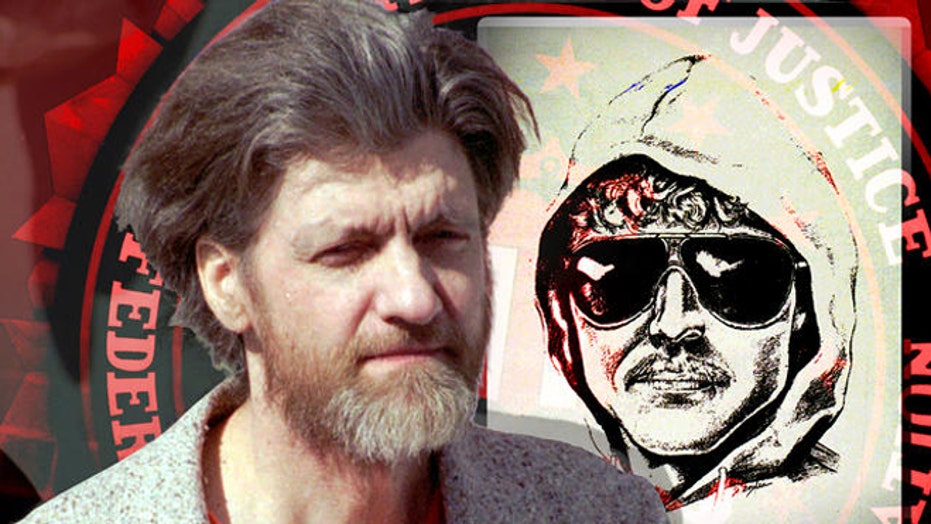

Their paths never crossed. They came from utterly different backgrounds. But Theodore "Ted" Kaczynski, known as the Unabomber, and James "Whitey" Bulger, the South Boston gangster, had a few key things in common.

Both men were psychopathic murderers, responsible for killing, maiming, or terrorizing scores of victims during their criminal careers. Both evaded the FBI for years and were found only after lengthy manhunts. Both were eventually convicted and sentenced to multiple life terms. Both died of unnatural causes — Bulger after a savage beating in 2018 at the federal penitentiary in Bruceton Mills, W.Va., and Kaczynski at the federal prison in Butner, N.C., by suicide on Saturday.

In the days since Kaczynski's death, I have been thinking about something else the men had in common. Each had a younger brother who found himself in possession of information that could enable his homicidal older sibling to be brought to justice.

But that's where that similarity ended.

When David Kaczynski in 1995 read a 30,000-word manifesto written by someone claiming responsibility for the Unabomber's terror spree, he recognized his brother's style of writing and fanatical tone. David cared deeply about Ted, a brilliant mathematician who had gradually become a recluse, severing contact with his family and moving to a shack in the Montana wilderness. From an early age, David had understood that his brother, whom he idolized, wrestled with psychological demons. When their mother at one point pleaded with David to never turn his back on his brother, he assented. "I promised Mom that I would never abandon Ted," he later wrote.

But then he found himself confronted with evidence that his brother had become a homicidal monster, and realized that his obligation to keep others from being hurt overrode the ties of family loyalty. He contacted the FBI, providing the agency with letters and documents written by Ted. His information led to the Unabomber's arrest at his Montana cabin, where authorities found a bomb ready for mailing and a hit list of potential victims.

Whitey Bulger's younger brother made a very different choice.

It was in the same year of 1995 that Boston's murderous crime boss, tipped off that he was about to be indicted for his long reign of terror, fled from Boston. For 16 years, he would remain on the run, listed on the FBI's Ten Most Wanted list. In all that time, his younger brother William — the powerful president of the state Senate and then the president of the University of Massachusetts — refused to condemn Whitey's crimes. When his fugitive brother contacted him by phone, he kept it a secret. Years later, he admitted to a federal grand jury that he had never urged Whitey to turn himself in because, he said, "I don't think it would be in his interest to do so." In fact, he sneered, "It's my hope that I'm never helpful to anyone against him."

In David Kaczynski's moral code, no consideration outweighed the obligation to stop his brother before he maimed or murdered someone else. Bill Bulger lived by a different hierarchy of values, one in which nothing, not even the saving of human life, mattered more than tribal loyalty.

There were prominent voices that derided David Kaczynski for going to the FBI.

"No one will ever wholly trust someone who turned in his own brother," the novelist and screenwriter Michael Ventura wrote in the Los Angeles Times. The prominent radio talk host (and convicted Watergate felon) G. Gordon Liddy excoriated Kaczynski as a "snitch" who "violate[d] the taboo against turning on one's family." David Letterman mocked him as the "Unasquealer."

Conversely, there were leading figures who sang Bill Bulger's praises for showing more allegiance to his evil brother than to Whitey's past and possible future victims, or to the law he had repeatedly sworn to uphold. "My respect and admiration for President Bulger is stronger than ever," gushed a servile Grace Fey, the then-chair of the UMass board of trustees. Former governor William Weld, who was once a federal prosecutor, issued a revolting statement hailing Bill Bulger as "a man of honesty, integrity, compassion."

In the end, all that remains to most of us is the reputation we fashion during our lives. David Kaczynski is best known today for the moral decency he showed when faced with an excruciating personal dilemma. Bill Bulger, once so feared and fawned over, is living out his days in ignominy, remembered for his silence when a man of honor would have spoken.

The Unabomber and Whitey Bulger were vile human beings. But one of them, at least, is survived by a man of good character.

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe, from which this is reprinted with permission."

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author