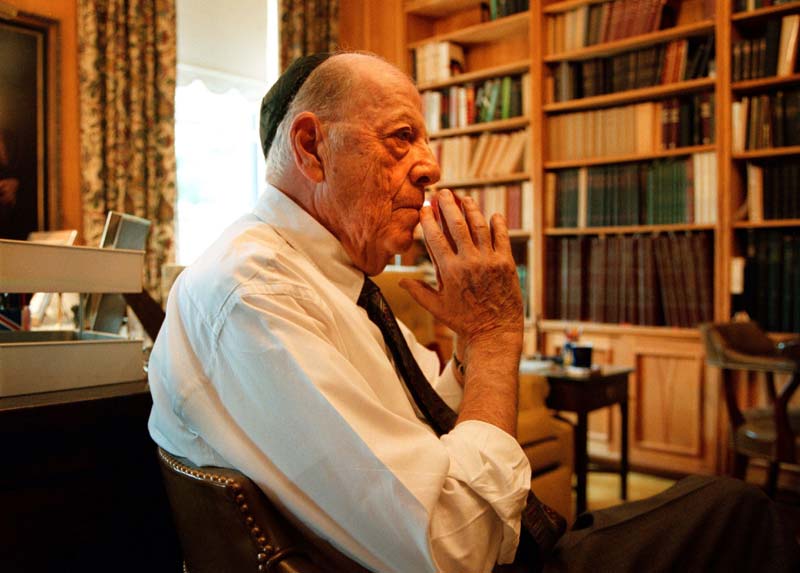

James A.Parcell for The Washington Post

James A.Parcell for The Washington Post

I met him when I was 16, and didn't even realize it at the time. Here's how it happened.

That summer I had been reading Marjorie Morningstar , Wouk's novel about a beautiful teenager who dreams of becoming an actress, and along the way discards the traditional values, norms, and constraints of her middle-class Jewish upbringing. The book had been a smash bestseller when it was published in 1955, landing Wouk on the cover of Time magazine.

I had discovered it 20 years later, in the library of my Orthodox synagogue in Cleveland. I'm not sure what it was doing there, inasmuch as the abandonment of religious observance in favor of more worldly and unbuttoned lures was one of the book's themes. Be that as it may, it more than held my interest --- especially its description of the "necking" and "furtive sex fumbling" of Marjorie's love life, a subject that for me was then wholly theoretical and utterly enthralling.

For all I know, I'm the only person who ever read Marjorie Morningstar in a synagogue on Sabbath afternoons. While my father studied Talmud in a class that was taught in Yiddish, I was preoccupied with Wouk's vivacious heroine. Reading at the rate of a chapter or two each Saturday, it took a while to get through the book. I finished it just in time: one day before I was due to head off to college in Washington, D.C.

We drove there -- my parents, my siblings, and I -- in the family station wagon, arriving in Washington on Sunday evening and checking into a motel. On Monday morning, my father's first order of business was to attend morning prayers, and he and I made our way to Kesher Israel Congregation, an Orthdox shul at 28th and N streets in Georgetown.

Kesher was within walking distance of my George Washington University dormitory, and it would become my regular place of worship during my college years. But on that first Monday morning, of course, I didn't know anyone, so I was grateful when one of the regulars -- a courtly older man with an oblong face and an engaging smile -- came over after the service to say hello to my father and me. Upon learning that I was a new student in town and would be at Kesher often, he made a point of introducing me to the rabbi and several of the regular worshippers. "And my name," he said genially, "is Herman Wolf."

Well, that's what I thought he said.

It took a couple of weeks before I figured out that the genial gentleman was Herman Wouk --- whose famous book I had finished reading less than 48 hours earlier. I was mortified as I imagined what he must have thought when the mention of his name produced not a flicker of recognition from the new freshman he had reached out to so welcomingly. (Another brainless GW dolt. Probably never cracked a book in his life.) By that point it was too late to tell him that I had simply misheard him, and to gush about Marjorie Morningstar. Or maybe it wasn't, but I was too intimidated to know better.

Nor did I gush to Wouk about The Caine Mutiny. Published nearly 30 years earlier, that had been his first great success, a World War II masterpiece for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1951. I remember reading it when I was 17 or 18, but couldn't really say how much I got out of it. It wasn't until years later, long after college was behind me, that I read The Caine Mutiny for the second time, and understood far more about what makes it such a great novel. Its themes resonated then in ways they hadn't when I was younger: the stubborn paranoia of Captain Queeg, for instance, and the maturation of the callow Willie Keith, and the indispensability of the Navy regulars who stood watch for years as so many others pursued more lucrative and glamorous paths.

