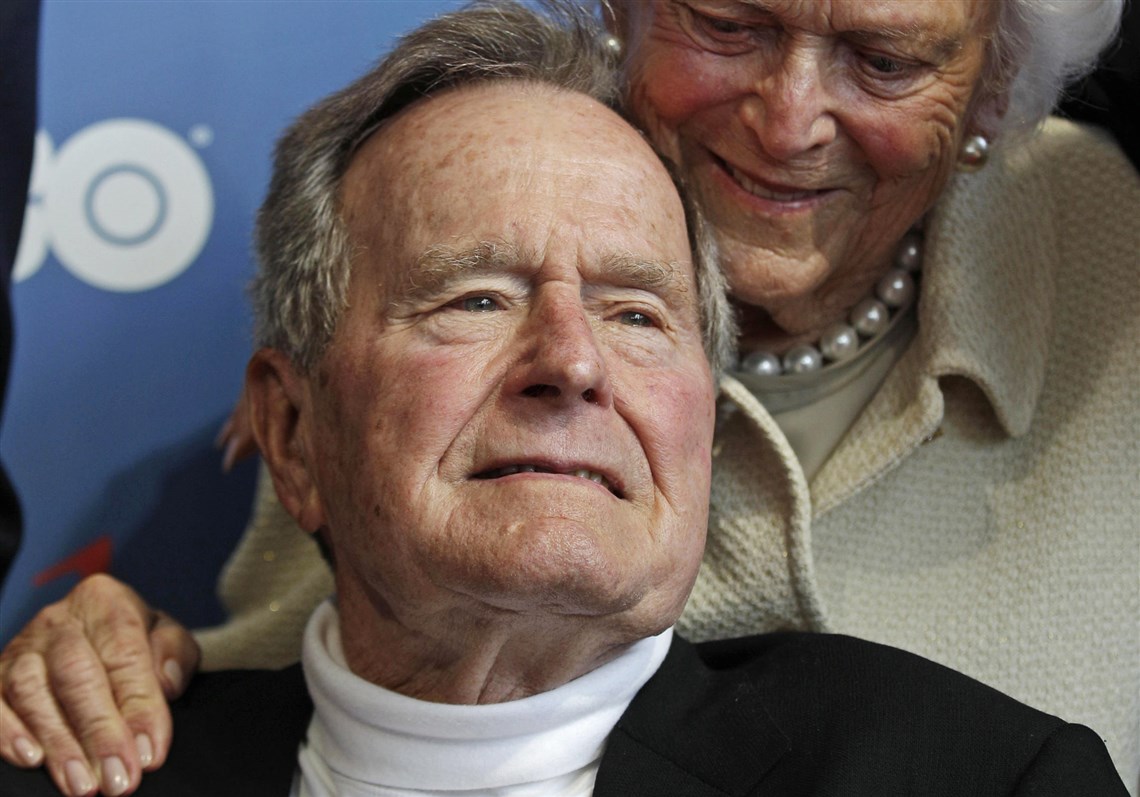

George H.W. Bush is a 93-year-old with a formidable bucket list. He's in a wheelchair, and his wife, Barbara, uses a walker and a motorized scooter. The other day, Jean Becker, his chief of staff, told him the high-speed rail project in Texas might not be completed until he is 99. "I'm in," he told her.

Nearly four decades ago, Mr. Bush, energy and urgency personified, campaigned for president by asserting that he was "up for the '80s." The 41st president, now America's most beloved senior citizen and most respected senior statesman, is still upbeat. Ask him a question and he says, "Sure." Ask another and he answers, "Yes!" Follow up with a third and he asks, "Why not?"

He's back here in Maine, in the grand compound once known as the Summer White House, which is still a tourist destination attracting dozens of visitors to a wayside viewing area a quarter-mile away. The surf crashes against the concrete wall, the mallards gather on the grassy slope.

For most of his life, he has come here in summertime, walking the rocky beach at the base of the point, cruising the inlets in a cigarette boat that still takes him a few times each summer south to the beach town of Ogunquit, there to have a shore dinner overlooking tranquil Perkins Cove.

