The American president was a romantic, a visionary, even a utopian. He was not without flaws; his racial views were offensive for his time, repugnant for ours. But he believed in human rights and the sanctity of human life. And he had a broad view of natural rights, and they included the freedom of the seas and the virtue of national self-determination. It was a toxic brew of ideas and ideals — it would produce rhetorical majesty and personal and national tragedy — but 100 years ago today he delivered the most important speech of his life, perhaps the most important speech of his time.

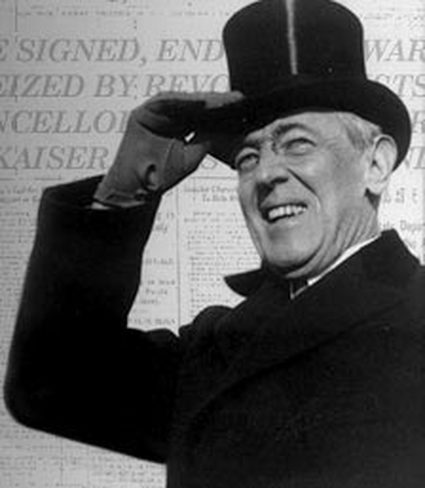

The son of a preacher, the product of Johns Hopkins and Princeton, a scholar and reformer, an introvert and an inveterate golfer, Woodrow Wilson strode to the podium of the House of Representatives on April 2, 1917, summoned every corpuscle of compassion and every calorie of energy he possessed, and bid the United States to abandon a century-and-a-quarter-old tradition of abstinence from the affairs of Europe and to join the Great War.

It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war, into the most terrible and disastrous of all wars, civilization itself seeming to be in the balance. But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts — for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free.

These were brave words at a time when Russia was in revolutionary tumult, Europe was in exhaustion and despair, and the conflict across the Atlantic seemed far away.

The immediate implication was clear. Americans — one of them was the young Harry Truman, who had worked at a farm, in a mailroom and for a bank — would travel beyond their home regions for the first time and they, and the country they returned to when the war ended 16 months later, would be transformed forever: more worldly, more engaged in the world, more regarded as an essential element in world affairs. World War I, as it came to be known after there was a second one, made a world of difference.

“The war made America more urban, more modern, more devoted to pleasure, licit and illicit,” wrote Will Englund in his new book, “March 1917.” It also made America committed to fighting dangerous foes and ideas on foreign lands lest their evils — Nazi genocide, Soviet tyranny and aggression, al-Qaida terror — reach our own land.

None of that was known when the 28th president opened his remarks. What was known was that the economic output of the United States had just surpassed that of the British Empire — an important fact for this war and for the following one — and that whether it remained on the sidelines in the war or moved to the center of the European conflict, the United States was moving to the center of global affairs.

“Henceforth, down to the beginning of the 21st century, American economic might would be the decisive factor in the shaping of the world order,” the historian Adam Tooze would write in his 2015 book, “The Deluge,” perhaps the most imaginative and insightful interpretation of World War I in a generation. Mr. Tooze, a Briton who teaches at Columbia, argued that Wilson wanted peace without victory — one of the president’s signature phrases — to assure that the United States “emerged as the truly undisputed arbiter of world affairs.”

That is a matter of substantial scholarly debate, but what is beyond debate is that Wilson’s war speech marked a significant inflection point in American life and politics. And, as presidents do when setting the nation on a course of conflict, Wilson spoke the language of grandeur and moral heroism — grandeur and heroism that would be debased in the sodden, contaminated trenches of wartime Europe.

Just because we fight without rancor and without selfish object, seeking nothing for ourselves but what we shall wish to share with all free peoples, we shall, I feel confident, conduct our operations as belligerents without passion and ourselves observe with proud punctilio the principles of right and of fair play we profess to be fighting for.

Not everyone wanted to enter this war. The isolationist Sen. William E. Borah of Idaho warned that once the United States was “in the maelstrom of European politics” it would be “impossible to get out.” Even a few years of Warren Harding-inspired “normalcy” wouldn’t disprove the Borah contention. The president knew that.

“Wilson knew full well war’s awful consequences, and he was keenly aware of the terrible risk he was taking,” wrote John Milton Cooper Jr., the University of Wisconsin historian and Wilson biographer. “Yet given his temperament it would have been nearly impossible for him not to choose war.” The president concluded his remarks to Congress this way:

To such a task we can dedicate our lives and our fortunes, everything that we are and everything that we have, with the pride of those who know that the day has come when America is privileged to spend her blood and her might for the principles that gave her birth and happiness and the peace which she has treasured. God helping her, she can do no other.

That last sentence was an adaptation of the famous exhortation of Martin Luther. “Mr. President,” said Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge, “you have expressed in the loftiest manner possible, the sentiments of the American people.” Two years later the Massachusetts Republican would defeat the president’s plan for American entry into the League of Nations.

One of the 50 House members who voted against entering the war was Rep. Jeannette Rankin of Montana, a pacifist and the first woman to serve in Congress. Decades later, she returned for a second term, and was the only lawmaker to oppose entering World War II. In her late 80s, she would lead a march against the Vietnam War.

The great British historian A.J.P. Taylor once reflected on the European turmoil of 1848 and said that “German history reached its turning-point and failed to turn.” The United States reached its turning point in 1917, and turned.

David Shribman, a Pulitzer Prize winner in journalism, is executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author