As the Republican presidential hopefuls converged for their debate at the Ronald Reagan Library in Simi Valley, Calif., each was hoping to reap political advantage from the national TV exposure. But for most of the candidates who would appear on the stage, any hope of a surge was, at best, a longshot. After all, virtually every poll since the beginning of the campaign had shown the same candidate in the lead: the brash New Yorker with the multiple ex-wives and the take-no-prisoners style.

Is that a description of Donald Trump heading into last Wednesday night's CNN debate?

Or is it about Rudy Giuliani, heading into the GOP debate at the same Reagan shrine eight years ago?

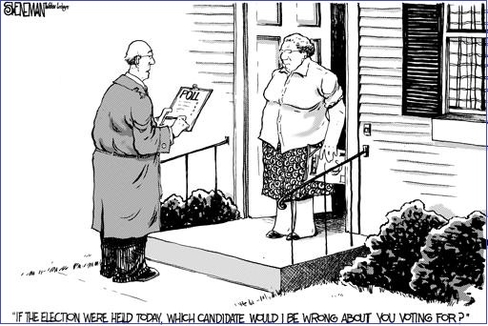

The fact that it could accurately describe either man tells us a lot about political opinion polls and how crummy they are — crummy not just because of how early it is in the political cycle, but also because of how far we've advanced into the digital age.

In the 2016 presidential marathon to date, the Trump phenomenon has been all the rage. Every new survey seems to confirm The Donald's perch atop the Republican heap. On Tuesday, a New York Times/CBS poll found 27 percent of GOP voters supporting Trump for the nomination, up from 24 percent in August. One day later, a Washington Post/ABC poll had him at 33 percent of Republican voters. At the state level, it's same thing: Recent polling in Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina by YouGov all put Trump in the lead. So does another survey in New Hampshire, conducted by MassINC for WBUR.

All of which proves exactly nothing about where the presidential race is going.

Eight years ago, it was Giuliani who was the seemingly unbeatable king of the GOP hill. "America's Mayor" was the hands-down frontrunner in almost every political poll — and there were scores of them — taken in 2006 and 2007. For months on end, he dominated the field. Yet in the end he won nothing — not even in the Florida primary on which he ultimately staked his candidacy. By the end of January, Giuliani had quit.

What was true of Giuliani's popularity early in the 2008 cycle was true of Howard Dean's at the same stage in the 2004 cycle. It was true of Rick Perry's, Newt Gingrich's, and Herman Cain's early in the 2012 cycle. Anyone can be the "frontrunner" in an election most voters aren't really thinking about yet. The 2016 New Hampshire primary is still 20 weeks away; the presidential election won't take place for more than a year. Today's political opinion polls supply fodder for media pundits and talking heads. But they have about the same predictive power as fortune cookies.

Yet will next year's polling be any better?

Early poll results have always been rubbish, but election polling itself is growing increasingly dubious. Last May, in a widely-noted blog post titled "The World May Have A Polling Problem," political statistician Nate Silver confessed that pollsters were in trouble. He was writing in the immediate aftermath of Britain's general election, when virtually every forecaster, relying on polling data, had failed to discern that David Cameron's Conservative Party was headed not for a razor-thin plurality in the House of Commons, but for an outright majority — a stunning result.

"There are lots of reasons to worry about the state of the polling industry," Silver wrote. The UK fail was only one in a string of recent high-profile elections that pollsters had botched. In November 2014, they didn't detect the Republican wave that swept nine US Senate seats from the Democrats, the largest Senate gain in a midterm election since 1958. Israel's election in March was thought to be a too-close-to-call battle between Benjamin Netanyahu's Likud Party and Isaac Herzog's Labor alliance. In the event, Likud won 30 seats, far surpassing the 18 it had held going into the election.

"Election polling is in near crisis," broods Cliff Zukin, a past president of the American Association for Public Opinion Research. "Our old paradigm has broken down, and we haven't figured out how to replace it." The reason? In a word, cellphones.

For decades, professional opinion polling has relied on the ability to call landline phone numbers generated at random and be fairly confident of reaching an adult at the other end. But the explosive growth in cellphone use over the past two decades has fatally undermined that confidence. Today, according to federal data, more than 45 percent of American homes only use cellphones; another 15 percent, though owning landlines, get almost all their calls on cellphones. Thus any pollster who relies on landline phones to survey public opinion bypasses close to 60 percent of US households right off the bat.

