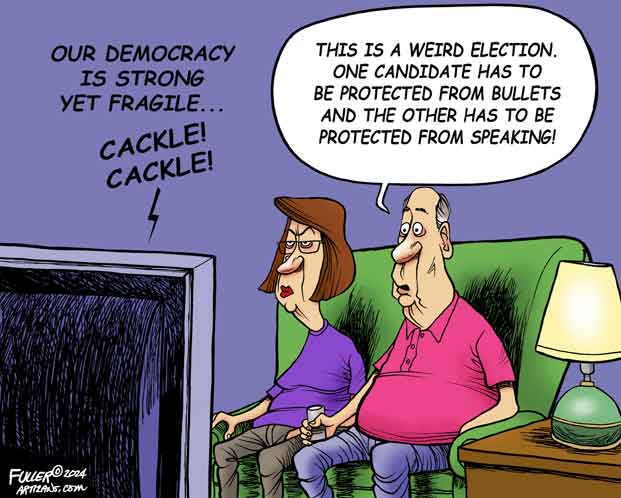

As the presidential campaign reaches peak intensity, we are seeing an interesting phenomenon: journalists who don't want to know some very basic information about one of the candidates.

That candidate, of course, is Vice President Kamala Harris, who has been famously sketchy about what she would do in a number of key policy areas, such as the economy, immigration, foreign policy, and much more, if she were to win the White House. All Republicans, and even some Democrats, want Harris to be more forthcoming about her plans, especially since she was quite open about her positions when she first ran for president, in the 2020 Democratic primaries. In addition, all journalists want Harris to be more open, on the simple principle that more information is better.

Actually, not all journalists. What has emerged recently is a new type of journalist who wants less, rather than more, information about the most important story of the moment. A few recent examples.

New York Times columnist Bret Stephens recently wrote a piece headlined, "What Harris Must Do to Win Over Skeptics (Like Me)." Stephens went through a number of policy questions, including Iran, Ukraine, Hamas, federal spending, climate, housing, nuclear power, and more, about which Harris has not given full descriptions of her positions — or any descriptions at all. "All this helps explain my unease with the thought of voting for Harris — an unease I never felt, despite policy differences, when Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden were on the ballot against Trump," Stephens wrote. "If Harris can answer the questions I posed above, she should be quick to do so, if only to dispel a widespread perception of unseriousness. If she can't, then what was she doing over nearly eight years as a senator and vice president?"

Later, Stephens appeared on HBO's Real Time With Bill Maher with the MSNBC anchor Stephanie Ruhle. First, Stephens had to establish his anti-Trump bona fides. He would never be taken seriously by the audience unless he did that. "I'm never going to vote for Trump," Stephens said, "but I'm not sure I want to vote for Kamala. And my fear is that she doesn't really have a very good command of what she wants to do as president." Stephens suggested that "it would be great" if Harris would sit down with Ruhle or other journalists and answer questions.

One might think Ruhle would want that, too. But she does not. She was, in fact, appalled at Stephens's idea. "Let's say you don't like her answer. Are you going to vote for Donald Trump?" Ruhle asked Stephens. No, said Stephens, and no one else should, either. "Kamala Harris is not running for perfect," Ruhle responded. "We have two choices. And so there are some things you might not know her answer to, and in 2024, unlike 2016, for a lot of the American people, we know exactly what Trump will do, who he is, and the kind of threat he is to democracy."

Stephens pointed out that it's not just a few things we don't know about Harris. It's much more than that. "People also are expected to have some idea of what the program is that you're supposed to vote for," he said. "I don't think it's too much to ask for her to sit down for a real interview." Ruhle replied: "I would just say to that, when you move to nirvana, give me your real estate broker's number, and I'll be your next-door neighbor. We don't live there."

It was a remarkable moment. As Ruhle, the journalist, saw it, wanting a campaign in which the leading candidate for president of the United States submits to scrutiny about her policy positions is an unreachable state of perfection. Voters simply don't need to learn anything more about Harris.

Here's the interesting thing. After video of the exchange began to circulate, other journalists agreed with Ruhle. "This is infuriatingly disingenuous," wrote the Atlantic's Tom Nichols about Stephens's suggestion. "'We don't know her positions' is a straw man and Stephens knows it. I'm pretty sure I know what her administration will look like. … 'Undecideds' who say 'but I want to hear more about her policies' are not undecided. They want Harris to walk into an unwinnable policy debate with the media while Trump rants like a madman, so they can rationalize not voting for her."

Other journalists chimed in. "Exactly," said the Atlantic's Anne Applebaum. "Real moral clarity from Stephanie Ruhle," said Vanity Fair's Molly Jong-Fast. "This is perfect from my friend Stephanie Ruhle," said MSNBC's Nicolle Wallace.

Look at another example. During the Sept. 10 debate with Trump, Harris stirred a lot of curiosity when she revealed she is a gun owner. Many observers didn't know that and wanted to learn more. What kind of gun? How long has Harris had it? Does she shoot it? Has she ever used it? Neither Harris nor her staff offered any further details. Then, during her town hall with Oprah Winfrey, when Winfrey said she had not known that Harris owned a gun, Harris replied, "If somebody breaks into my house, they're getting shot, sorry," and then broke into laughter. Harris added, "Probably should not have said that, but my staff will deal with that later."

Then, on Friday, a member of Harris's staff, campaign spokeswoman Adrienne Elrod, appeared on CNN. Anchor Jim Acosta had some basic questions about the gun. "You are on Kamala Harris's staff — can you give us some more information?" Acosta said to Elrod. "I'm just curious from a biographical background, what do we know about this firearm that she owns and when did she get it?"

Elrod confirmed that Harris owns a gun and then said, "I can't really comment more than that" beyond saying that Harris "staunchly supports the Second Amendment."

After that, I posted that Harris "keeps saying she is a gun owner but won't say anything about the gun or gun she owns. Her staff won't, either." The reaction on X was instant and hostile — and from another journalist. "What f***ing business is it of yours?" said the journalist Keith Olbermann. Then, from the longtime journalist and journalism professor Jeff Jarvis came the comment, "So f***ing what?" And then followed the X observers, who added things like "It's none of your damn business" and "Who cares? It's her business."

The point of all this is to shed some light on Harris's continuing refusal to reveal precisely where she stands on a number of issues important to voters. Why should she? She has a group of journalists on her side who actively do not want her to answer more questions, do not want her to be transparent on important issues, do not want her to undergo the scrutiny that until now has been routine for major party candidates. They are willing to defend her decision not to talk aggressively.

When it comes to where Harris stands, they don't want to know. And so far, she's not telling them — or us.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author