WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. — Ally Wilkinson did not plan to spend her senior year at Wake Forest University doing something strikingly stressful: juggling a full-time job with a global consulting firm while also taking classes to finish her degree.

Like many in her generation, Wilkinson demands that her job allow for life balance and overall wellness, she said, including time for exercise and socializing. When she tells her bosses she has a class or a meeting outside of work, for example, they tell her to do what she needs to do. Even so, she said, "they honestly get annoyed."

Wilkinson and other new college graduates are starting careers at a time of sharp generational disconnect over how the workplace should operate and how younger employees should inhabit it. In response, many colleges are rewriting the way they prepare students for jobs - and life.

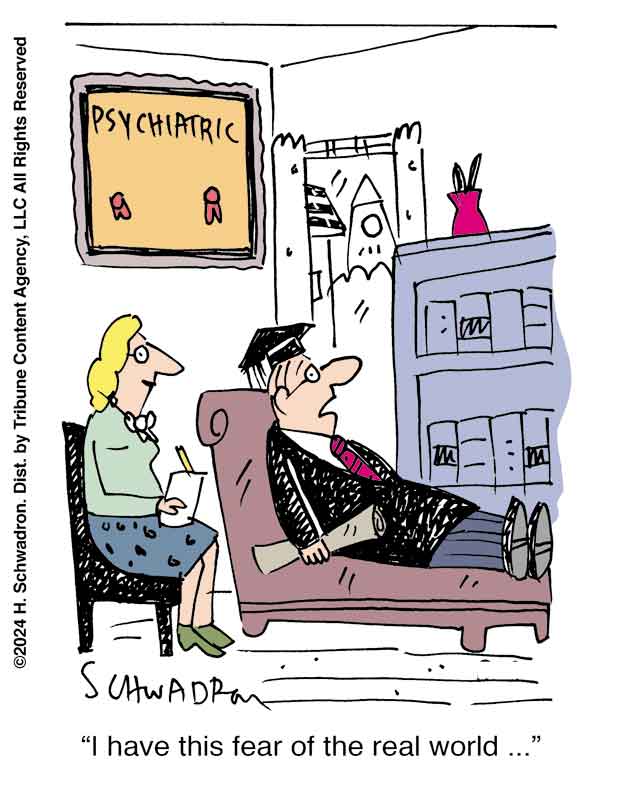

Some of this adjustment is the result of changes colleges have noticed in their students: Because they lost key in-person experiences to covid and often continued learning on Zoom, new grads and other Gen Zers frequently haven't had practice at speaking up in large groups, asking for help or responding to authority figures.

This generation, typically those born between 1997 and 2012, also has grown up with threats such as covid, school shootings and the impact of social media, including bullying and self-doubt sown by pop-culture pressures. This has led many Gen Zers to prioritize their mental well-being, according to research and experts who work with them. Surveys repeatedly show that a large percentage of Gen Zers struggle with well-being and want to be able to talk about it at work.

At the same time, "there are some students who get stressed out easily and prioritize taking care of themselves over being accountable," said Briana Randall, executive director of the Career & Internship Center at the University of Washington.

The result is friction around how much employers should bend to individual needs. As young workers vocalize their expectations for work-life balance, they are labeled by some people as "unprofessional" and "entitled."

A 2024 Intelligent.com survey of managers found 51 percent said they were frustrated by Gen Z employees - and 27 percent would avoid hiring them.

For colleges - judged by how well they prepare students for the workforce - this means it's not enough to host job fairs or to assist with résumés, cover letters and mock interviews. Students need explicit instruction on old-fashioned tasks such as composing a professional email (no emojis or exclamation points) and work etiquette (how to break in and out of conversation). They also need to learn how to react to workplace demands, said Shannon Anderson, a sociology professor at Roanoke College in Virginia who teaches a course called Internship Planning and Prep.

With Gen Zers having missed out on social learning and been "given a lot of grace" around turning in work late in high school and even college, she said, "when somebody comes in and says, 'You have to get things in by the deadline,' they feel angry." She admits to blanching when students declare they "need a self-care day" but says they need to be taught about professional expectations.

She does that by providing extremely explicit information. For a generation accustomed to step-by-step advice on TikTok and Instagram, knowing what to do in detail offers relief. Jennifer Burch, a senior planning a career in public health, took Anderson's class. Just because her generation grew up with the internet, she said, older people think "that we know everything about how to correspond with another person via email or on the phone. You know, some people don't even know how to answer phones."

Information that another generation might grumble is common sense shows up in for-credit career classes on campuses like Roanoke's. Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore offers two dozen, and Wake Forest has five.

Around the country, 486 schools teach a set of career competencies developed by the National Association of Colleges and Employers, or NACE, and many weave them into academic courses. While most of these focus on workplace skills - such as the importance of being present and prepared - one of them, called career and self-development, delves into mental health and well-being. It explores "how a student thinks through their whole self and what it means to have work-life balance," said NACE President and CEO Shawn VanDerziel.

