Gannett, the nation's largest newspaper chain, wants its publications to break with the practice of endorsing candidates in presidential and congressional elections. According to The Washington Post, a committee of editors convened by Gannett made the recommendation in April, updating a 2018 planning document that urged papers to "endorse less, if at all," and said it was "time to get out of presidential endorsements."

They'll get no argument from me. I have long been of the view that newspaper endorsements generally matter far less to voters than editors and publishers imagine, that it isn't the role of news outlets to take sides in an election, and that doing so only gives readers cause to doubt their objectivity and credibility.

In the buzz that followed Oprah Winfrey's endorsement of Barack Obama's presidential run in 2007, the Pew Research Center asked voters about the impact of potential endorsements by various celebrities and institutions.

Pew found that only 14 percent of voters said they would be more likely to support a candidate endorsed by their local newspaper — while another 14 percent said they would be less likely to support that candidate. The overwhelming majority, 69 percent, said the paper's endorsement would have no influence on their vote at all.

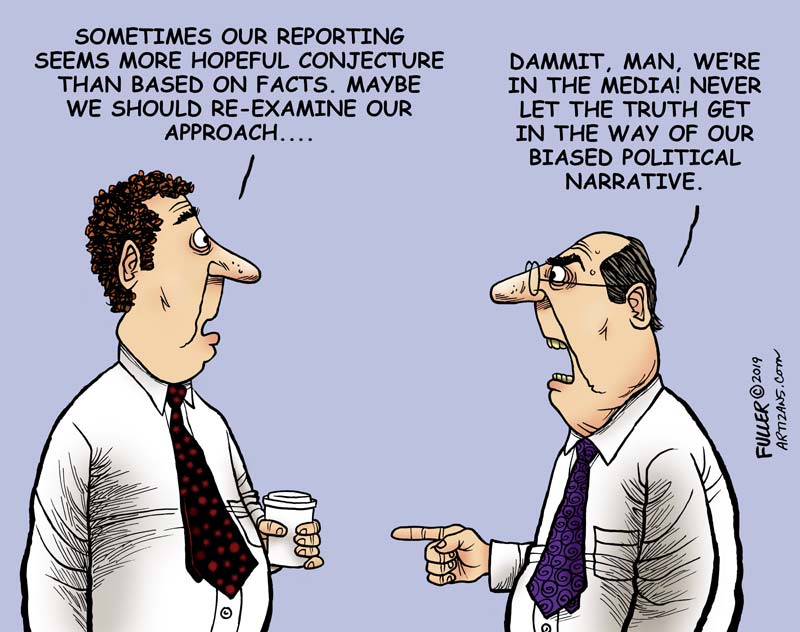

Americans' confidence in the fairness and accuracy of news organizations is at or near an all-time low. A large majority of the public believes that the media are politically biased. What sense does it make for newspapers to reinforce those beliefs by proclaiming a loyalty to one side in a political campaign? Inevitably, many readers will assume that if a newspaper endorses a candidate during an election campaign, it will tilt its news coverage to favor that candidate.

A few newspapers have a longstanding policy against endorsements. The Wall Street Journal last gave its imprimatur to a presidential hopeful in 1928, when it endorsed Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover over New York Governor Al Smith. A vote for Hoover, the paper said, was "the soundest proposition for those with a financial stake in the country."

But when the onset of the Great Depression made it clear that Hoover had been the wrong man for the job, the Journal learned its lesson. It has never again endorsed any candidate. "We don't think our business is telling people how to vote," a Journal editorial explained in 1972.

In recent years, a number of papers have adopted the Journal's approach. The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Arizona Republic, and the Cincinnati Enquirer are among those that no longer endorse candidates.

Some other papers, including the Chicago Sun-Times and The Salt Lake Tribune, have reorganized as nonprofits and are now barred by federal law from explicitly supporting or opposing candidates. I think every newspaper ought to follow suit. There is no evidence that readers want newspapers telling them whom to vote for, and considerable evidence that they don't.

Let newspapers continue to interview candidates. Let them publish transcripts or post the video of those conversations. Let them editorialize on candidates' proposals, track records, and political ideas. Let them publish the views of columnists from across the political spectrum.

But don't tell readers who should get their vote. Politicians don't endorse newspapers. It's time newspapers stopped endorsing politicians.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author