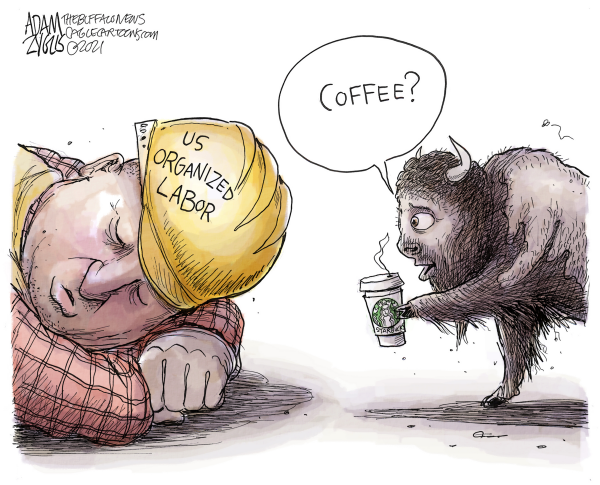

"US Labor Unions Are Having a Moment," cheered Time magazine, which observed that "after decades of erosion in both influence and power," unions were experiencing "their best chance in recent memory to claw back lost ground." Since August of 2021, strikes had been declared at dozens of workplaces, as unions seemed to gain strength from the tight labor market and the presence of a new Democratic administration in Washington.

The New Republic exulted too. "America Is in the Midst of a Dramatic Labor Resurgence," it rejoiced in October. Around the country, wrote Faiz Shakir, workers were "standing up for basic dignity and respect on the job in a historic way."

They are striking; they are picketing; they are demanding fair contracts. They are forming new unions on campuses and coffeehouses, and they are walking out on low-wage jobs at Burger King, Dollar General, and elsewhere. In short, laborers are demanding their due. And it is infectiously spreading from workplace to workplace.

Similar stories appeared on NPR ("The pandemic could be leading to a golden age for unions"), the California news site Cal Matters ("Here's why labor unions are winning again"), and in Fortune (" Could Gen Z bring unions back into the mainstream?") And if more evidence was needed that Big Labor was on the upswing, much was made of a new Gallup poll showing that Americans' approval of labor unions had climbed to 68 percent, the highest level since 1965.

Joe Biden was heavily backed by Big Labor in the 2020 election, but unions so far haven't seen much return on their investment in his candidacy. The tide is flowing in the other direction. Americans may voice their approval of labor unions in opinion polls. But fewer and fewer of them actually want to be in unions. Tens of thousands of workers pitched their union cards last year, even as Big Labor and its cheerleaders were celebrating a supposed "dramatic labor resurgence." Perhaps unions ought to spend less time reveling in their own propaganda, and more time trying to understand why American workers — no matter what they say to Gallup and Pew — are just not that into them anymore.

But while such articles enthusiastically pointed out the trees, they entirely missed the forest: Union membership fell by a quarter of a million members last year, extending a trend of declining union enrollment that has now lasted nearly 40 years. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that at year's end, just 14 million American workers belonged to unions and the union membership rate (the unionized share of the workforce) was only 10.3 percent. In 1983, when the BLS began compiling such data, the union membership rate was 20.1 percent — nearly double the current figure — and there were 17.7 million union workers. Over the past four decades, the number of workers in the US economy has grown by 50 million, yet the number of union members has dropped by 3 million.

It is true that a majority of Americans approve of labor unions — in the abstract. In a Pew survey last summer , 55 percent of respondents said that unions have a positive effect on the way things are going in the country and 60 percent described the long-term decline in the share of workers represented by unions as bad for working people. But what Americans say to pollsters is contradicted by their own life choices. US employees may think well of unions in theory, but in practice they aren't flocking to unionized workplaces. When Americans move from one state to another, they are much more likely to relocate to a right-to-work state — i.e., a state where no one can be forced to pay union dues as a condition of holding a job. States like Massachusetts, where compulsory unionism is lawful, have been on the losing end of domestic migration for years.

In short, public approval of unions bears little relationship to membership in unions. In the Pew survey, young workers expressed the greatest level of support for unions, yet that's the age cohort with the lowest union membership rate. Conversely, while older workers are more likely to belong to unions, they are much less likely to describe them as having a positive effect on American life. That dichotomy certainly resonates with me. I work in a union shop and have therefore been paying union dues for decades. But I am no fan of the influence unions have had on US politics and policymaking.

Especially in the public sector.

Only about 1 in 16 workers in the private economy belong to unions. But among public-sector employees, a whopping 33.9 percent are unionized — more than 1 in 3. The spread of unions within government agencies has been a deeply unhealthy development. Today, Big Labor's clout in the public sector might seem to be part of the natural order of things. But there was a time when even pro-labor Democrats like Franklin D. Roosevelt considered it obvious that collective bargaining was incompatible with public employment.

"The process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service," FDR wrote in 1937 to the head of the National Federation of Federal Employees. In the private sector, organized employees and the employer meet across the bargaining table as (theoretical) equals. But in the public sector, said Roosevelt, "the employer is the whole people, who speak by means of laws enacted by their representatives in Congress." Allowing public-employee unions to engage in collective bargaining, he knew, would open the door to the manipulation of government policy by a privileged private interest.

That was exactly what happened once unions were allowed to organize public-sector workplaces. To many people, the argument that government employees should have the same right to bargain collectively as workers in the private sector seemed reasonable. But it wasn't reasonable at all. Labor negotiations in government are emphatically not like those in the market economy.

In private workplaces, unions contend with management for a share of the profits that labor helps create. But in the public sector, there are no profits to share. There are only taxpayers' dollars, which neither government employees nor government managers produce. As for the taxpayers who do create those dollars, they are denied a seat at the table when public unions negotiate over wages and benefits.

Instead, government sits on both sides, negotiating with itself over how to spend the people's money.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author