The Senate negotiations that resume this week on the overhaul of the health care system are about many things — Medicaid spending levels, taxes, the opioid drug crisis, the number of Americans who will be uninsured. But this fight is only marginally about health care. It’s really about power and politics and the presidency.

Certainly the substance of the bill that emerges from the Senate — if one does emerge — is not insignificant. That bill will shape, though not determine, the profile of health care in the United States. But what is occurring in Washington this week is (and this should not astonish you) more about profile than anything else.

Here’s why. The Senate bill will differ from the legislation the House passed this spring, almost certainly in major ways. One important difference will be coverage of pre-existing health conditions — eliminated for some in the House version, likely retained in the Senate version — but there are many others. The two competing bills will go to a House-Senate conference committee, which operates under rules that are prescribed but not always applied. The result will be a compromise bill that will go to both chambers. That is when you should start paying close attention.

The unwritten but indispensable, immutable rule about lawmaking: Congressional legislation is like an NBA playoff game. You can pretty much ignore the first three quarters, and maybe part of the fourth quarter. It is the final few minutes that count. That’s when the game is won or lost. Shakespeare had it right: “What’s past is prologue.” It should not be lost on you that the phrase comes from a play called “The Tempest.”

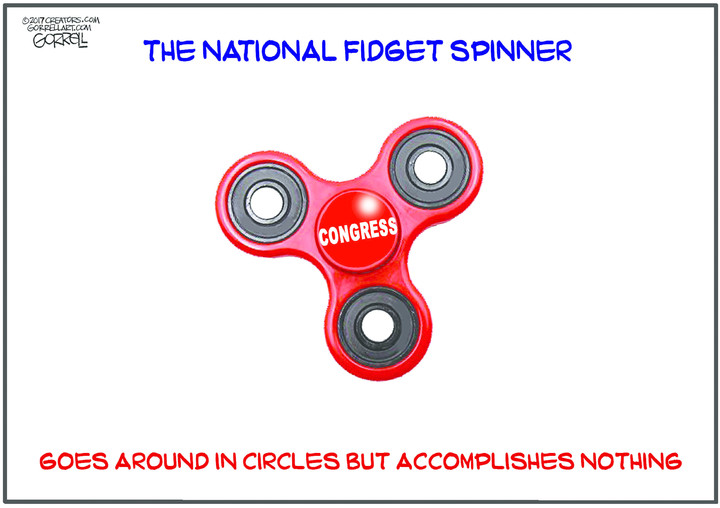

In the meantime, much of what is going on is tea-pot posturing. The theatrics, to be sure, have been compelling: closed-door negotiations by a committee not exactly marked by gender or ideological diversity, feverish lobbying, a rush to judgment.

Probably not since the Kansas-Nebraska Act in the run-up to the Civil War has such a major issue been shoved down the congressional throat as swiftly. In that case, Sen. Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri described the measure, crafted by another Democrat, Sen. Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, as “a silent, secret, limping, halting. Squinting, impish, motion — conceived in the dark — midwifed in a committee room, and sprung upon Congress and the country in the style in which Guy Fawkes intended to blow up the Parliament house, with his 500 barrels of gunpowder, hid in the cellar under the wood.”

If you think there are innumerable moving parts to the health care debate, you are right, and that is because there are innumerable, sometimes irreconcilable, motives in motion. Some have to do with health care, but these merely make up the platform on which other forces are at play — forces that have free rein because lawmakers know what the public has forgotten: that a bill passed in the Senate would be only a building block. Almost everything in it could be reshaped, replaced or repealed in conference.

Indeed, we know what really matters in the next week or so. This is the playbook:

The president. Throughout the 2016 campaign, Donald J. Trump, a man more of inclinations than ideology, spoke about “winning,” even warning, 17 months ago in South Carolina, “We gonna win so much you may even get tired of winning and you'll say, ‘Please, please, Mr. President, it’s too much winning! We can’t take it anymore!’ ” For Mr. Trump, the substance of health care legislation doesn’t matter so much as the fact of having overturned Obamacare.

The Republican lawmakers. They ran on repealing Obamacare and many of them have voted more than five dozen times to eliminate the Affordable Care Act — in roll calls that were meaningless because of the assurance that President Barack Obama would have vetoed the legislation. Now that the GOP controls the White House and both houses of Congress, they must make good on their promise, lest they receive the verdict that E.L. Godkin, the founder of The Nation magazine, rendered on William McKinley and the 56th Congress: “On the whole,” the magazine said, in consideration of Washington’s failure to address an isthmus canal in Central America, corporate trusts, tax cuts and the governing structures of the newly acquired territories of Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam, “this is not a review for a great party, secure in its possession of all branches of the Government, to be proud of.”

The Democratic lawmakers. Twice in nearly a century — during the Franklin Roosevelt and Barack Obama years — the Republicans have become the “Party of No,” basically defining themselves as being against pretty much everything the Democrats favored. Now, Democrats are playing that role, providing a united front against just about everything the Republicans and the president support. The Democrats’ dreary role here is to say no and then to bray to their supporters that they fought the good fight and kept the faith.

Next come the two unknowns that could define this era and actually shape the contours of the American health care system.

The first is whether the president and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky employ the tactic of winning support from Senate skeptics by understanding the NBA rule and saying to their wavering Republican colleagues: Vote for this bill in the full knowledge it’s not the final product. Your vote isn’t for the substance of this legislation, but for the process of legislation. Help get this bill to conference, where the real work occurs and where you may get your way. If you don’t get your way, well, vote against the conference report. But keep the process moving.

The second is whether the bill fails and the Senate is forced to do what it is supposed to do, and what the Democrats who created Obamacare failed to do: craft bipartisan legislation, this time to address the crisis of health care while minimizing the number of uninsured and preserving Americans’ sense of health security.

The first time a modern political party did that — put country ahead of party — was in 1935. That year, 81 House Republicans and 16 Senate Republicans — ardent foes of FDR, who was so odious to them that many would not even speak his name — nonetheless voted to create Social Security. Who says history doesn’t have lessons for the present, and who says history cannot repeat itself?

David Shribman, a Pulitzer Prize winner in journalism, is executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author