A lost cause remembered

Marking the centennial of the failed ideology of the Bundists

By Jonathan S. Tobin

Yiddish is in. From Harvard to the spanking new National Yiddish Book

Center

in Amherst, Mass., to local schools and JCCs around the country, study

of

Nostalgia for the culture and especially the language of Eastern

European

Jewry is definitely in fashion among American Jewry these days.

This is, by and large, a good thing. Yiddish has an honorable place in

the

history of Jewish literature and thought. Even more, the emotions the

sounds

of Yiddish evoke among Jews of Ashkenazi descent -- even those who are

two or

more generations removed from Yiddish as a spoken language -- are a

tender

rememberance of generations past. In particular, it is closely

associated

with the millions who perished in the Holocaust.

The debates which raged among Jews two generations ago over whether

Yiddish

or Hebrew was deserving of primacy in Jewish life, are over. Hebrew, the

language of the Bible and modern Israel, always was and still is the

national

language of the Jewish people. Yiddish could no more assume that title

than Ladino --

the language spoken by Sephardic Jews. Only Hebrew embraces the past,

the

present and the future of all of Jewish civilization. And though Yiddish

ought to be preserved and respected, it is the study of Hebrew (in which

scandalously few American Jews have attained fluency) and not Yiddish,

that

educated Jews ought to devote themselves.

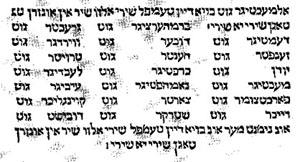

But largely lost amid the Yiddishist craze is the memory of the movement

that truly gave Yiddish life and purpose: The Bund. Few American Jews

outside of

college history departments or the Workmen's Circle Building in New York

City have even heard of it. But, on the eve of the Holocaust, the Bund

(officially known as the Algemeiner Yiddisher Arbeterbund fun Russland

un Poilen -- the

General Jewish Labor Federation of Russia and Poland) was the largest

Jewish

political movement in Poland -- the second largest Jewish community in

the

world at that time.

A forgotten centennial

Ironically, even as we celebrated the 100th anniversary of Theodor

Herzl's

convening of the First Zionist Congress this past summer, the Bund's

centennial passed largely without notice. Last month, about a hundred

Jews

gathered at the Greater Hartford Jewish Community Center to remember the

Bund with a historical lecture, Yiddish songs and the showing of a

Bundist film

made in 1939.

As historian Prof. Samuel Kassow of Trinity College pointed out at that

gathering, only weeks after Herzl placed the modern Zionist movement

onto

the world stage at Basel, Switzerland, a group of hardbitten Jewish

revolutionaries did the same for the Bund in Vilna. But, as Kassow

pointed

out, "there were no top hats and no cheers" at the Bund convention. The

Bund

delegates slipped into a nondescript house one at a time to evade police

surveillance. For days, they sat on a bare floor under a picture of

Marx,

debating Russian Socialist doctrine.

In part, theirs was a revolt against the low status of urban laborers in

Jewish culture as well as a protest against the persecution every Jew

faced.

Their goal was to create a movement which would strive to overthrow the

Czarist government of Poland and Russia while maintaining a separate

Jewish

workers' identity. Though they despised Jewish religion and tradition,

the

Bundists, unlike other Marxists, did not want the Jewish people to

disappear.

They had a utopian vision in which the Jews of Eastern Europe would live

and

work side by side with their Polish, Russian and Ukrainian neighbors.

They

believed Poles would "sober up" from the virus of antisemitism.

Their dreams became a sick joke

Today, after the Holocaust, and generations of antisemitic violence in

those countries even after the Nazis and the Communists, their dreams

sound like

"a sick joke," said Kassow.

The Bund was also characterized by a fervent opposition to Zionism, a

policy

they pursued up until the bitter end of Eastern European Jewry. When in

the

late thirties, the Revisionist Zionist leader Ze'ev Jabotinsky toured Poland urging

the

"evacuation" of European Jewry, the Bundists hurled abuse at him and

accused

him of abetting antisemitism! The Bund had their way: The Jews of

Poland

would stay and ultimately more than 90 percent would perish in the

crematoria of Treblinka and the rubble of the Warsaw Ghetto.

"No movement has ever failed so completely" as the Bund, concluded

Kassow.

Having allied themselves with a failed ideology that turned upon them in

the

Soviet Union (where Bundists were persecuted and murdered), and

uninterested

in escape from the deathtrap of Eastern Europe, the Bund lost everything

in

the Holocaust.

Visions of a doomed people

Yet, up until this tragic end, the Bund was far more popular among

Polish

Jews than the various Zionist movements. And for that Kassow had a

cogent reason.

Though they were wrong about virtually every important question that

faced

20th century Jews, they were often animated by a greater sense of

ahavas

Yisrael -- love of the ordinary Jew.

Zionists were sometimes more interested in building the Jewish future

than helping the Jew trapped in the present. Bundist achievements were

not inconsiderable. They organized Jewish self-defense against pogroms as well as trade unions. It helped transform

Yiddish from a colloquial jargon into a great literary culture. And

Bundist immigrants had a powerful impact on American Jewish life.

"They gave the Jewish worker a sense of dignity, of worth and hope,"

Kassow

said in his eulogy for Bundism. "They gave them a sense they were not

alone."

Viewing the Bundist film which portrayed Jewish children at the

movement's

youth camp, it was hard to keep back the tears as one stared into the

faces

of Jewish children who would almost certainly all be dead in less than

five

years. As they mouthed the socialist claptrap about the solidarity of

the

workers, one could dismiss Bundism as a bizarre, if picturesque, chapter

of

Jewish history.

One hundred years after Bundism was founded, we have no need for their

foolish political ideology or their sad rejection of Jewish tradition

and the land

of Israel. Their idea that Jewish identity could survive as a purely

secular

Diaspora phenomenon is an intellectual dead-end.

The Zionists were right about Jewish history, the Jewish future, and the

primacy of Hebrew. That is a fact that we should never forget even as we

celebrate

Yiddish is on the upswing.

Yiddish is on the upswing.

JWR contributor Jonathan S. Tobin is executive editor of the

Connecticut Jewish Ledger.

2/1/98: Economic aid is not in Israel's interest

1/25/98: Jews are news, and a fair shake for Israel is hard to find