Arguably, galloping inflation did more than anything else to unravel Jimmy Carter's presidency. He proved powerless to address the issue that, as political journalist Theodore White wrote, was unrivaled "as a pressure on the American mind, its mood and family planning for the future."

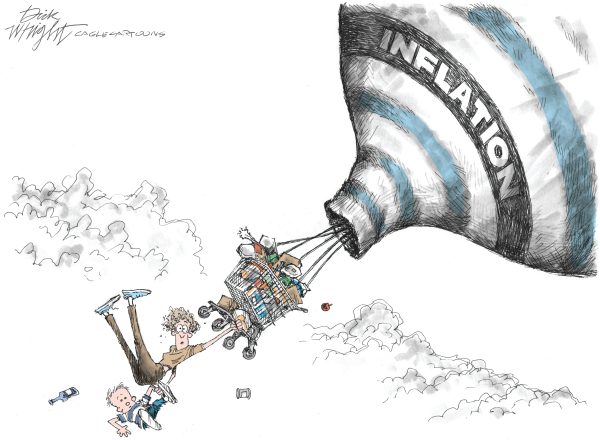

Now, we aren't anywhere close to the late 1970s, when inflation had been running high for years and hit double-digits. But the latest numbers — with prices increasing 6.2 percent year over the year, marking the biggest annual increase in more than 30 years — should be a fire-bell in the night for Democrats.

There have been two crises President Joe Biden created or exacerbated, at the southern border and in Afghanistan, and these latest price numbers point to the possibility of a third and even more consequential one.

Economic discontent destroys presidencies and brings governing political parties low. Biden's rating on the economy has already been taking a beating (57 percent disapproved of his handling of the economy in the latest NBC News poll), while majorities of Democrats, Republicans and independents agree that "inflation is a very big concern to me."

Large-scale forces beyond Biden's power to fix are at play in the rising prices. His policy program has tended to make the problem worse rather than better, though, and the buck (and its eroding purchasing power) is going to stop with him regardless.

For the longest time, the Biden White House's response to inflation concerns has been to pooh-pooh them, and attack the messenger. As POLITICO Playbook recently pointed out,, the White House scoffed at economist Larry Summers when he warned earlier this year that fiscal stimulus on a World War II-scale might cause unintended effects, including the chance it would "set off inflationary pressures of a kind we have not seen in a generation."

Contra Summers, White House economic adviser Jared Bernstein predicted in April that inflation would rise modestly for several months before fading back to a lower level. Well, here we are, getting close to the end of the year, with inflation indeed at its highest level in a generation.

Game, set, match Larry Summers.

Conservatives cried wolf about inflation when the Federal Reserve adopted its program of quantitative easing during the financial crisis, so it's understandable progressives would be dismissive of new cries this time around. But sometimes the wolf is at the door, or at least in the neighborhood.

Bernstein characterized the rising prices as "transitory," a word that has been used so frequently by inflation-doubters that it's become parodic. John Maynard Keynes famously said in the long run we are all dead, so in a similar spirit, it might be that everything is transitory. Or it could be said that inflation is proving "enduringly transitory," or "stubbornly transitory."

Rising prices are being driven by a global mismatch between demand and supply as the economy recovers from the pandemic while disruptions in production persist. At the same time, bottlenecks are disrupting every point along the U.S. supply chain. Other countries in the world are expediting rising prices, yet inflation in the U.S. has been worse than elsewhere, and Biden's agenda clearly wasn't designed with an inflationary environment in mind.

With gas and fuel oil prices up 50 percent and more over the past year, maybe it isn't such a good time to be pursuing a full-court press against fossil-fuel producers in an economy that will rely, like it or not, on fossil fuels for a very long time.

Nonetheless, the Biden administration has been openly hostile to the oil and gas industry as part of its climate agenda, including canceling the Keystone XL pipeline, blocking oil and gas leases, and seeking, overall, to disfavor oil and gas toward the goal of making it obsolete. Biden is now in the bizarre position of urging OPEC to produce more oil to reduce prices when, at the end of the day, the White House doesn't want the U.S. sector to do the same.

With the country already awash in new federal dollars from the multiple spending bills that have gone out the door over the past 18 months, perhaps it isn't a great idea to layer the Democrats' massive social spending bill on top. Certainly, the intuitive response to higher inflation isn't to push for yet higher federal spending, a point Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) has repeatedly made.

With labor shortages and supply disruptions plaguing the economy, it might be that continuing to stoke demand with various payments and subsidies — while discouraging supply, either by making it easier for people to stay out of the work force or by raising taxes and tightening regulations — isn't such a grand idea.

Broadly speaking, the progressive program is always essentially inflationary, since it involves constraining supply through various government strictures and then subsidizing demand — a dynamic that can be seen in the housing, college and health care sectors.

Showing he hasn't lost his instinct for basic political self-preservation, Biden recently has noted the deleterious effects of inflation and vowed to fight it as a top priority. He also has, not very convincingly, redefined his infrastructure and Build Back Better proposals as anti-inflationary, though no one ever mentioned this when the bills were being conceived or sold over the past year.

But Biden's BBB plan is now evidently to be considered the equivalent of Gerald Ford's WIN — the Whip Inflation Now program that didn't whip the inflation of the 1970s, now or ever.

Since he's not going to reverse field on any of his major priorities, Biden's best bet is that his jawboning and pushing at the ports and other points along the supply chain can make a difference at the margins, while companies figure out ways to untangle the mess over time. In the meantime, the global energy crunch could resolve itself as supply catches up to demand. That would presumably take the edge off inflation next year, even if there's room for housing prices, for instance, to keep rising.

What is not going to work, and hasn't worked, is trying to talk people out of the lived reality of higher prices.

The labor market has been tight, but it avails workers nothing if wages don't keep up with inflation. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, real average hourly earnings fell 1.2 percent from October 2020 to October 2021, and dropped 0.5 percent from September to October of this year.

Whether prices continue to outstrip wages might be the best metric for the scale of Democratic congressional losses next year and the ultimate fate of Biden's presidency.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author