In any case, by the time I got around to reading The Caine Mutiny, it was practically ancient history. Wouk had moved to Washington to work on his two subsequent World War II novels, massive and gripping: The Winds of War and War and Remembrance . The latter came out a few months before I graduated, and for the life of me I don't know why I felt too shy to ask him to inscribe the copy I had bought. Perhaps all the attendant publicity kept him out of town on a book tour for long spells. Perhaps it was because I encountered him exclusively at the synagogue --- the place where he came to pray, not to be importuned by autograph-seekers.

But if I never got Wouk's signature on any of the books he wrote -- the list is a long one -- I have other things to remember him by.

During services one morning at Kesher, the prayers were being led by someone who was mangling the words almost as badly as he was wrecking the simple tune. At one point I caught Wouk's eye and grimaced with distaste. He came over to me a minute or two later. "In the Navy we used to have an expression," he murmured. "Don't shoot the piano player; he's doing the best he can."

Another story:

Wouk had a dog, a German shepherd, as I recall, with the perfect name for an author's pet: He called it Barkis, after a character in David Copperfield --- a coachman whose unfailing message was, "Barkis is willin'." He used to bring the dog with him to synagogue sometimes on Saturday, a thing I've never seen anyone else do, in any synagogue anywhere.

Barkis would lie quietly in the little vestibule downstairs, snoozing while the longish Sabbath prayers were underway one flight up. Normally I was upstairs myself until the proceedings ended, but on a couple of occasions I happened to come down early. On both occasions I was in that vestibule when the congregation began to sing "Aleinu," a hymn that is one of the last parts of the liturgy. The people stand when "Aleinu" is sung --- and when Barkis heard the melody, he stood too, wide awake. Apparently he had learned to associate the song with his owner's imminent departure. Or maybe, like some shul -goers, Barkis was willin' to stay to the end of the service, but not a minute longer.

But none of this is why I say that Herman Wouk forever transformed my life.

In 1959, with The Caine Mutiny and Marjorie Morningstar and a few other novels under his belt, Wouk startled his agent by sending him the manuscript of a book quite unlike anything he had written before. Its topic was religion, it bore the title This Is My G od (the phrase comes from Exodus 15:2 ), and it was an explanation of the modern Orthodox Judaism to which he was and is deeply committed. Wouk had brought all his gifts as a storyteller to this exposition of his faith; what he produced was learned, warm, and sincere, an exploration of the beauty of Jewish life that managed to be both intellectually rigorous, yet broadly appealing.

As Wouk would recollect much later in the brief literary memoir he published on becoming a centenarian, his publisher was "obviously disconcerted by this religious aberration of a bestselling author." There was no precedent for such a book, and it was expected to attract little interest beyond Wouk's existing fan base. So Doubleday, the publisher, ordered only a modest first printing of a few thousand copies. Whereupon "This Is My G od skyrockets off," Wouk recalled, still clearly delighted, "taking second place in nonfiction sales for half a year to the playwright Moss Hart's lively memoir, Act One."

All these years later, This Is My G od is still in print; according to Amazon, its sales rank in the Top 10 among books on Jewish theology and very nearly as high among books on Jewish life. Here is a tiny excerpt, from Wouk's discussion of prayer:

"The first tractate of the Talmud, Benedictions . . . lays down the rule that one should bless the Creator for every good in this world; and it even contains a remarkable blessing on evil news. Perhaps the most startling passage in it, for a modern reader, is an open authorization to pray in English; that is, in any language one understands. The popular notion is that English prayer is a shattering heresy. Our common law allowed it two thousand years ago.

Despite that, the Jews have always clung to a Hebrew liturgy. In previous times it might have caused less trouble and disaffection if the prayers had been in Greek, Aramaic, Latin, Egyptian, Arabic, Spanish, French, Turkish, German, Polish, or Russian. But the community, by a continuing mass instinct, has held to the Scripture tongue. That instinct is asserting itself today in the United States, in the Reform and Conservative movements, which year by year bring back more Hebrew into their devotions.

I have no idea when I first came across This Is My G od. But I remember with perfect clarity the first time I bought a copy to give someone else.

She was a woman I had met in Massachusetts political circles. As we became friendly, she grew curious about my religious beliefs. She had been raised in the Methodist church in the rural reaches of northern New York State; my Orthodox Jewish background piqued her curiosity. So I answered her questions, which sparked more questions. As we browsed together in a bookstore one day, my eye fell on the Religion section. I bought This Is My G od and gave it to her: "It's a good read," I said. "If you want to know about Judaism, this is a great book to start with."

She read it, and asked for another book. And then another. And -- well, long story short, my friend decided to embark on the serious study of Judaism. Two years later, she became a Jew by choice -- an Orthodox Jewish convert. Ten months later we were married. That was 21 years ago. I wish we had thought of inviting Herman Wouk to our wedding. Alas, it's too late for that now.

Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author