|

|

Jacob Sullum

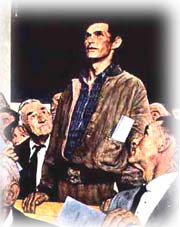

In the Norman Rockwell painting "Freedom of Speech," an earnest Everyman stands at a

public meeting to offer a question or comment. Judging from his mild expression and the

polite attention of the people around him, he is not saying anything offensive or threatening.

Maybe he is asking for a new stop sign,

The painting nicely captures how most Americans view the First Amendment, which they

love in theory but often abhor in practice. They are proud to protect freedom of speech, as

long as the speech does not stray too far from Rockwell's warm and fuzzy image.

The pamphlet that got nine Florida high school students arrested in late February was

anything but warm and fuzzy. The 20-page, mostly handwritten booklet ridiculed people with

"African diseases" and a weak grasp of English. It included drawings depicting a rape, a

head with a bloody fork sticking out of it, and the school's black principal, Timothy Dawson,

impaled on a dart board. "What would happen if I shot Dawson in the head?" mused the

author of an article entitled "A Student's Complaint."

Five girls and four boys distributed about 2,500 copies of the pamphlet at Killian High

School in Kendall, a Miami suburb. For disrupting school with this inflammatory material,

they were suspended, which is pretty much what you'd expect. But they were also arrested

and charged with a felony, which transformed a local embarrassment into a national news

story.

The teenagers ran afoul of a 1945 criminal libel law prohibiting anonymous publication of

material that "tends to expose any individual or any religious group to hatred, contempt,

ridicule or obloquy." Florida's "hate crime" law, which enhances penalties for offenses

motivated by animosity toward a racial, ethnic or religious group, bumped this first-degree

misdemeanor up to a third-degree felony. The Killian High pamphleteers therefore faced a

penalty of up to five years in prison.

Since he was personally attacked in the pamphlet, the principal's overreaction is perhaps

understandable. It's harder to fathom why the school district defended his decision to throw

the kids in jail. "The arrests were made, and we stand by that decision," said Henry Fraind,

deputy superintendent for Miami-Dade County Public Schools. "They do not have the right

to incite the feelings of outward racism."

The thing is, they do. The First Amendment protects both the right to engage in anonymous

speech and the right to express racist views. There's no question that Florida's criminal libel

law would be overturned by the courts if it were challenged.

The state attorney in Miami acknowledged as much a few days after the arrests, when she

said her office had dropped the charges because Supreme Court rulings "render the

statute in question unconstitutional and unenforceable." She nevertheless defended the

arrests, saying, "This has been a difficult decision because the document in question does

contain language and drawings of an outrageous and highly offensive nature."

The decision should not have been difficult. It's scary that the chief prosecutor in a major

American city seems to think that the question of whether people can be jailed for

something they said hinges on how outrageous it was. After all, when speech is punished,

it's usually because it offended someone.

Seduced by a Norman Rockwell vision of the First Amendment, Americans too often forget

that freedom of expression was a controversial notion for most of human history not

because our ancestors were benighted fools but because they recognized that speech is

often pernicious. The classical liberals who opposed censorship did not claim that all

speech was equally worthwhile, but they did insist that a central authority could not be

trusted to sort the good from the bad.

That conviction means we are obliged to tolerate all sorts of garbage, some of it much

worse than the puerile rag distributed at Killian High School. Sadly, the students who

produced the pamphlet, which included an excerpt from the First Amendment, seemed to

understand that point better than school administrators or local law enforcement officials.

The authorities may have hoped that a night in jail would teach these kids a lesson, but

instead it transformed a bunch of obnoxious jerks into free-speech martyrs. Call them the

Killian

Felonious Speech

Felonious Speech

complaining about an unfilled pothole or

suggesting a raffle to raise money for the next Founders' Day celebration. Whatever it is,

chances are he'd be able to say it without a constitutional guarantee.

complaining about an unfilled pothole or

suggesting a raffle to raise money for the next Founders' Day celebration. Whatever it is,

chances are he'd be able to say it without a constitutional guarantee.

02/20/98: Rules of the game

02/13/98: Feeling his pain... and a little pleasure