There's been a lot of excitement about last week's ruling by a federal judge in

But even though I'm in sympathy with the outcome, I find the celebrated opinion itself oddly unpersuasive, perhaps because the judge sets out to answer the wrong question. Appalled as I am by the administration's assault on dissent, I wonder whether constitutional rights give us the proper lens through which to study what's gone so constitutionally wrong.

Here's a nice, clear democratic principle: The government should not keep track of what the people subject to its jurisdiction are saying — no surveillance, no recordkeeping, and certainly, no punishment. Yes, there are rare exceptions, but they must remain rare. Otherwise, debate suffers, which means that democracy suffers. Here's a corollary: The government should neither be granted nor presumed to possess broad powers that would enable it to violate the principle.

As any libertarian will be quick to note, that's not really a point about the rights of individuals; it's a point about the structure and limits of government.

To see why, let's turn to

The deportations around which the case revolves arise from the exercise of the secretary of state's statutory authority to deport visa holders for otherwise lawful "beliefs, statements, or associations," but only if failing to do so would, in the secretary's judgment, "compromise a compelling

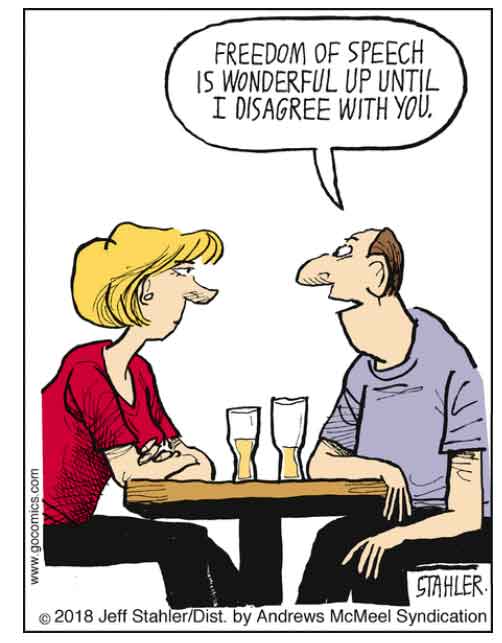

These are breathtaking grants of authority about which, as scholars often complain, there's remarkably little law. The issue before the court — an issue around which judges have traditionally tiptoed — was whether the First Amendment limits those and similar discretionary federal powers over visa holders. For example, the government cannot punish one of its own citizens for the most vile expression of anti-Semitic views; contrary to what left and right too often seem to think, the First Amendment admits no exception for "hate" speech. But what about a noncitizen on a student visa? Are the rules the same? That was, until recently, ground largely untrod.

I'm a near-absolutist on free speech, so I like the outcome. But the opinion itself is problematic — sufficiently problematic, I suspect, to invite reversal on appeal. For one thing, it's unnecessarily long (more than 160 pages) and, to be frank, sloppily written — with lots of repetition, meandering detours into politics, and such elementary errors as confusing "staunch" and "stanch." The

The difficulties emerge, I suspect, not from any inability to cope with the issues, but from the challenge of trying to fit into a First Amendment framework what's really a problem of government power in a democracy.

Another immigration-related example might help make the point. First Amendment fans are up in arms about Apple's recent decision to yield to

But the issue isn't whether true information can be misused by those with wicked agendas; the issue is the lack of debate over what amounts in practice to government pressure for a ban. The ease with which the

The real challenge we face is the vast power we have concentrated in the federal government in general and in the presidency in particular. As much as we might talk about courts as checks on executive authority, the sad truth is that

Maybe it's too late to imagine a smaller federal establishment with fewer powers. But as current events illustrate, if that's the case, then the only real check is the ethical compass of the occupant of the

____

(1) In addition, the opinion seems to misread the Supreme Court's most recent cases on the standing of associations to assert the rights of their members — a simple ground for reversal, should an appellate court prefer not to reach the merits of the case.

Stephen Lisle Carter is an American legal scholar who serves as the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Law at Yale Law School. He writes on legal and social issues.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author