He avoided uttering the three letters of his supposed employer, a renowned intelligence agency. His presence was required "up river," he'd tell colleagues. He needed to see "agency people."

Those who worked with Levin at Daniel Morgan - a fledgling school that offers graduate programs to aspiring spies and diplomats in downtown Washington, D.C. - did not investigate his credentials. He had convinced former CIA operatives and national security veterans that he was one of them.

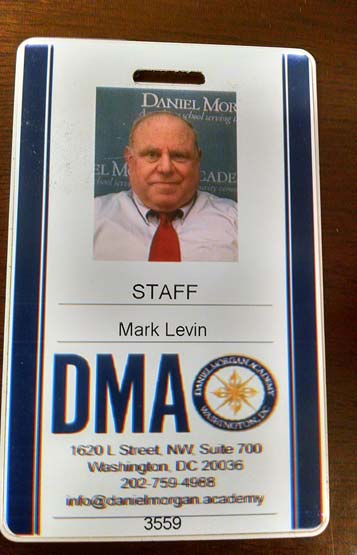

Now a $150 million lawsuit accuses Levin, 72, a former special adviser to the school's president, of inventing a clandestine career to manipulate three young men who worked at Daniel Morgan into sexually abusive encounters. Levin convinced the men that naked, physical inspections would determine their futures at school and their careers in the intelligence world, the alleged victims said.

"All of it sounded credible, and I believed it because he was the boss of the school," said a 24-year-old Daniel Morgan employee who lives in Falls Church, Virginia, and is one of the three men suing Levin and the school in D.C. Superior Court. The men have been granted anonymity by a judge, and The Washington Post generally does not identify alleged victims of sexual abuse.

Levin, who was not paid by Daniel Morgan, did not return phone calls seeking comment. He has not been charged with a crime related to the accusations. But the lawsuit has raised questions about his past and how carefully he was vetted by officials at Daniel Morgan and, before that, at another Washington graduate school, the Institute of World Politics.

Levin was already working at Daniel Morgan when Joseph DeTrani arrived as president in January 2016. After the allegations surfaced eight months later, the school launched an internal investigation, reported the accusations to police and fired Levin. DeTrani, a former CIA officer who carried the rank of ambassador while serving as a special envoy for six-party talks with North Korea, said he thinks Levin is an impostor.

"I checked him out with a number of agencies in Washington and in the intelligence community, and no one had anything on him," said DeTrani, who left Daniel Morgan last week for reasons unrelated to the allegations. He called Levin "a sick, sick man. He conned these young men into believing something he was not."

And he may have deceived the intelligence veterans he mingled with and worked alongside.

"I know people think it's weird and could say, 'How would he be able to con a bunch of spies?' But it's a large community, and you might figure he has a role in something you're not aware of," said Linda Millis, a former CIA official who until March served as Daniel Morgan's executive director. "Other spies, when we socialize with each other, we don't ask each other about our backgrounds."

Levin represented himself as an old hand of the national security establishment, former colleagues said.

Military records show that he served in the Army Reserve from 1966 to 1971 during the Vietnam War, and was awarded a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star Medal. He graduated from the University of Miami in 1972 and earned a law degree from Florida State University in 1975, school officials said. In the early 1990s, Levin ran a restaurant consulting company, according to Florida business records.

Then he moved to Washington, where he became a kind of unpaid, unofficial adviser at the Institute of World Politics, a national security graduate school, former employees said.

In the late 1990s, Levin began attending the institute's public lectures. Then he started handing over checks to pay for the tuitions of certain students, though the source of the money was a mystery, said one former senior school official who feared retribution if identified by name.

In 2009, he was arrested on a misdemeanor charge of "concealing merchandise" in Fairfax County and later pleaded guilty, agreeing to perform community service at a library in Alexandria, according to court records. It is not clear whether anyone at the institute knew about the incident.

"Mark Levin was an occasional visitor to the Institute of World Politics for about a decade, ending in 2013," the school said in a statement. "He did not serve in any advisory capacity."

Levin networked with former spies by attending lunches and other events sponsored by the Association of Former Intelligence Officers (AFIO) and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Society.