There are five pictures of him scattered around the wood-paneled walls of Barnacle Billy's restaurant. Diners pause from their lobsters and steamed clams to inquire about "the president." No one asks which president they mean.

"President Bush is a bit like a mountain," said Jon Meacham, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author who recently wrote a biography of Mr. Bush. "You can best understand his formidable dimensions from a suitable distance." Mr. Meacham was here last week to deliver a homily - the topic, "Faith and Doubt," hauntingly appropriate for the times - at St. Ann's, the Episcopal summer church constructed of sea-washed stones and hard pine hammer-beam trusses where Mr. Bush's parents were married.

The sun rises on America here. During Mr. Bush's presidency, from 1989 to 1993, the gray clapboard house on Walker's Point, with its breathtaking ocean views, was an unrivaled seaside power center. John Major of Great Britain, Brian Mulroney of Canada, Yitzhak Rabin of Israel, Lech Walesa of Poland and King Hussein of Jordan - all figures now of history, some only dimly remembered - were feted here, felt the bracing breezes here, smelled the salt air here.

Years later, when his son, George W. Bush, was president, Vladimir Putin of Russia walked the promontory that juts into the icy Atlantic here. Later, the three presidents went fishing.

The elder president, then a mere 83, pushed the boat, a little perilously, to top speed. Until recently, it was the only speed he knew. (There apparently were no speed limits for golf carts during his presidential years at Cape Arundel Golf Club, when Mr. Bush pioneered a new sport that he called speed-golf.)

Now the speed is gone from Mr. Bush, and now his guests tend to be family members. The other day, the clouds low and the Maine sky a frosty, forbidding gray, Mr. Bush, wearing a royal blue sweater and expertly pressed khakis, was in his office. Outside, his daughter, Doro, pulled up in a car with a load of supplies. Former Gov. Jeb Bush of Florida, in plaid shorts and a light gray T-shirt, strolled by. "He's slowed down, but he's still got his game, and he's still telling jokes," the younger Mr. Bush said. Then he added: "Both my mom and dad are special people."

That is a son's tribute to his parents, a sentiment, to be sure, repeated countless times by children in their 60s about parents in their 90s. But Mr. and Mrs. Bush hold a special place in American life today, when the red-hot issues of the late 1980s and early 1990s have faded to sepia brown, when the passions of the time seem tame compared to those that spill across cable television now and when the country seems to yearn for the civility of the Bush years, today remembered fondly, even nostalgically. One of the top movies of Mr. Bush's last year in office was "The Last of the Mohicans." Make of that as you wish, but perhaps that label belongs to Mr. Bush himself.

Mr. Bush is the last of a breed, the sort that celebrates breeding - a discomfiting notion, perhaps, in a democratic nation - but that also prizes public service and makes way, in time and with grace and generosity, for the new and for the unfamiliar, sometimes even the uncomfortable. That, above all, was Mr. Bush's ideology. "He is the personification of a great citizen," said Andrew H. Card, transportation secretary under the first President Bush and White House chief of staff under the second.

Mr. Bush - a "servant leader," in the words of Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio - was a conservative, but primarily what he conserved were the old values, modesty and manners. He did not fit Theodore Roosevelt's prescription of a president who had to know "how to play the popular hero and shoot a bear."

But he could fight fiercely; former Gov. Michael S. Dukakis, whom he defeated in 1988, could testify to that, and so could former Rep. Newt Gingrich, who mercilessly pilloried the president for compromising with the Democrats on taxes in 1990. Mr. Bush - a master of statecraft if not always of speechcraft - hewed to the notion, and the hope, expressed in his Inaugural Address, that "this is the age of the offered hand." That is all the more appealing today, in the age of the clenched fist.

"His health is not good, and for the most part he is disabled," said Marlin Fitzwater, Mr. Bush's former press secretary, who visited recently. "Yet just being around him and knowing what he stands for is inspirational." And ironic, for here in coastal Maine, where the sun first hits American soil, its oldest president is in his sunset years.

David Shribman, a Pulitzer Prize winner in journalism, is executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author