On Tuesday evening, amid much splendor and spectacle, the president of the United States will be welcomed by a joint session of Congress, there to be cheered and applauded like a homecoming conqueror, and, before an audience of lawmakers, diplomats, military officers, and dignitaries, to deliver his State of the Union oration in a live nationwide broadcast.

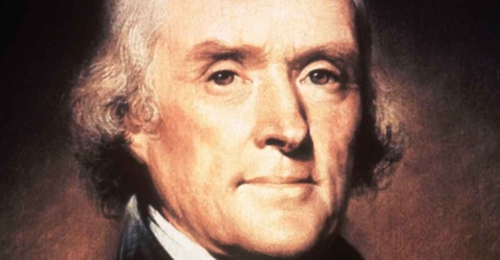

It is the most preposterous and gaudy ritual in American political life. Thomas Jefferson will be turning in his grave.

Like Moses, Jefferson was burdened with a speech impediment and disliked public speaking. Unlike the Hebrew lawgiver, Jefferson wasn't compelled by Heaven to preach to the multitudes. And, as he knew perfectly well, he wasn't compelled to do so by the Constitution, either.

Article II, Section 3 of the Constitution obliges the president to periodically "give to the Congress information of the State of the Union" and to "recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient." George Washington and John Adams elected to do so in person, though nothing in the constitutional language requires a speech. But Jefferson detested the "pompous cavalcade" to Capitol Hill, which in his view smacked disturbingly of the British monarch's annual "Speech from the Throne." Very early in his presidency, therefore, he let it be known that his first annual message to Congress, "like all subsequent ones," would be in writing.

He was as good as his word, and the change was widely applauded.

"All the pomp and pageantry, which once dishonored our republican institutions, are buried in the tomb of the Capulets," wrote one admiring Pennsylvania congressman. "Instead of an address to both houses of Congress made by a president who was drawn to the Capitol by six horses, and followed by the creatures of his nostrils, and gaped at by a wondering multitude, we had a message delivered by his private secretary, containing every thing necessary for a great and good man to say."

Jefferson's innovation became the unvarying norm. For the next 112 years, every American president — Democrats, Republicans, and Whigs alike — fulfilled the constitutional mandate by sending written reports to Congress.

And then, alas, came Woodrow Wilson.

Imperious and antirepublican, Wilson had long criticized the separation of powers established by the Constitution. Only the president could truly represent the will of the people, he believed, and it was therefore appropriate that he appear before Congress in person to let legislators know what he expected of them. For more than a century, presidents of every stripe had accepted and honored the principle that the executive, legislative, and judicial branches were separate and co-equal. Presidents didn't intrude on lawmakers' turf, let alone presume to lecture them on his political wish-list. Wilson's reversion to pre-Jeffersonian practice was jolting.

"All official Washington was agape last night over the decision of the president to go back to the long-abandoned custom," reported The Washington Post on April 7, 1913. Considering some of Wilson's other achievements — he segregated Washington, D.C., opposed female suffrage, approved a law to sterilize the disabled, screened the racist "Birth of Nation" in the White House, championed a federal income tax, and endorsed a ruthless civil-liberties crackdown — it would be stretch to describe Wilson's revival of the in-person State of the Union address as his worst offense. But it's on the list.

Members of Congress jostle for center-aisle seats — sometimes staking them out hours in advance — in hopes of scoring a public handshake as the president arrives in the House chamber for the State of the Union address. |

As president, Calvin Coolidge reversed Wilson's grandiose precedent, but it was revived again by Franklin Roosevelt and has been the norm ever since. The advent of television has turned the yearly pageant into a regal political infomercial. It now includes staged shout-outs to specially-invited citizens in the House gallery, members of Congress jostling for center-aisle seats in hopes of scoring a presidential handshake, and the wholly inappropriate presence of robed Supreme Court justices and the Joint Chiefs of Staff in uniform. News organizations count the number of standing ovations each president receives. And woe betide anyone in the audience who so much as murmurs disapproval of the executive during his hour of exaltation.

It isn't a healthy practice. What the Constitution's framers intended as a matter-of-fact directive — that presidents supply lawmakers with useful information and policy proposals — has become an antidemocratic extravaganza that would have horrified Jefferson. The State of the Union broadcast fuels the cult of the presidency. It encourages the delusion that the nation's "state" can somehow be embodied by a single individual, a Great Leader capable of crafting a sweeping political agenda that will bring the millennium.

The lone saving grace of the modern State of the Union Address is its reputation for tedium. Last year, fewer than 32 million viewers tuned in to the speech, a decline of more than 20 million since President Obama's first State of the Union in 2009, and the lowest ratings since Bill Clinton's final address in 2000. To political junkies, the "pompous cavalcade" may be irresistible. To the vast majority of Americans, it's just a bore.

Comment by clicking here.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author