|

|

Jewish World Review / May 8, 1998 / 12 Iyar, 5758

William Pfaff

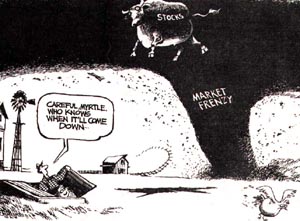

PARIS -- A friend said to me the other day that the word

"crash" no longer is part of the American vocabulary. We

only know stock market "correction," and corrections have

just to be waited out.

He explained to me that the stock market only goes up,

because immense popular and political interests, as well as

corporate interests, are today committed to its only going up.

His implied argument was that the American government has

no choice but to make it go up.

It struck me, as he was speaking, that this might have been

what Jay Gatsby was saying to his friends during the luxurious

summer of 1929, a few months before Gatsby disappeared

off the end of that dock in West Egg, on Long Island Sound, or

went back to the Middle West -- if it was the Middle West --

which, for Gatsby, would have been worse. But I am a child

of the Depression.

It also struck me that this belief that Washington has the

power to make the market perpetually go up contradicts

what everyone in the markets has been saying during the last

few years, which is that in the age of globalization and

liberalization, governments are no longer relevant; they

should get out of the way of the market.

We have recently seen crashes in the Asian markets. Most

Americans, including President Bill Clinton, seem confident

that the United States will not suffer from what happened in

Asia. The general belief is my friend's belief, that the

American economy now has been transformed into one

which can only grow.

This seems to me a very romantic view of globalized

American capitalism, which by objective measurement has

not proven notably more efficient (nor even more globalized)

than the post-World War II economy. The level of

international exchanges is little larger today than it was at the

end of the 19th century, when the industrial countries

functioned on the gold standard -- their version of a single

currency.

Since the end of fixed exchange rates in 1971, the major

industrial economies have mostly seen lower growth, higher

unemployment, and lower productivity growth than before.

They experienced a sharp deterioration in overall

performance in the 1980s and early 1990s, as John Eatwell,

president of Queens' College, Cambridge notes in a new

Swedish Foreign Ministry assessment of globalization. Growth

of GNP in the major industrial countries during the

1983-1992 period was about half that of 1964-1973. Growth

of GNP per capita during both periods was lower than in the

immediate postwar period in 18 out of the 20 OECD

countries.

It is true, as President Clinton recently said, that "over any

given 15- or 20-year period, the stock market has always

outperformed...government bonds." One reason this is true is

that world war and cold war drove the economy. As recently

as the Reagan administration, the U.S. gave itself a solid

stimulus of Keynesian deficit spending. Britain, the other

leading free-market economy, enjoyed a bracing devaluation

in 1992 (the effects of which now are wearing off).

The other reason Mr. Clinton is right about the stock market

is that you knowingly accept a fixed return from bonds

because your money is safe. Stocks may outperform bonds on

the way up, but stocks can also ruin you by going down. It's all

in the timing.

The United States has been the principal beneficiary of

globalization. The largest net international transfer of

resources between 1983 and 1992 was to the United States,

at an average rate of $100 billion per year. After 1992 there

were big net transfers of both portfolio and direct investment

to Asia and to Mexico as a result of market liberalization

there, leading up to financial crisis in both places.

The fact that the American investors escaped major losses in

those crises, thanks largely to American-promoted IMF

rescues, has added to Americans' sense of invulnerability in

the new economy. This undoubtedly is influenced by the

parallel American sense of political and military

invulnerability. The same friend said to me, "Do you think

any other empire has ever been so powerful?"

I said that in sheer physical power, the answer obviously is no.

But Greece, Rome, the great Arab empire of the 8th to 12th

centuries, Spain and Portugal, Britain, France --- all left more

profound and even positive cultural marks on the foreign

societies they dominated than the United States has done.

America's global hegemony is only a few years old, and the

sustained American world engagement goes back only to

1941. We will see what comes next. It is not unreasonable to

argue that we today experience the peak of America's

influence. But even if that is wrong, I cannot believe that the

American market can only go up, which would mean that we

have found the alchemists' stone --- an unlikely story, as Jay

Gatsby himself would have acknowledged.

I would stick with an older American assumption, that if

something seems too good to be true, it probably

Things can only get better and better!

Things can only get better and better!

5/5/98:

Racial, ethnic, national barriers disappearing

4/21/98: A terrifying synthesis of forces spawned Pol Pot's regime

4/19/98: Russian-German-French structure of consultation is good development

4/16/98: Violence in society comes from the top as well as the bottom

4/13/98: Clinton's foreign policy does have a sunny side, too

4/8/98: Public interest must control marketplace

4/5/98: Great crimes don't require great villians

3/29/98: Authority rests on a moral position, and requires consent

3/29/98:Signs of hope in troubled Russia

3/25/98: National Front amassing power

3/23/98: NATO's expansion contradicts other American policies

3/18/98: The New Yorker sought money, but lost it

3/16/98: America's 'strategy of tension' in Italy

3/13/98: Slobodan Milosevic may have started something that can't be stopped