THE END of the human race as we know it might be upon us. I refer not to some very distant, natural evolution of the human species — perhaps possible, perhaps not; in any event, unknowable to us. Rather, I refer to three prospective human interventions in the nature of humanity that, if let to proceed unfettered, will have farreaching consequences, namely, an end of the human race as we know it.

These three interventions are a radical tethering of humans to computers, a radical change in genetics, and a redefinition of gender. What each of these interventions have in common is speed. It takes far less time to effectuate radical change than at any time in history.

What these interventions have in common in a much narrower sense — the sense in which they are presented here — is that each is more complex than a column can allow for. But if we do not begin to face these issues, history may overtake us in ways we do not expect. So, for the sake of stimulating discussion, investigation and, possibly, action, here goes.

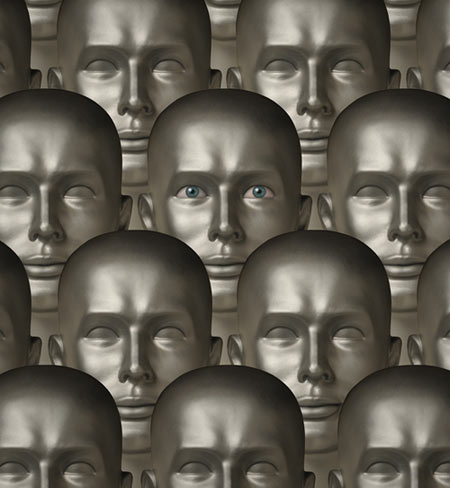

ROBOTIC, computerized humans. If you think that human beings, with their ceaselessly moving thumbs, with trillions of electronic messages sent or received daily, with the exponential jump in commerce and research online, is revolutionary, consider this: Human beings not separated from their computers, but unified with them.

Unified — not metaphorically, not behaviorally, not visually, but literally.

Imagine a day in which the computer is plugged into the brain or attached to other parts of the body. Imagine a day in which preprogrammed instructions drive not just a computerized robot, but the human being attached to it.

Imagine a day in which human behavior cannot proceed absent the input of a computerized robot directly into the biochemistry of the human being.

A dissolving line between the human and the robotic is not science fiction, but just around the corner.

Unfettered extension of the use of computerized robots from measuring to intervening in bodily functions will, no doubt, be presented as a boon to health. Perhaps it will indeed be a boon to the health of individual organs or cellular or intracellular processes. But along with these health advantages will loom a new shape to humanity — human beings no longer blessed with the free choice to take medicines, or not to take them, or to undergo procedures or surgeries, or not to; but human beings ruled by decisions that will be made by a computer, based on initial instructions programmed into it.

Look forward to intimations of this radical change in humanity as the range and sophistication of robots gain speed. The time to begin thinking about the ethics of the combination of robotic instruments and human beings is now.

GENETICS. David Baltimore and Paula Berg, both Nobel laureates, inform us in the Wall Street Journal (April 8) that the old-line racist nonsense of eugenics is now a technological possibility.

Hitler and Mengele thought they could breed a superior race. They did not know how; they only knew how to torture and murder. Today, however, it is now possible to alter not just somatic cells, the effects of which which are not transmitted to the next generation, but germ-line cells. Changes to these cells unalterably affect all future generations.

In what surely earns an award for understatement, Baltimore and Berg write: " . . . the decisions to alter a germ-line cell may be valuable to offspring, but as norms change and the altered inheritance is carried into new genetic combinations, uncertain and possibly undesirable consequences may ensue." Indeed.

But still more. " . . . germ-line modification would involve attempts to modify inheritance for the purpose of enhancing an offspring's physical characteristics or intellectual capability. . . . choosing to transmit voluntary changes to future generations involves a value judgment on the part of parents, a judgment that future generations might view differently." Indeed.

The authors ask for voluntary genome alteration to be outlawed at the present state of knowledge due to the unexpected consequences of a given gene alteration, which, if I understand this arcane expertise, is irreversible.

The counterargument is that germ-line alteration could prevent the transmission of a disease to offspring. However, the authors argue, there are different ways to achieve the same result without the risks entailed by germ-line genetic alteration.

The authors related that at a critical conference on genetics back in 1975, germ-line alteration seemed so far into the future that it was not seriously discussed. Now, human beings must choose whether to allow technology to march on unfettered by human values.

GENDER. Genesis 1:26 states, "And G0D created Man in His image, in the image of G0D He created him; male and female He created them."

Accept or reject the biblical account as you like, but it has hardly been surprising for millennia that human beings come in two distinct genders.

Later, in the second chapter of Genesis, it says that G0D formed man from the dust of the earth (2:7), that it was not good for the man to be alone (2:18), that G0D built woman from a rib of man (2:21-22), that G0D then said, "let a man leave his father and his mother and cling to his wife and they shall become one flesh" (2:24). Again, take the biblical story as you like, but starting here and continuing down through the religious and secular literature of humanity, the presupposition has always been two ineradicably distinct genders.

Perhaps no more. If a person can legally and socially define his or her gender by how he or she feels, then gender becomes a meaningless marker: feeling, not biology. This alters humanity as we have known it.

Some think this is wonderful — an expansion of human rights. Others observe that in both its legal and narrative segments, and not just in a verse here or there, the Hebrew Bible posits the reality and value of two distinct genders. Is Genesis, in specifying these two genders, and thus in saying that the human being is created "in the image of G0D," still relevant?

The prospect of a genderless, or a gender-fluid, humanity is not overwrought. A quarter of a century, short as it might be in the span of human history, has proven to be more than an adequate time span for a major evolution of human attitudes toward sexual orientation. Gender could be next. Genetics could be next. Robotic, computerized human beings could be next.

I DO NOT think it is too late for society to ask whether this is the future it wants. One thing is clear. This is a future that, if won, will be won in small, seemingly harmless steps. If this is the future you want, welcome these steps. Advance them. If this is not the future you want, do not be fooled, for example, that a school kid winning the right to use the bathroom of the sex that is opposite to his biological gender is an oddity. Not responded to, small steps like these will determine the social, genetic and medical future of humanity.

People speak of the great changes in civilization coming due to alterations in racial composition, or indistinct national borders, or nuclear proliferation. Large as these changes loom, they are not the major issues on the horizon of humanity.

Race to me is a purely neutral category; the racial composition of society is of no concern to me, one way or the other. Nationalism to me is still an important determinant of freedom, but admittedly not an inherent value; while nuclear proliferation is a critical risk to the human condition. But even if nationalism and nuclear proliferation go in the wrong direction — even then, short of the actual use of a nuclear weapon, these changes wold be nothing compared to the possibilities of human variation due to radical new approaches to robotics, genetics and gender.

One thing I think we can all agree on: These radical interventions in the human condition shouldn't just "happen," shouldn't be allowed to catch us, unawares. If we want one or more of these interventions, we should guide them. If we do not want one or more of them, we should oppose them.

Comment by clicking here.

Rabbi Hillel Goldberg is executive editor of the Intermountain Jewish News, where this first appeared, and the author of several books on biblical and Judaic themes. His writings have appeared in JWR since its inception.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author