We conservatives say that we favor these decisions not just because we favor the policy outcomes, but because they were right on the law. They reflect the text of the Constitution as its provisions were originally understood by the ratifying public.

We go on to say, typically, that a conscientious judge should not make rulings about the law with their policy preferences in mind. They should not, that is, confuse what the law says with what they think it should say.

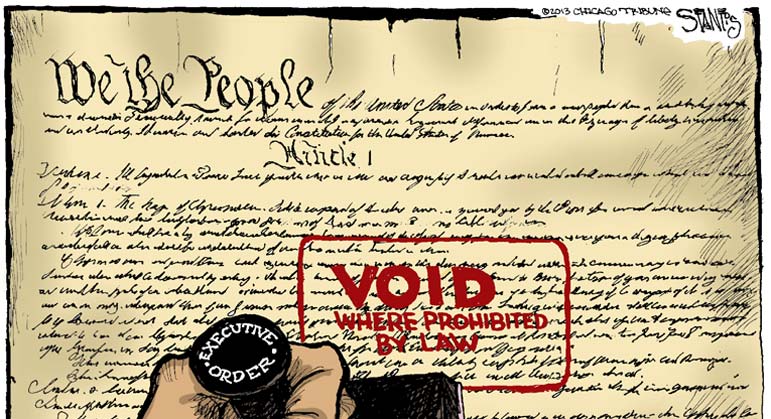

It has not escaped the notice of progressives, though, that conservative legal decisions and conservative policy victories often go hand in hand. It is a pattern that makes them think that conservatives are lying, maybe even to themselves, when they boast about their "neutral" judicial methodology. The conservatives on the court are acting, they say, like conservative politicians who happen to be wearing robes. They are advancing conservative policy goals while putting progressive ones further out of reach.

It is surely true that conservatives' views about what the law should say influence their views about what it does say. Legal philosophies of originalism and textualism do not build an impregnable barrier between the two. But there is also a less embarrassing reason that legal conservatism so often lines up with political conservatism: The US Constitution itself is conservative.

What I mean is not that the Constitution requires the implementation of every sentence of the latest Republican platform or blocks everything in the Democratic one. The Constitution, on any reasonable reading, is clearly compatible with a lot of liberal political victories. But it also, much of the time, pushes in a direction that contemporary conservatives find more congenial than liberals.

Other countries' constitutions include long lists of positive rights that entitle citizens to welfare assistance from the government. Ours doesn't. The Constitution's structural elements — especially the multiple veto points it creates at the federal level — further constrain federal activism.

At the same time, the Constitution, going strictly by its text and the original understanding of its provisions, leaves states with enormous leeway to impose laws regulating morality. Whether one agrees or disagrees with the Supreme Court's decisions on guns and abortion, it is impossible to dispute that the Constitution explicitly protects a right to keep and bear arms and does not have equivalent language about abortion.

The Electoral College and the Senate give rural voters more power than they would have in a pure national democracy. The Constitution's preoccupations, too, are more conservative than progressive: It's written with obvious concern for the preservation of property rights and freedom of contract, and with no obvious concern for sexual freedom.

These characteristics of our constitutional order don't always favor conservatives: Once a liberal federal program has been enacted, for example, the multiple veto points protect it from abolition. But the general tendency is to favor conservatives over progressives, at least as these terms have been understood for the last century.

What's more, everyone, to some degree, already understands this. The conservatism of our Constitution is why people on the right are more likely to call themselves "constitutional conservatives" than people on the left are to call themselves "constitutional progressives."

It's why progressives are much more likely than conservatives to describe the Constitution as fatally flawed or outmoded, and have been at least since Woodrow Wilson's time. It's why, when conservatives seek to amend the Constitution, it is typically to restore an element of the original understanding of it.

And it's why liberals have been attracted to methods of constitutional interpretation that give them free rein to change the meaning of provisions so as, for example, to accord with "evolving standards of decency." Even if conservatives and liberals on the bench were just as avid to reach the policy results they favor, the conservatives would not have to resort to such interpretive methods as much as the liberals do.

Conservatives flock to originalism not just because, in the abstract, it sounds like a compelling account of how laws should be read. They like it because, more than liberals, they generally approve of the Constitution as its provisions were originally understood.

A pious respect for the Founders plays a role in conservative thinking, too. But we might better understand the debates about court decisions and the dueling judicial philosophies underlying them if we recognized that conservatives and progressives have different attitudes toward the Constitution — and that these attitudes are perfectly rational given what each group wants out of government and politics.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Ramesh Ponnuru has covered national politics and public policy for 18 years. He is an author and Bloomberg View columnist.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author