Elizabeth Bancroft, the director emeritus of the AFIO, said Levin brought students from the institute to association lunches, from about 2009 to 2012, at a Tysons Corner hotel. The association asked him to join as a paying member - which would have required him to submit forms detailing his career - but Bancroft said Levin always demurred.

In 2013, Levin tapped a crew of current and former institute staffers to work at a VIP reception at an OSS Society dinner honoring retired Navy Adm. William McRaven, who helped plan the attack that killed Osama bin Laden.

"We were just checking people in, and Mark spun it as, 'You're going to provide security for the heads of the CIA and other leading heads of the intelligence community,' " said a former institute employee who served as one of Levin's "security officials" that night and later went on to work at Daniel Morgan. He requested anonymity for fear of retribution. "I remember Mark walking through the VIP room, with the presence of authority, shaking hands and saying hi to some people."

But Levin's relationship with the OSS Society came to an abrupt end. "After we discovered that Levin snuck unregistered people into our dinner with fake badges," Charles Pinck, the president of the group, said in a statement, "we banned him from attending our events."

The CIA said that it generally does not comment on whether someone previously worked for the agency. In a statement after the lawsuit was filed, the agency condemned anyone who poses as a CIA officer to commit "abhorrent acts against young people or otherwise engages in illegal activity."

Langley has dealt with espionage wannabes before. Wayne Simmons, a former guest analyst for Fox News, was sentenced to prison last year for falsely claiming he had spent decades as a CIA operative. TV game-show impresario Chuck Barris, the creator of "The Dating Game" and "The Newlywed Game" and host of "The Gong Show," claimed to be a CIA assassin in his autobiography - an assertion the agency flatly denied.

But those impostors were not surrounded by former spies, as Levin was.

Linda Strating, Daniel Morgan's former director of strategic alliances, recruitment and student services, said the allegations about Levin surprised her.

"Mark is incapable of harming a fly," she said. "He's a very thoughtful soul."

But she, too, said she knew little about Levin's career. All he told her, she said, was that he had been a helicopter pilot during the Vietnam War and was injured while "getting wounded pilots out of dangerous places."

The Arlington man first met Levin in 2012 at an orientation for new graduate students at the Institute of World Politics, a program housed inside a red-brick mansion less than a mile from the White House.

Levin, a bald man with a slight hobble, told the 21-year-old that he had already "done some collection" on him and was keeping a "dossier."

Levin said that he had worked for 47 years in intelligence and counterterrorism and that he was recruiting students for his clandestine, unnamed organization, the Arlington man said. Levin told him to stay in touch and gave him his cellphone number and his email address, which contained the word "selenium."

"Mark claimed . . . that if you were hired as an agent, you would be assigned an email based on an element from the periodic table," said the Arlington man, now a Daniel Morgan administrator suing the graduate school and Levin. "There was an air of legitimacy around it. He walked around IWP like he was in charge."

At the institute, Levin had no official job or salary. But he functioned as a counselor to the school's founder and president, John Lenczowski, and claimed he represented a donor willing to give at least $1 million to the institution once it got accredited, former officials said.

But after the institute earned its accreditation, neither the money nor the donor's identity materialized. Lenczowski, who served on President Ronald Reagan's National Security Council, declined to comment.

By late 2012, the alleged victim said, Levin told him that if he wanted to remain a candidate for Levin's covert group, he needed to avoid marriage, children, sexually transmitted diseases and relationships with Muslim women. Levin warned him, he said, that his "guys" would constantly watch him and that if he didn't follow instructions, he would be blacklisted from government jobs.

The Arlington man - whose mother is a former prosecutor in southern Virginia - said he believed Levin. He saw him pal around with other former spies at various AFIO and OSS social events. According to the lawsuit, Levin created the impression he had personal relationships with former CIA directors John Brennan and David H. Petraeus.

Brennan and Petraeus, through spokesmen, said they do not recall ever meeting Levin.

Then, Levin began inviting his protege back to his Arlington apartment building to practice drawing a weapon - shirtless. Soon, the man said, Levin began fondling him and giving him prostate exams, telling him the inspections were key to his recruitment. Levin also bathed him in the shower under the pretext of helping him with his hygiene, according to the alleged victims' lawsuit, which was filed by lawyers Tamara Miller, a former Justice Department deputy chief, and Peter Masciola, a retired brigadier general.

