The modern political universe began to take shape from the explosive madness of 1968 --- the riots, revolutions, assassinations and war. Political galaxies, special-interest solar systems, legislative black holes were all forming. We live with them today.

There was the moon landing in late July. We thought it was a step toward infinity but, really, it was a last gasp of World War II. The space race began under leadership from two heroes of that war, presidents Dwight Eisenhower and John Kennedy. Its culmination looked much like another scene from that era: brave young men in crew cuts and uniforms, life and death, flags planted on distant ground.

Not even a month later, there was Woodstock, the music festival that turned into an earthquake. It sprang from a different tap root in America's cultural ground - rebellious, spontaneous, Dionysian. Woodstock featured sexy young stoners in long hair and full nudity. Music and acid. Tents pitched on muddy ground.

Two aspects of one nation: NASA honored discipline, planning and order; Woodstock was the opposite of all that. Both sprang from the corner of the American character that asks, "Why not?" Why not strap three men atop a tower of fire and blast them to another world? Why not invite hundreds of thousands of young people to an unprepared field in the middle of nowhere for a gloriously uneven marathon concert?

Both could have ended in disaster. Instead, they stand out as two great moments in a dark period marked by a misbegotten war, domestic terrorism, political scandal and economic strife.

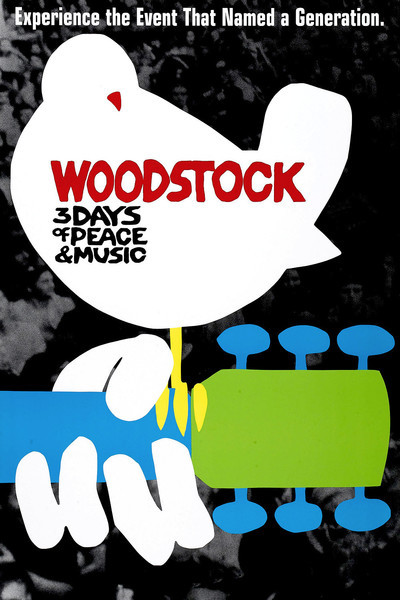

On the 50th anniversary of Woodstock's opening day - today - theaters throughout the country will show an expanded version of the landmark 1970 documentary that preserved the event in all its squalid grandeur.

"Woodstock," the movie, was arguably even more influential than the festival itself, for it brought those "3 Days of Peace and Music" to an audience many times larger than the estimated 500,000 who actually made it through the gridlocked roads of New York state to Max Yasgur's dairy farm near Bethel.

In his book on the making of the film, associate producer Dale Bell recalls the wild story of the movie that almost wasn't. Underfinanced and overworked, a team of young filmmakers fought traffic, rain, shortages and sleeplessness to record a concert that was more than a concert - "to produce something which would last, which would be different, and which would truly represent the seminal role that the combination of music and lyrics played in the life of the generation of the sixties."

Mission accomplished.

By far the most successful documentary up to that time (and for many years after), "Woodstock" won the Academy Award in 1971 for Best Documentary.

Many people saw both the televised moon landing and the filmed version of Woodstock. Two very different schools of thought began to form about the state and fate of the nation.

Some looked at the multitude of blissed-out kids rocking all night under the flag-marked moon and saw - to borrow from a megahit of that year - "the dawning of the Age of Aquarius," a hint of "the mind's true liberation." Free love, free time, free music. In this new world where all things were possible, Woodstock was a second Eden, as songwriter Joni Mitchellmade explicit: "We are stardust / We are golden / And we've got to get ourselves / Back to the garden."

A great many others were appalled, however. Rather than liberation, they saw license; instead of innocence, they saw decadence. Woodstock was, to them, a repudiation of the values and culture that catalyzed the moon landing, and the American greatness it represented.

I don't think it's too great a stretch to say that these two points of view represent the separate hemispheres of our political world.

One pole envisions a more perfect future, ever more free of constraints whether sexual, or religious, or economic. This is the region of "yes, we can!" At the other pole, people sense the loss of order and tradition, and would like to "make America great again."

Their arguments are at least as old as Rousseau and Hobbes. Yet rarely has a half-century been more deeply marked by this particular thesis and antithesis. Woodstock closed with a howling and distorted rendition of the national anthem by guitar genius Jimi Hendrix, but those chords are still ringing in the likes of Colin Kaepernick and Rep. Ilhan Omar, D-Minn. Do they make your heart soar, or your ears hurt?

In 1969, baby boomers mistakenly believed that the chasm opening around them was generational, and vowed not to trust anyone over 30. Five decades later we see that the boomers were, even then, at war among themselves.

Every weekday JewishWorldReview.com publishes what many in the media and Washington consider "must-reading". Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author