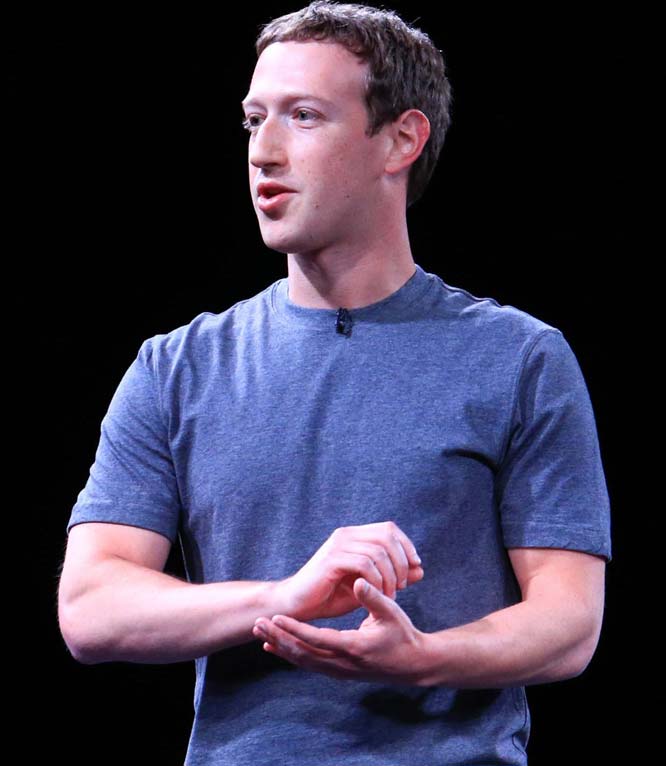

Pau Barrena for Bloomberg

Pau Barrena for Bloomberg

Though, golly, I have so many questions! Like "What is the point of a cryptocurrency with a central authority?" And "Where exactly are they planning to put all the money they intend to hold as reserves to anchor Libra's value?"

But, no, I said we would leave those questions aside. Let's ask a simpler, more visceral question: "Facebook, haven't you got enough problems already?"

As I see it, Facebook is already dealing with two existential threats -- one economic, the other political. The economic problem is that the sheer size of Facebook's social media network is both its greatest strategic advantage and a potentially fatal Achilles' heel. Businesses that depend on network effects enjoy exponential growth early on, as each new user makes the network even more valuable to everyone else. But if the network ever starts to shrink, that same process can abruptly reverse into a high-speed implosion.

Facebook's political problem is that too many people hate it. Which naturally makes the first problem worse.

Autocratic governments hate Facebook because they worry it's a good tool for organizing to overthrow autocratic governments. European governments hate Facebook because of privacy concerns and because it's not European. Journalists hate Facebook because it has siphoned off the ad revenue that used to go toward paying journalists. The American left hates Facebook because it thinks the company's news algorithms helped put President Trump in the White House. The right hates Facebook because Silicon Valley skews very liberal, and it shows.

When the left started muttering loudly about breaking up Facebook, conservatives -- instead of rallying for property rights -- got quiet or, worse, joined in. On Wednesday, Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., introduced legislation to strip the immunity that platforms such as Facebook enjoy from liability for user-posted content, a rule that would effectively be the death knell for Facebook and a host of other tech firms.

Businesses tend to ignore political problems for too long, because those aren't the sorts of problems that businesses are best at solving. But in this case, becoming more of a political flashpoint is Facebook's biggest business problem, because partisan rancor makes it much more likely that the network effects will start to reverse, and that governments will help the process along.

Facebook should be focused on fighting for its life in Washington and Brussels. Instead, it's still merrily thinking about extending its industry dominance.

As a business school case, the strategy isn't crazy: If Calibra works, it will provide Facebook with a major revenue stream beyond advertising dollars and make it harder for people to leave the platform. But shoring up that Achilles' heel won't help if regulators cut off Facebook at the knees, as is likely to happen if Libra and Calibra go even partway toward achieving the audacious goals set out in the white paper: Billions of accounts! Peer-to-peer processing of transactions, without a central intermediary!

For all Facebook's talk about helping the unbanked, with Calibra the company seems intent on becoming a major competitor of the existing banking system. And Libra, in which Facebook is heavily involved, will be competing with the governments that issue the currencies those banks trade in. Governments tend to resent private institutions that infringe on their prerogatives. They also tend to scrutinize rivals to the banking system as, well, banks, and Facebook is both too big and too famous to squeeze through some cute regulatory loophole.

Being treated like a bank would mean being subject to the sort of intrusive regulation that Facebook has so far managed to avoid. It would identify Facebook with an industry even more hated than the tech giants. And it would give Facebook's political enemies one more policy lever -- a very large one -- to use against the platform. The only way this could possibly improve Facebook's prospects is if the company's becoming a payment vendor made people not just use Facebook more, but like it more.

So before they go forward, I invite Facebook executives to type the words "I love you like my bank" into Google. They'll find exactly one hit: this column. There's a reason those words have apparently never before been strung together in the English language. It is the same reason that Calibra is folly.

Every weekday JewishWorldReview.com publishes what many in the media and Washington consider "must-reading". Sign up for the daily JWR update. It's free. Just click here.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Megan McArdle is a Washington Post columnist who writes on economics, business and public policy. She is the author of "The Up Side of Down." McArdle previously wrote for Newsweek-the Daily Beast, Bloomberg View,the Atlantic and the Economist.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author