He visited Del Rio, Texas, recently and refused to use the offending word about more than 10,000 Haitian migrants huddled under a bridge, living among trash with insufficient food and water in sweltering heat. A mere "challenge."

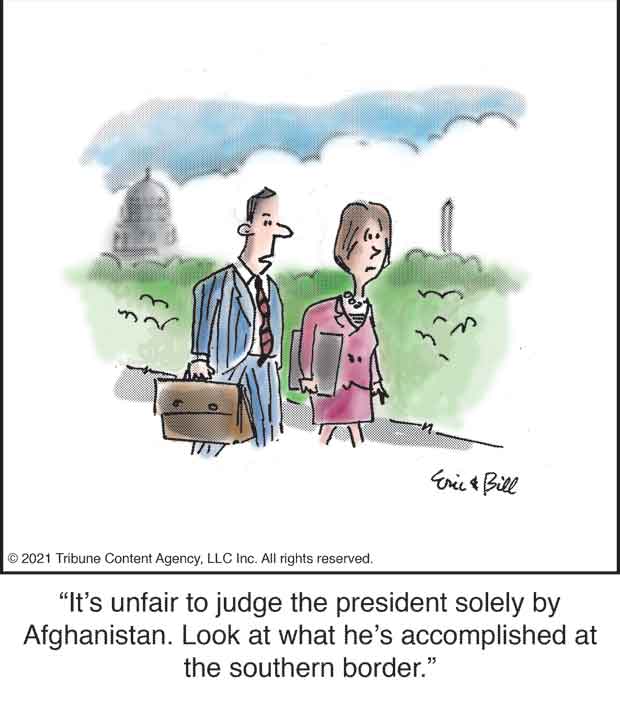

If euphemism and spin constituted competent, Team Biden wouldn’t be coping with a historic surge of illegal crossings at the border that reached another level with the nearly instantaneous creation of an enormous migrant camp in an isolated Texas town.

The Haitian migrants had been crossing for weeks, before the flow exploded over a matter of days. The camp grew from 4,000 the middle of last week to more than 16,000 by the weekend. The images of desperate Haitians wading across the Rio Grande by the hundreds and thousands without anyone even attempting to stop them will likely become an indelible symbol of Biden’s border policy.

Administration officials constantly say that the border is closed, but in important respects it is open. They blame misinformation spreading among migrants, and it’s true that unfounded rumors abound, but the basic perception that our enforcement has major, easily exploited holes is correct.

They blame circumstances, but it’s not as though terrible conditions — poverty and rank misgovernment — are new in countries to our south.

No, the new factor in the equation is President Biden and his determination to blow up Trump policies that had gotten control of the border. Border apprehensions remained at a 20-year high in August. They only dipped slightly from July and otherwise have been on an upward trajectory all year.

The fashionable explanation for the initial rise in migration was that it was simply "seasonality," the tendency of migrants to come to the border in the spring and then drop off when it get hotter. Biden himself confidently asserted this was the dynamic. "It happens every single, solitary year," he said in March.

But his policies overcame this ingrained pattern, enticing more migrants even during the summer months.

As long as people are convinced that they have a good chance of getting into the United States to stay — which is unquestionably the case with unaccompanied minors and family units — there is a strong incentive to make the trek to the border.

Haitians got the message, too. Prior to the latest influx at Del Rio, almost 30,000 Haitians had been apprehended this fiscal year. The previous two years, the number had been in the low thousands.

The administration granted so-called temporary protected status, a protection from deportation, to Haitians residing in the United States as of May 21 of this year. Then it extended it again to include Haitians residing here since July 29 — sending the message that new arrivals might get the status on a rolling basis.

Haitians also knew family units have been getting through.

The migrants at Del Rio haven’t been coming directly from Haiti, but from South America, largely Chile and Brazil, after tens of thousands fled there in the aftermath of the 2010 Haitian earthquake. Dwindling economic opportunities and immigration restrictions sent many migrants into Mexico, and when Mexican officials began to allow them to travel further north, they descended on Del Rio.

Caught off guard (as usual), the Biden team has begun deporting migrants on flights back to Haiti. This has stanched and even reversed the flow for now, although reports say that family units are staying in America.

Unless and until the Biden team realizes that swift exclusion from the US has to apply to almost everyone, the "challenges" at the border won’t let up.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author