Earlier this month, two important Republicans — one the president of the United States, the other a onetime Rhodes Scholar who was a high-profile governor — weighed in on the same day on the state of the Republican Party.

In the morning came the assessment of former Gov. Bobby Jindal of Louisiana, expressed in an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal:

“The GOP will not be a populist conservative party as long as the current congressional leadership is in place. These leaders would rather lead a shrinking GOP to contain and crush the populist uprising.”

A few hours later, President Donald J. Trump, speaking at the Republicans’ congressional retreat in West Virginia, made these remarks:

“You know, Paul Ryan called me the other day, and I don’t know if I’m supposed to say this, but I will say that he said to me, he has never, ever seen the Republican Party so united, so much in like with each other. But, literally, the word ‘united’ was the word he used. It’s the most united he’s ever seen the party, and I see it, too. I have so many friends in this group, and there is a great coming together that I don’t think either party has seen for many, many years.”

What are we to make of this?

My answer: Mr. Trump is both right — and wrong. In that order.

He was right — note the past tense in a situation that is deeply tense — in seeing a new future for a new Republican Party with new contours. That perception animated his landmark 2016 campaign, when he defeated the most impressive field of potential Republican nominees since 1988 and perhaps since Gov. Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, Sen. William H. Seward of New York and former Rep. Abraham Lincoln of Illinois competed for the party’s 1860 nomination.

During that campaign, Mr. Trump experienced a benign political form of auditory verbal hallucination: hearing voices without speakers. Those voices turned out to represent a huge mass of voters who didn’t speak in conventional political terms and who, spurred by the Trump campaign appeal, upended American politics, perhaps destroying the political party that offered Mr. Trump its nomination even as he was railing against its principals and principles.

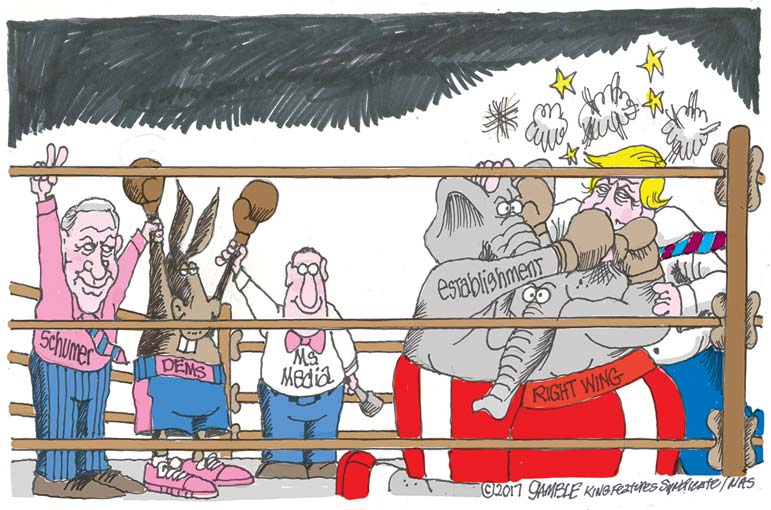

But Mr. Trump is wrong — note the present tense — when he asserts that the Republican Party of which he is the titular head is united. It’s not. Searching for a new identity, wary of an uncertain future, without a coherent vision of its role and deeply skeptical of its leader, the Republican Party is more distressed than any governing party since the Democrats of the late Lyndon Johnson years.

“On some issues the [Republican] party is united; taxes is one of them,” Judd Gregg, a former senator and governor of New Hampshire who is considered a wise party elder, said in an interview. “But on other issues — immigration, dealing with the deficit — there is a distinct difference of opinion. I’m not sure these differences are debilitating or unusual. There’s always been a lot of difference on issues. But the bigger issue is the president’s style. A lot of people find it difficult to take and feel that these tweets in the middle of the night undermine his effectiveness as president and thus are hurting the Republican Party.”

This is where Mr. Jindal, a former congressman and two-term governor of Louisiana, comes in. He was one of those presidential candidates eclipsed by the Trump campaign in 2016 and he has retired, at least for the moment, from elective politics — but not, apparently, from the political wars.

“We need to take over and reinvent the GOP,” he argues. “Mr. Trump won’t be the man to do it. We should create a more populist — Trumpian — bottom-up GOP that loves freedom and flies the biggest American flag in history, shouting that American values and institutions are better than everybody else’s and essential to the future.”

Some Republicans believe that Mr. Trump merely filled a vacuum — a vacuum, the veteran GOP consultant Alex Castellanos says, created by the Republican Party itself.

“When we talk about who enabled Donald Trump, it’s not the people who supported him but the Republicans who failed to lead,” he argued in a telephone conversation. The remedy: “a new generation of Republicans with views different from those of the old.”

Some of these new Republicans surely are the onetime Democrats who flocked to the party as a result of the Trump entreaties. (Many of them, or their philosophical forebears, drifted into the GOP during the Ronald Reagan years only to drift back by the allure of Bill Clinton or Barack Obama.) But some of them may be found in unfamiliar, unlikely places — and they may themselves have grave reservations about what they believe are alienating Republican positions (on social issues like abortion) or on what they perceive as dark Republican impulses (on race or gay rights).

The new Republican target may well be the high-tech enclaves in the state that Hillary Rodham Clinton won with a 4.3 million vote margin over Mr. Trump.

“I see the new Republicans in Silicon Valley, in tech — people who are living the principles Republican Party was built on and are living the principles of an open economy and an open education system,” said Mr. Castellanos, who was a top adviser to Southern conservatives, such as the late senators Strom Thurmond of South Carolina and Jesse Helms of North Carolina, and also to conventional Republican presidential nominees, such as Bob Dole, George W. Bush and Mitt Romney. “The Republicans have things they hate, but they are living the Republican ethos.”

But this is a hearts-and-minds conundrum for the Republicans.

Republicans have spent the last half-century saying that various groups — middle-class blacks, or working Hispanics, or upper-middle-class gays — have Republican minds. In each case, the party leaders never have been able to win their hearts fully. (They have come closest with Hispanics with Cuban roots. It is thus no coincidence that Mr. Trump has muted Obama-era overtures to the island nation.)

Though the GOP controls the White House and both houses of Congress, the effort to make the Republicans America’s natural party of governance involves more than outreach. It involves keeping the current Republicans in the fold even as the party seeks in invite others in.

David Shribman, a Pulitzer Prize winner in journalism, is executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author