Alas, polling firms can't simply adjust to changing habits. Federal law prohibits the use of automatic dialers to reach cellphones, so pollsters must pay for cell numbers to be manually called — a much more costly proposition. Plus, Americans nowadays are rarely willing to take a pollster's call. Over the course of his career, Zukin writes, telephone response rates have plunged from 80 percent to 8 percent.

Those aren't the only hurdles tripping up pollsters. Far more Americans now cast absentee ballots, undermining exit polls that rely on interviewing voters at local precincts. Online polling is alluring, but many elderly voters are still not reachable via the Internet. And an old problem persists: what Britons call the "shy Tory" effect, or the wariness of conservative voters to tell pollsters how they intend to vote.

For better or for worse, polling's heyday is over. Political surveys are ubiquitous, but fewer and fewer of them will be correct. You know that bromide about how the only poll that matters is the one on Election Day? Time to start taking it to heart.

Last week a middle-aged businessman rescued five students from a lynch mob. Now the lynch mob is after the businessman, threatening to kill him for his act of bravery.

"I'm not a hero," insists the man, as heroes usually do. "I did it because I'm a human being."

The incident happened in Hebron, the ancient city in Israel's West Bank that today is largely controlled by the Palestinian Authority. Five yeshiva students, haredi ("ultra-Orthodox") tourists from America, took a wrong turn while driving to the Machpela Cave, the sacred burial site of the Biblical patriarchs, and suddenly found themselves under attack in one of Hebron's Arab neighborhoods. The students were assaulted with rocks and Molotov cocktails; their car was set on fire.

The mob was just beginning to beat them when a bystander intervened. Faiz Abu Hamadiah, a 51-year-old local resident, quickly propelled the students into his own house nearby, and sheltered them until Israeli security forces arrived nearly an hour later.

"As soon as we saw that a riot was starting," Hamadiah told a reporter, "my family and I managed to bring them inside. . . . We gave them water to drink and tried to tell them that they were safe, though they didn't speak Arabic."

For an unarmed man to save five intended victims from a frenzied mob takes remarkable courage under any circumstances. When the rescuer is a Palestinian Muslim in an all-Arab neighborhood and those he saves are strangers in conspicuously Jewish garb, the moral valor he displays is extraordinary — and a heart-lifting reminder of the goodness that people are capable of, however poisonous the atmosphere that surrounds them.

Jewish tradition famously teaches: "Whoever destroys a soul, it is considered as if he destroyed an entire world. And whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world." That teaching is so famous, in fact, that it is quoted in the Koran.

No society in history — not even the most decent — has ever wholly uprooted the lust to kill and terrorize. Israel comes closer than most; Muslim tourists who inadvertently take a wrong turn into a Jewish neighborhood will not find themselves under attack by a mob bent on slaughter. But the Jewish state has its savages as well, such as the arsonists who torched the home of the Dewabsha family in the village of Duma on July 31. An 18-month-old toddler, Ali, burned to death in the inferno; his father, Sa'ad, died a week later. On Monday, after weeks in a coma, Ali's mother, Reham, died of her injuries too.

Israelis across the political spectrum expressed shame and anguish in response to the arson attack. Many are sickened by the realization that such evil could come from within — and outraged that the murderers are still at large. The Palestinian man who saved five Jewish lives, meanwhile, finds himself reviled as a collaborator. Other Palestinians have reportedly threatened to "burn his house down, or cut off his head."

Heroism comes in different forms, but the greatest is the courage to act in defense of the despised outsider — especially when it would be more prudent to look the other way. Today we use the term "good Samaritan" to mean any charitable person. But 2,000 years ago, when Jesus related his parable about the Israelite who had been beaten and left for dead on the Jericho road, Samaritans and Jews hated each other. Bitterness between the two communities ran deep.

Yet it was precisely the Samaritan who saved the wounded Jew, choosing to ignore the stranger's detested tribal identity, and to see instead a fellow human being.

That Samaritan, like Faiz Abu Hamadiah, would no doubt have denied being a hero. The only difference between them is that the Good Samaritan was a parable. Hamadiah is blessedly, beautifully real.

Comment by clicking here.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author