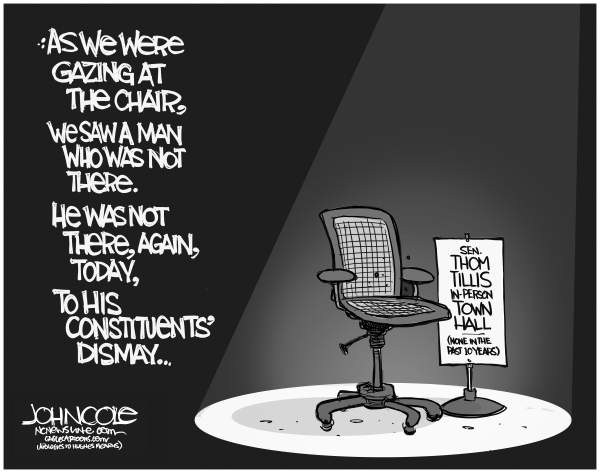

Two of Congress's least dogmatic Republicans announced last week that they will not run for reelection when their current terms expire in 18 months. Senator Thom Tillis of North Carolina and Representative Don Bacon of Nebraska are staunch conservatives who usually vote with their party. But they also believe in bipartisan collegiality, in forming alliances across the aisle, and in making up their own minds. In today's GOP, that makes them radioactive.

When Tillis declined to blindly support the so-called Big Beautiful Bill without changes, President Trump slammed him as "a talker and complainer" and vowed to back a primary challenge to him next year. That was enough to convince Tillis that two terms in the Senate were enough.

"In Washington over the last few years," he said on June 29, "it's become increasingly evident that leaders who are willing to embrace bipartisanship, compromise, and demonstrate independent thinking are becoming an endangered species."

The following day, Bacon announced that he'd also had enough of the intolerant partisanship dominating Congress. The former Air Force brigadier general, describing himself as "a proponent for old-fashioned Ronald Reagan conservative values," is a vocal supporter of US military aid to Ukraine and has criticized Trump's attacks on Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky. Bacon also opposed Trump's sweeping trade war and introduced legislation to curb the president's power to impose tariffs. For that he was blasted by Trump as a "rebel Republican" who just "wants to grandstand."

Tillis and Bacon aren't rebels. They just don't believe their job is to elevate hardline ideological rigidity above all other considerations. In that sense they are like former Senators Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia, two Democrats who likewise found themselves demonized for occasionally making common cause with members of the opposing party. Last year, they too chose not to run for reelection.

Of all the developments that have sickened American politics in this generation, the abandonment of democratic civility and the resulting hostility to compromise are the most toxic. The virtues of moderation and magnanimity, the willingness to engage respectfully with others' views, the assumption that individuals with contrary opinions may be wrong but are not evil — without these, our political institutions cannot function. The first and most vital task of liberal democratic politics is to accommodate strong differences without tearing society apart. But that becomes impossible when conciliation is regarded as treachery — and when politics stops focusing on persuasion and debate and becomes obsessed instead with defeating enemies by any means necessary.

Granted, politics ain't beanbag. The United States has never suffered from a shortage of harsh rhetoric. Some political activists have always been tempted to confuse passionate disagreement with personal enmity.

Yet compromise has been the lifeblood of the American experiment from its earliest days. The very possibility of self‑government is grounded in the presumption that citizens with intensely held but divergent views can find ways to cooperate. The American founders knew perfectly well that there would always be deep disputes over principles, tactics, means, and ends. That is why they regarded compromise not as a necessary evil but as an essential element of our constitutional system.

"Those who hammer out painful deals perform the hardest and, often, highest work of politics," the American thinker Jonathan Rauch wrote in a 2013 essay in National Affairs. "They deserve, in general, respect for their willingness to constructively advance their ideals, not condemnation for treachery."

In "Profiles in Courage," John F. Kennedy expressed something similar: "Compromise does not mean cowardice," he wrote. "Indeed it is frequently the compromisers and conciliators who are faced with the severest tests of political courage as they oppose the extremist views of their constituents." I wonder what JFK would have made of today's venomous political climate, in which "compromise" is too often wielded as a slur and the search for common ground is disdained as capitulation.

America's independence holiday is a good time to remember that some of this nation's greatest achievements emerged from political give‑and‑take, not from unilateral assertions of power.

The Constitution itself was born of compromise. At the convention in 1787, delegates were deadlocked between a population-based legislature (favored by large states) and one that would treat all states equally (favored by small states). Had the impasse not been broken by what was later called the Great Compromise — a bicameral Congress with proportional representation in the House and equal representation in the Senate — the convention would have collapsed and the fragile confederation of states might never have endured.

American progress has depended time and again on the ability of political leaders to transcend their partisan, sectional, or ideological loyalties and reach a compromise all sides could live with.

Consider the bargain struck in 1790 between Alexander Hamilton of New York and Virginia's Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Hamilton wanted the federal government to assume all state debts, which would amount to a dramatic expansion of national power. That prospect alarmed Southern leaders like Jefferson and Madison — but they agreed not to derail the plan in exchange for locating the new national capital on the Maryland-Virginia border instead of in one of the major commercial centers of the North. Though each side had to swallow a bitter pill, the deal achieved two vital ends: national creditworthiness through debt assumption, and a seat of government accessible to both North and South. And it showed that even foundational questions about the scope of federal power could be resolved through negotiation rather than force.

Congress similarly chose compromise over caustic stalemate in 1964, with a Civil Rights Act that combined Southern concessions on federalism with Northern demands to outlaw segregation. The law was far from perfect, but it transformed American society and politics. It passed despite the opposition of hard-core segregationists, thanks to a bipartisan coalition hammered together by President Lyndon Johnson and Senator Everett Dirksen, the Republican minority leader — proof that compromise, when linked to moral conviction, can dismantle entrenched injustice.

To mention one more, recall the 1997 budget agreement. When Republicans under Newt Gingrich won control of the US House for the first time in decades, their "Contract With America" seemed flatly irreconcilable with President Bill Clinton's priorities. Yet after a bruising standoff, party leaders on both sides crafted a budget deal that capped spending, reformed welfare, cut taxes — and accomplished the astonishing feat of balancing the federal budget. For the next several years, there was no deficit spending: The government ran surpluses. It was one more illustration of how ideological opponents, if they are motivated to do so, can find ways to compromise.

None of this is to suggest that all compromises are good. That would be as ridiculous as insisting that any compromise is bad. The point, rather, is that without the ability to compromise — and without the civility and mutual respect that make that possible — our democratic republic cannot survive. Maybe we've already crossed that point. Is there any reason to be optimistic about a Congress in which fanatics like Marjorie Taylor Greene and Bernie Sanders flourish while thoughtful legislators such as Thom Tillis and Kyrsten Sinema are marginalized until they resign?

In "Miracle at Philadelphia," her classic history of 1787, Catherine Drinker Bowen wrote: "In the Constitutional Convention, the spirit of compromise reigned in grace and glory. As Washington presided, it sat on his shoulder like the dove. Men rise to speak and one sees them struggle with the bias of birthright, locality, statehood. ... One sees them change their minds, fight against pride, and when the moment comes, admit their error."

What would have happened if those men hadn't been able to reason together — if they had abandoned all efforts to persuade and had resorted instead to invective and intimidation? The American experiment might have ended before it even got off the ground. If today's leaders continue to scorn compromise and civility, ours may be the generation that brings it crashing back to earth.

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe, from which this is reprinted with permission.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

© 2026 Boston Globe