|

|

Jonathan S. Tobin

Re-writing "Anne Frank" - A distorted legacy

Re-writing "Anne Frank" - A distorted legacy

IN THE UPSTAIRS of my parents' house  there was an entrance to a small crawl

space covered by a small bookcase that could be pulled out of the wall to

reveal the storage area. After reading Anne Frank's "The Diary of a Young

Girl" as a youngster, I was never able to look at that bookcase in my

sisters'

bedroom without thinking of Anne and the other million and a half Jewish

children who perished in the Shoah.

there was an entrance to a small crawl

space covered by a small bookcase that could be pulled out of the wall to

reveal the storage area. After reading Anne Frank's "The Diary of a Young

Girl" as a youngster, I was never able to look at that bookcase in my

sisters'

bedroom without thinking of Anne and the other million and a half Jewish

children who perished in the Shoah.

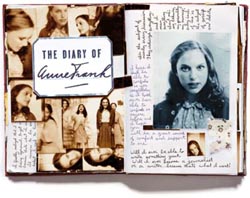

Anne Frank's account of her two years and two months spent hiding in the attic of a factory building (the entrance to which was covered by a false bookcase) is one of the world's most famous and beloved books.

This past week, I spent some time re-reading the "Diary" in the "Definitive Edition" published in 1995. I went back to "The Diary" after recently seeing the New York revival of the 1955 Broadway play based on the book.

Most of the critical reviews about the play have little to do with the merits of the current production. Instead, the revival has rekindled the original controversy over the adaptation of the diary into a play and then a feature film, which, in the words of writer Cynthia Ozick, "bowdlerized, transmuted, traduced, reduced...infantilized, Americanized, homogenized, sentimentalized, falsified, kitschified," Anne's story.

Ozick, whose brilliant scathing denunciation of the play and movie was published in The New Yorker magazine last October, was taking up the cause of another famous Jewish writer, Meyer Levin (1905-1981), who spent the last 30 years of his life obsessed with the distortion of the diary.

Meyer Levin's obsession

Shortly after "The Diary" was first published in Europe, Levin, a passionate Zionist who was by then a well-known author and war correspondent, helped get the book an American publisher and offered to adapt it for stage and screen. He began a short-lived friendship with Anne's father Otto Frank, who was the only survivor of the group who lived in the secret annex.

After helping Frank find contacts in America and being promised the adaptation rights, Levin was pushed aside. His theatrical version of "The Diary" was rejected by Frank and his advisers on the grounds that it was "too Jewish."

Acting under the direct influence of left-wing playwright Lillian Hellman, among others, Frank and his chosen producer Kermit Bloomgarten opted for a less Jewish, more "accessible" Anne for the stage. Infuriating Levin, who felt he and Anne were both being cheated, they gave the assignment to Hollywood screen writers Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett, whose most famous movie script remains Frank Capra's 1945 classic "It's A Wonderful Life."

Eight drafts later and with much play doctoring by that loyal Stalinist Hellman, Goodrich and Hackett produced a Holocaust play in which the fate of the Jews was pushed into a corner to make way for a coming-of-age story about a cockeyed optimist who would have been right at home with Jimmy Stewart in Capras mythical Bedford Falls.

For them, as well as the play's first director, Garson Kanin, the fact that the Franks were Jewish was incidental to their play's theme. In a famous passage, they even contradicted Anne's own words. In her book, she chided Peter for wanting to deny his Jewish identity saying, "We're not the only Jews that've had to suffer. Right down through the ages, there have been Jews and they've had to suffer." Astonishingly, Kanin dismissed the passage as "an embarrassing piece of special pleading."

Was Anne's diary "too Jewish?"

In the Goodrich and Hackett play, Anne says nothing of Jews but speaks instead of minorities through the ages. "The fact that in this play the symbols of persecution and oppression are Jews is incidental," explained Kanin. Their play ended with a line taken out of context about Anne's belief in the goodness of people. There was no mention of Anne's terrible and agonizing death in a Nazi death camp. Her awakening to a sense of Jewish spirituality which shines out from the complete version of "The Diary" was extinguished.

Meyer Levin had seen in the writing of young Anne a "voice" who could speak for the millions of anonymous victims. But the play and the movie which bore her name turned out to be very much like the Soviet monument placed at the site of the Babi Yar massacre where tens of thousands of Jews were slaughtered in 1941. The victims were mourned, but all mention of the fact that they were Jews and that they had been killed specifically because they were Jews, was omitted.

Levin spent the rest of his life obsessed by the silencing of his own play in favor of a less Jewish version. He accused Otto Frank of imposing his own assimilated identity on his daughter as well as succumbing to the influence of another assimilated Jew, the viciously anti-Zionist Lillian Hellman. Foolishly, he engaged in a futile lawsuit against Frank for fraud as well as the Goodrich/Hackett team for plagiarism.

Though he continued to produce a steady stream of novels with Jewish themes, the rest of his life was wasted tilting against the windmills of a literary and theatrical establishment which was uninterested in his story of the "real" Jewish Anne.

The complicated story of Levin's tragic obsession is well documented in two books that are worth reading: "An Obsession with Anne Frank: Meyer Levin and the Diary" by Lawrence Graver (University of California, 1995) and "The Stolen Legacy of Anne Frank" by Ralph Melnick (Yale, 1997). Melnick in particular backs up Levin's suspicions about Hellman and the political motives that led to the butchering of the diary.

The argument here goes far deeper than lines in a play or movie. The "Anne Frank" controversy went to the heart of how we all view the Holocaust. When Levin wrote a front-page review of "The Diary" in The New York Times Book Review in 1952, few were ready to write about the Shoah. Today, there are times when it seems as if many Jews wish to talk of nothing else.

Universalizing the Holocaust

But, just as Otto Frank blindly refused to see his daughter's diary as a "Jewish book," and thus asked Levin "do not make a Jewish play of it," many today also fear that the Holocaust will be seen as "too Jewish." They want to transform it into an experience from which all can learn and thus prevent other cases of mass murder. For them it is no longer a specific historic event but a metaphor for all suffering. In a quintessentially Jewish sort of messianism, these universalizers are all too ready lump Anne Frank together with every other sort of atrocity. Everyone can take a lesson from the Holocaust. But to take away the identity of the victims, as Hellman and company did with the permission of Otto Frank, was fraudulent.

The producers of the current production of the play on Broadway have attempted to rectify Hellman's butchery of "The Diary." There's more Jewish content, and the saccharine uplifting ending is replaced with a narrative about the ultimate fate of Anne Frank. While this production is a big improvement, like all attempts to universalize the Holocaust, it fails. This is still a banal play about an unspeakable subject.

For those who truly wish to go behind the bookcase and learn about the real

Anne Frank, my advice is skip the play and read the

2/15/98: Religious persecution is still a Jewish issue

2/6/98: A lost cause remembered (the failure of the Bund)

2/1/98: Economic aid is not in Israel's interest

1/25/98: Jews are news, and a fair shake for Israel is hard to find