The days when a US president could expect to attract upward of 40 million, 50 million, or even 60 million pairs of eyeballs to his annual keynote address on Capitol Hill are over. Donald Trump managed to lure 47 million viewers when he delivered his 2019 address, but that dropped to 37 million in 2020. Biden's first two State of the Union appearances averaged an audience of 32.5 million.

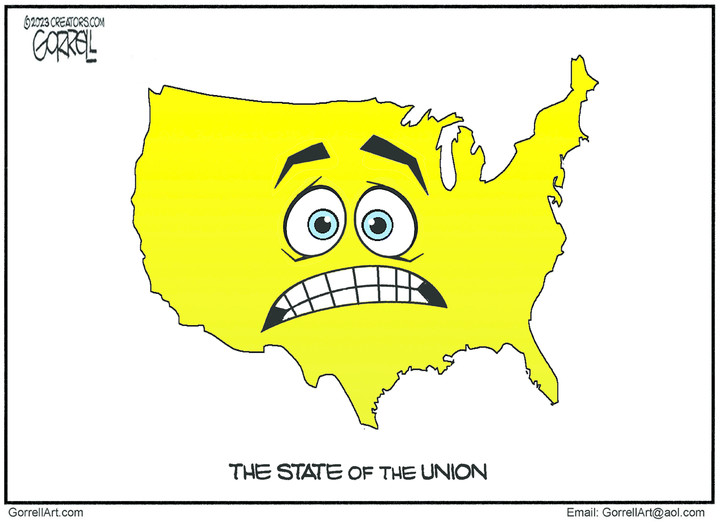

By contrast, when Super Bowl LVII airs Sunday, it's likely to be watched by a TV audience of 110 million or more. Americans know what they like and, for most of them, the State of the Union address — in which the president pats himself on the back, recites a long list of policy proposals unlikely to go anywhere, extols a few notable guests in the gallery, and is repeatedly interrupted by applause or ovations from members of his own party — ain't it. New to Arguable? Click here to subscribe.

What should be done about a State of the Union address in which fewer and fewer Americans have any interest? My advice is to emulate the Coca-Cola Company's strategy for dealing with the widespread rejection of New Coke: Give it up as a lost cause and return to the classic product that worked so well for generations.

But Josh Tyrangiel, a creator of "Vice News Tonight" for HBO, has a different idea. He thinks the State of the Union address just needs to be punched up with a little hoopla and razzmatazz.

"It's way past time to integrate other media" into the president's speech, Tyrangiel wrote in a recent guest column for The New York Times. He suggests transforming the State of the Union into a high-tech theatrical production, complete with dimming the lights in the House chamber, airing short films, bringing in the secretary of state by video hookup from Kiev, and displaying graphics that will make the White House's data "dance." The president should refashion his appearance before Congress into a "meticulous storytelling machine," Tyrangiel declares. "Dare to cross the nerd Rubicon," he advises Biden.

Yeah, I don't think so.

The imperious Woodrow Wilson revived a practice rejected by every president since Jefferson: an address to a joint session of Congress. The core problem with the State of the Union speech is that it's a speech. Not just a speech, but a quasi-royalist oratorical spectacle that symbolically obliterates the constitutional division of federal power among three coequal branches. The annual event — with the president, alone on the podium, being attended to by lawmakers, diplomats, uniformed military officers, and even Supreme Court justices in their black robes — smacks disturbingly of the British monarch's "Speech from the Throne."

None of this is appropriate for a government of the people, by the people, and for the people. Presidents are obliged by Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution to provide Congress from "time to time" with information on the "state of the union" and to "recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient." But nothing in the Constitution requires the chief executive to do so by speech. The first two presidents, George Washington and John Adams, did appear before Congress in person. But Thomas Jefferson, who abhorred what he called the "pompous cavalcade" to Capitol Hill, put an end to that practice. Very early in his presidency he let it be known that his first annual message to Congress, "like all subsequent ones," would be in writing.

The change was widely applauded by Jefferson's allies. US Senator Michael Leib of Pennsylvania rejoiced to see an end to "all the pomp and pageantry, which once dishonored our republican institutions. . . . Instead of an address to both houses of Congress made by a president who was drawn to the Capitol by six horses, and followed by the creatures of his nostrils, and gaped at by a wondering multitude," Leib wrote with satisfaction, "we had a message delivered by his private secretary, containing everything necessary for a great and good man to say."

Jefferson's innovation became the standard. For 112 years, every American president — Democrats, Republicans, and Whigs alike — fulfilled his constitutional obligation by dispatching an annual written report to Congress. Not only did presidents not trek to Capitol Hill, it came to be firmly understood that presidents must not intrude on congressional turf.

Then came an unfortunate development: Woodrow Wilson was elected to the White House.

The 28th president, imperious and arrogant ("Princeton's answer to Benito Mussolini," Kevin D. Williamson once called him), made no secret of his disdain for the separation of powers ordained by the Founders. With a commitment to democratic norms that was shaky at best, he maintained that the president alone represented the people. So it was not out of character when Wilson decided to disregard the understanding that Congress was off-limits to the occupant of the White House. Not since 1801 had a president gone up to Capitol Hill to harangue Congress on what he expected of them and when Wilson announced that he meant to do so, reported The Washington Post in 1913, "all official Washington was agape."

Wilson's precedent didn't take hold at once. His immediate successor, Warren G. Harding, followed Wilson's lead and delivered State of the Union speeches, but his successor, Calvin Coolidge, reverted to the time-honored practice of sending an annual message in writing. So did Herbert Hoover. Only when Franklin D. Roosevelt came along was Wilson's practice revived. The advent of television then cemented it in place. Now every president, Republican and Democrat alike, engages in this annual ritual of political self-aggrandizement. And most Americans tune it out.

Jefferson was right. An American "speech from the throne" is a sacrilege, suitable for a Caesar, a Duce, or a Sun King, perhaps, but not for the president of a democratic republic. The imperial presidency doesn't need more bells, whistles, electronic whiz-bangery. It needs more modesty and humility.

Canceling the State of the Union address would be a fine step in the right direction.

Jeff Jacoby is a columnist for The Boston Globe, from which this is reprinted with permission."

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author