The notion that you are more than your job is important but has rarely been a point of emphasis on campus. That's changing. Johns Hopkins, for one, has reframed its approach from helping students find a job to helping them seek life satisfaction.

"What Gen Z is asking for is, 'Provide me a work environment in which I can work and feel fulfilled,'" said Farouk Dey, a vice provost who in 2018 began flipping the campus's career counseling to focus instead on "life design."

Today Hopkins's Imagine Center, which opened in 2022 adjacent to the football stadium, features free coffee and hot chocolate, comfy modular furniture and enclosed workspaces with words like "HYGGE" (the Danish concept of coziness) and "'IMI OLA" (Hawaiian for seeking your best life) etched in frosted letters on glass.

Instead of pressing students about what they want to be, then creating "very linear pathways toward that," Dey said, staffers seek to uncover what makes students curious and help them investigate those paths, including whether a passion will become a job - or an avocation.

This is new for an elite university that typically sends graduates straight into finance, consulting, tech, government, engineering and health care or to law and medical schools. "We're trying to detangle their identity from the outcome that they come in here saying is 'success,'" said Matthew Golden, who leads the Life Design Lab at the center.

This contradicts old-style career coaching in which, he said, "you told everyone you're going to work on Wall Street, so let's get you to work on Wall Street."

This broader view of success seems wise in a tough job market. It's too soon to know whether the U.S. faces a version of the 2007 financial crisis. But new data on the Class of 2025 from the online job platform Handshake shows the average number of applications for each posted job is up 30 percent from a year ago. Data also shows that small businesses with 250 employees or fewer this year received 37 percent of applications, more than medium and large employers and a greater percentage than for the Classes of 2022, 2023 and 2024.

At the University of Washington, 12 staffers at the Career & Internship Center serve 25,000 undergraduates, 9,000 graduate students, and recent alumni. Randall, the executive director, said employer attendance for the spring job fair was down more than 25 percent. She canceled a virtual job fair for April after only two businesses registered to attend.

Teaching students to center their values, said Dey, of Johns Hopkins, can help them pivot from a government job to a nonprofit, or from a corporation to a start-up. It makes turbulence something, he said, that "our students are fully capable of surviving."

One recent morning at the Johns Hopkins Imagine Center, Alex Kroumov, a soft-spoken sophomore from Chandler, Arizona, majoring in biomedical engineering and applied math, ate pizza as he looked for summer internships. He said he'd applied to 50 and got no offers.

Graduation is two years off, and while Kroumov feels the current uncertainty, he said it's not gutting his expectations for his work life. He still wants, as many Gen Zers do, to do work that "is for a good, or like, morally just cause," he said, and in an environment where attention to mental health is part of the culture.

Even as the job market tightens, Gen Zers - who are particularly familiar with uncertainty - seem strikingly committed to their well-being. They balk at superficial compliance to land or keep a job.

"It's not that we don't care about the work, or we're not interested in the work. We are just now valuing our life at the same level," said Burch, the Roanoke College senior. She sees too much focus on "nonissues, like, 'Oh, what she or he is wearing. Is it not formal enough?''' she said.

One challenge for employers is that businesses face competition, said Nick Bayer, CEO of Saxbys, which during the pandemic transformed from a fast-casual restaurant into a campus-based education company giving students real-world work experience.

"Those young people who are like, 'Employers are going to have to change to us, like, we're just a different generation,'" he said, are missing the fact that, whether you are the newest employee or a veteran, "everyone has to do what's necessary to get the job done."

Wake Forest professor Patrick Sweeney teaches a course called Foundations of Leadership to undergraduates. He and colleagues found, in a 2024 study, that young workers have these specific values around work: "to be included in decision-making, kept informed, given personalized attention, provided flexibility in the work schedule, given a clear growth path, provided an opportunity for work-life balance, and to be part of an organization that does good."

Sweeney hears executives grouse that Gen Zers have "to earn their stripes" before being listened to. He pushes back. "It is not like we are treating them like snowflakes," he said. "If we can provide them the flexibility and we can set boundaries where they do have a work-life balance, we'll probably get the best out of them and they'll stay on our team."

Wilkinson, the Wake Forest senior already working full time, appreciates her employer's flexibility. She said her team of co-workers has "a culture of 'you get your work done,'" and is less concerned with specific hours.

Still, she hears older workers complain about younger ones. What they miss, she said, is that younger workers have skills, including using artificial intelligence, that make them "very efficient." Tasks that once took an entire workday now "can take me 45 seconds," she said of using AI. "I can utilize those things that, frankly, no one else on my team can."

Professor Heidi Robinson, who had Wilkinson as a student, said there are just practical skills that college-age people haven't had experience with. That's why her course delves into details such as how to behave at "an eating meeting" or when and how to send handwritten thank-you notes.

She does this, she said, because she sees this generation "as a practical group, so they want to do it right." She wants to offer support - and hopes others do, too.

"We have to have some empathy for our new young professionals," said Robinson. "We've got two different generations coexisting in the world in the same office, in the same Zooms - and everyone has learned 'work' a little bit differently." This report is a product of The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author