Andrew Harrer for Bloomberg

Andrew Harrer for Bloomberg

The court declined to take the case of Kathrine McKee, who accused Cosby of raping her more than 40 years ago. She sued after Cosby's attorney leaked a letter that she said distorted her background to "damage her reputation for truthfulness and honesty" and to shame her.

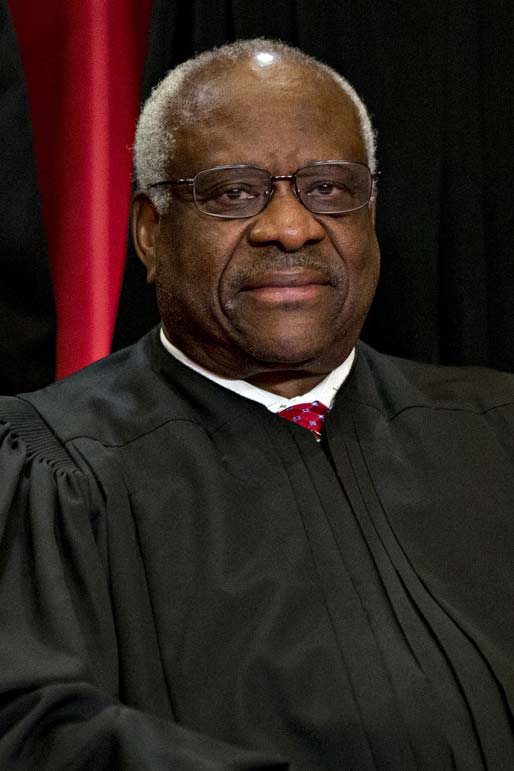

Thomas said he agreed with his colleagues not to accept McKee's "factbound" appeal.

But he launched a detailed critique of the landmark libel ruling, which he said was a "policy-driven" decision "masquerading as constitutional law." No other justice joined his concurrence.

But President Donald Trump has also expressed support for making it easier to sue for defamation, and during the campaign - and afterward - he complained about "hit pieces" in The Washington Post and New York Times.

"I'm going to open up our libel laws so when they write purposely negative and horrible and false articles, we can sue them and win lots of money," Trump said during the campaign. Over the weekend, he complained about a "Saturday Night Live" skit and wondered about "retribution."

Some media law experts expressed concern over Thomas' declaration.

Jonathan Peters, a professor of media law at the University of Georgia, said New York Times v. Sullivan "is essential to our modern understanding of press freedom."

Peters said the ruling "had the immediate impact of emboldening news organizations to cover the civil rights movement more forcefully - and later the Vietnam War and Watergate."

But Thomas and Justice Antonin Scalia have said the court may have intruded into a space in which it was not needed.

"We should not continue to reflexively apply this policy driven approach to the Constitution," Thomas wrote. "Instead, we should carefully examine the original meaning of the First and Fourteenth Amendments. If the Constitution does not require public figures to satisfy an actual-malice standard in state-law defamation suits, then neither should we."

The media for decades has depended on New York Times v. Sullivan as a shield for reporting on public figures. But Thomas said Justice Byron White had also expressed concern after he was in the majority in the case.

"Like Justice White, I assume that New York Times and our other constitutional decisions displacing state defamation law have been popular in some circles, 'but this is not the road to salvation for a court of law,' " Thomas wrote, quoting White. ". . . We did not begin meddling in this area until 1964, nearly 175 years after the First Amendment was ratified. The States are perfectly capable of striking an acceptable balance between encouraging robust public discourse and providing a meaningful remedy for reputational harm."

The case the court declined to take is McKee v. Cosby.

In September, Cosby was sentenced to three to 10 years in prison for sexually assaulting a different woman in 2004.

(COMMENT, BELOW)

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author