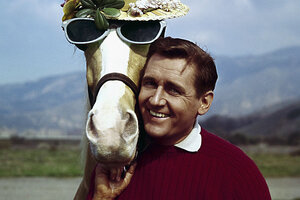

Readers of a certain age will remember the iconic television series "Mr. Ed." The title character, a talking horse, entertained viewers by routinely displaying more insight and common sense than its owner, Wilbur. It's elucidative to reflect that the inspiration for Mr. Ed may have come from a real-life horse that, however briefly, captivated the world with its astonishingly human intellect.

In September 1904, Scientific American published a story about Clever Hans, a stallion trained by its owner, Wilhelm von Osten, to solve rudimentary arithmetic equations by tapping out answers with its hoof. Understandably skeptical experts came to test the brainy horse; they went away convinced of its remarkable talent.

Further investigation indicated a less preternatural explanation. The horse simply possessed "horse-sense." It discerned the correct answer by reading body language signals communicated unconsciously by the examiners. These included blinking and shifting eyes, head movements, lip configuration, posture, hand movements, jaw tension and breathing patterns.

Indeed, Hans could no more count than Mr. Ed could talk. But the solution to the mystery was only revealed by way of a testing technique that is this week's addition to the Ethical Lexicon:

Double-blind | adjective

Describing a test or trial in which information that might influence the behavior of the examiner or the subject is withheld until after the test.

Procedural flaws that became clear in hindsight might have been caught earlier through observation and inquiry. Why did Hans correctly answer questions only when the questioner knew the answers? Why did successful results depend on the proximity of the owner?

The examiners did not ask these questions. It never occurred to them that their own knowledge of the answers might have influenced the responsiveness of the horse.

Eventually, science caught up with them. In 1998, researchers at Israel's Weizmann Institute of Science made the bewildering discovery that quantum particles behave differently when observed than they do unobserved. It seems engineered into the mechanics of the universe that the mere act of observation changes the nature of our reality.

Philosophers, psychologists and sociologists have eagerly applied the same "observer effect" to human behavior. No matter how committed we are to remaining objective, unconscious bias can poison the process of investigation and thereby render unreliable conclusions.

On the one hand, nonverbal cues can project meaning quite different from what we intend. On the other hand, expected results cause us to skew the data we collect and distort our perception of what we observe. Despite our best intentions, the search for truth may end up reinforcing falsehoods and misconceptions.

The good news is that awareness of cognitive bias enables us to protect against observer effect. And although double-blind procedures are most relevant in the laboratory, we can apply the underlying principles to ensure intellectual integrity in society and in the workplace:

• Create layers of separation between seekers and gatherers of information.

• Allow subordinates to discuss and debate unsupervised by leadership.

• Appoint a devil's advocate to search for weak points in any proposal or argument.

These time-honored methods are elements of an overarching strategy for thwarting cognitive bias: Create a circle of trust.

Two thousand years ago, the revered sage Hillel the Elder encapsulated the mindset that protects us from misperception and misinformation: "Do not trust yourself until the day you die."

With this pithy aphorism, Hillel warns against the dangers of rationalization and unconscious bias. He also alerts us to the value of trusted advisers. Precisely because we may not recognize when our objectivity might be compromised, we need to check in with friends or colleagues whose judgment is sound and whom we can count on to tell us the truth.

Mr. Ed's owner, Wilbur, might have taken this advice himself — especially once he realized that no one else ever heard his horse talk. It's OK to listen to the voices inside your head, but no matter how clever they sound, seek reliable confirmation before giving them free rein.

Previously:

• A Healthy Diet for the Brain Promotes Ethical Clarity for the Mind

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Rabbi Yonason Goldson graduated from the University of California at Davis with a degree in English, which he put to good use by setting off hitchhiking cross-country and backpacking across Europe. He eventually arrived in Israel where he connected with his Jewish roots and spent the next nine years studying Torah, completing his rabbinic training as part of Ohr Somayach's first ordination program. After teaching yeshiva high school for 23 years in Budapest, Hungary, Atlanta, Georgia, and St. Louis, Missouri, Rabbi Goldson established himself as a professional speaker and advisor, working with business leaders to create a company culture built on ethics and trust. He has published seven books and given two TEDx Talks, is an award-winning host of two podcasts, and writes a weekly column for Fast Company Magazine. He also serves as scholar-in-residence for congregations around the country.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author