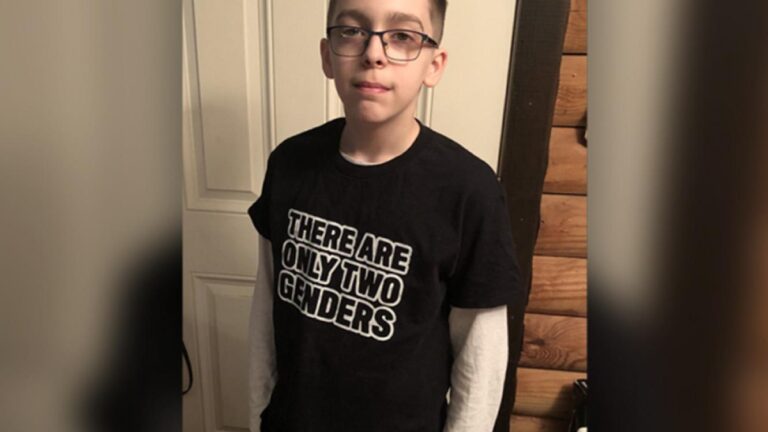

When Liam Morrison, a seventh-grader in Middleborough, showed up at Nichols Middle School last March wearing a T-shirt bearing the message "There Are Only Two Genders," he was ordered by the principal to take it off. He politely refused, so the principal suspended him from class for the rest of the day. He subsequently came to school wearing the T-shirt with the word "Censored" taped over the original message, so that it read: "There Are [Censored] Genders." The principal, impervious to irony, told him that was banned too. He was allowed to return to class only after putting on a different shirt.

Morrison knew, of course, that the message on his shirt contradicted a view promoted at Nichols Middle School, where students are encouraged in June to "wear your Pride gear to celebrate Pride Month" and there is an active Gay-Straight Alliance club. What he may not have known is that by wearing something to express a view frowned on at his school, he was exercising a right for which another middle school student waged a famous fight half a century ago.

In a landmark decision in 1969, the Supreme Court upheld the right of Mary Beth Tinker, a 13-year-old junior high student in Des Moines, to wear a black armband to class in protest against the Vietnam War. Tinker and some other students decided to wear such armbands after attending an antiwar rally. When school officials learned of their plans, they adopted a policy banning students from wearing armbands on pain of suspension. Tinker and the others defied the policy and were barred from class. With help from the Iowa Civil Liberties Union, the students filed a lawsuit, claiming that the school district had violated their First Amendment right to peacefully express their views.

The trial and appellate courts backed the school board. But when the case reached the Supreme Court the justices ruled decisively the other way. Neither students nor teachers "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate," wrote Justice Abe Fortas for the majority in Tinker v. Des Moines. The students who donned armbands had been wrongly punished "for a silent, passive expression of opinion, unaccompanied by any disorder or disturbance on [their] part," the court held. The students had not interfered with school routine. They had not endangered "the rights of other students to be secure and to be let alone." They had merely expressed a view not everyone shared.

The justices emphasized that the Des Moines schools had not disciplined students who wore other "symbols of political or controversial significance." By prohibiting only an antiwar symbol, the schools plainly intended to suppress a particular viewpoint. That, the high court declared, "is not constitutionally permissible."

Now it's Morrison's free speech that is at stake. As in Des Moines, the school prevailed at the district court level. Federal Judge Indira Talwani ruled in June that Middleborough officials were permitted to silence Morrison's speech on the grounds that students who identify as transgender "have a right to attend school without being confronted by messages attacking their identities."

But Morrison attacked no one, nor implied that anyone should be attacked. His first T-shirt merely conveyed his general view that gender is binary. His second T-shirt didn't even do that — it noted only that his view on the subject had been censored.

Now Morrison has turned to the US Court of Appeals for the First Circuit in Boston. His plea is like that of Mary Beth Tinker in the 1960s: Under the Constitution, even a middle school student may peacefully express an opinion. He is asking the judges to reaffirm the principle that government officers may not stifle certain ideas merely because some people find them offensive.

In court filings, Middleborough's lawyers argue that the school was entitled to suppress Morrison's message out of concern that it could have led to "disruption." Yet contrary messages are permitted. No discipline was imposed when a student came to class in a "He she they, it's all okay" T-shirt. School administrators cannot have it both ways, allowing students to express the popular side of a debatable issue but silencing those who disagree because their opinion might provoke an angry reaction. The First Amendment does not bow to the heckler's veto. The expression of a disfavored opinion "may start an argument or cause a disturbance," the Supreme Court observed in Tinker, "but our Constitution says we must take this risk."

The bottom line is clear. Liam Morrison's school doesn't have to agree with his opinion. But it cannot punish him for expressing it.

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe, from which this is reprinted with permission."

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author