Although Levin told him that he was free to refuse, the Arlington man said he did not want to imperil his candidacy for the clandestine organization or risk losing out on government jobs.

About the same time, Levin had persuaded a second young student at the Institute of World Politics to get in the shower, under similar pretenses, the lawsuit says.

In 2013, institute officials received student complaints about Levin, according to Owen T. Smith, chairman of the institute's board of trustees.

"The guy was strange and had an uneasy presence on campus," Smith said. "There were certainly questions about who he was and why he was there."

Smith said the board looked into Levin's background but could not confirm he had ever worked in the intelligence community. As a result, Smith said, Levin was banned from the school.

He retained the trust of one institute board member: Abby S. Moffat, the chief executive of the Diana Davis Spencer Foundation, which focuses on bolstering U.S. national security.

In 2013, Moffat resigned as an institute board member and established a new intelligence graduate school, bringing Levin with her.

"Abby was on the board at the time of our investigation" into Levin, Smith said. "I don't know how she could not have known about it."

Moffat denied that was true. "I can state unequivocally that at no time during those days was I aware of any investigation by IWP into Mr. Levin's intelligence background," she said in a statement, "and I had absolutely no information that he was engaged in the conduct that he is now alleged to have committed."

Her foundation gives Daniel Morgan $7 million a year and is the school's primary revenue source.

In the beginning, the new school was called National Security Enterprise, and Levin, the lawsuit says, was fond of telling people who suggested it to him: James R. Clapper Jr., then President Barack Obama's director of national intelligence.

Clapper, through a spokesman, said he does not know Levin.

By early 2014, Levin had hired two of his alleged victims from the Institute of World Politics as employees at National Security Enterprise.

In June 2014, National Security Enterprise was renamed in honor of Daniel Morgan, a renowned general during the American Revolution. The school hired its first president, Marion "Spike" Bowman, a former deputy national counterintelligence executive. He now serves on Daniel Morgan's board of trustees and said in a brief interview that he "didn't know anything about [Levin's] history."

The school's original staffers said they viewed Levin skeptically but figured Moffat had vetted him.

Levin controlled how Moffat's foundation money would be spent, according to Dick Coffman, a retired CIA officer and the school's No. 2 official from summer 2015 to March 2016. Levin approved the hiring of faculty members, courses, even the pens for college fairs, Coffman said. Levin organized Daniel Morgan's relocation to the seventh and 10th floors of an office building at 1620 L St. in Northwest Washington.

"Abby was the sole source of funding. But he ran the school. He had complete - and I mean 'complete' in the full meaning of the word - control over the budget and funding," said Coffman, who believes the reason his contract was not renewed was that he questioned Levin's authority.

Levin pushed to make tuition free, Coffman said, and hired interns at about $20 an hour when similar organizations paid far less. He said Levin promoted several interns to high-paying administrative jobs that should have gone to more seasoned candidates. Two of the lawsuit's plaintiffs, for instance, were earning salaries of $55,000 and $85,000.

Levin constantly spoke of his "black operations" in Nigeria, Poland and Israel, Coffman said. "He told people he was out every night hunting Arab and Iranian terrorists on the streets of Washington," he said.

Millis, who followed Coffman as the school's executive director, grew worried by Levin's boasts.

"When I got there, he told me: 'I'm a trained assassin. I've killed 38 people.' But then he would say, 'Really, I've just put them in a coma,' " Millis recalled. "I'm not the only person he'd say this to. People would say, 'Oh, Mark and his 38 people.' "

When the Falls Church man applied for his internship in July 2016, Levin told him "The Watchers" or "my guys" had been surveilling him.

"Then, Mark told me: 'I've killed 38 people. We have people killed all the time. And we cover our tracks,' " he said. "I was intimidated."

Well before the allegations of sexual abuse surfaced in August, DeTrani, Daniel Morgan's president, had already started investigating Levin's past. It was then that DeTrani learned that a graduate school devoted to national security had not done background checks on its employees. Among those who hadn't been scrutinized: Mark Levin.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author