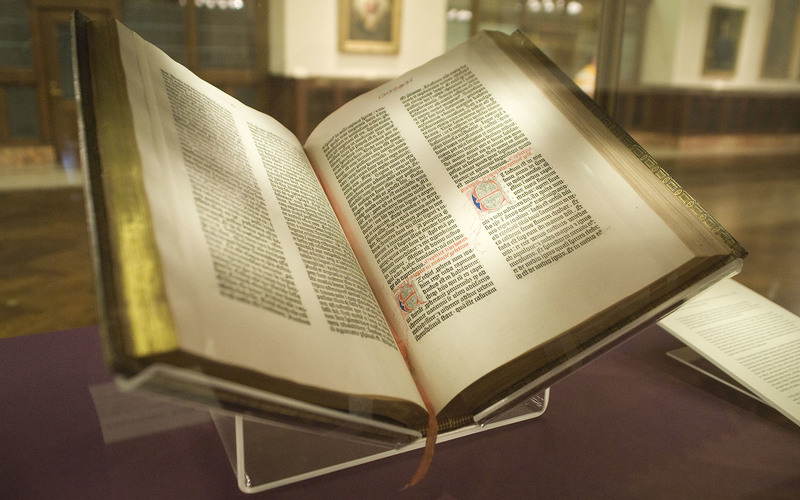

The Gutenberg Bible

The Gutenberg Bible

Fake news is everywhere, cluttering desktops, iPads, laptops, iPhones and all the other manifestations of the post-literate era when it's just too much trouble to find a reliable read.

Who needs to read when there's such an abundance of twits clogging up Twitterworld with the trivia, the trifling and the picayune — misinformation, usually the work of innocents, and disinformation, always the work of rogues spreading deliberate lies, exaggerations and confusion.

Farhad Manjoo, a technology correspondent for The New York Times, was tired of it all. Six months ago, he turned off all his digital news notifications, unplugged social networks, said goodbye to the cacophony and other noise of the news feed and took the radical step of subscribing to, of all things, three ink-on-paper newspapers and a weekly magazine.

He wanted to "slow-jam the news" but still wanted to know what was going on in the world. He was determined to find sources that furnished depth and prized accuracy over speed. It was an experiment, relying on print for news and not on "social media." He learned several interesting things.

What he learned first was that the traditional formula taught to generations of cub reporters — the opening paragraph must answer the five W's, who, what, why, when and where, and sometimes the how — is no longer in the curriculum. It's now, he discovered, "more like a never-ending stream of commentary, one that does more to distort your understanding of the world than illuminate it."

Commentary precedes and overpowers facts. The point of the story is often submerged in the 12th paragraph, sometimes deliberately so, where a reader may never see it because he gave up after the third paragraph. Relying on social media for the news, Mr. Manjoo learned, "is what other people are saying about the news rather than the news [itself] and that makes us susceptible to misinformation."

Perhaps the most important thing he learned is that it takes time, and experience and willingness, to sort fact from fiction and a lot of "news" on the Internet has never been sorted out. "Smartphones and social networks are giving us facts about the news much faster than we can make sense of them, letting speculation and misinformation fill the gap." He might have included disinformation, too, because disinformation, the deliberate fuzzing and invention of facts, is worst of all.

The sorting of fiction from facts, he discovered, "was the surprise blessing of the newspaper. I was getting the news a day old, but in the delay between when the news happened and when it showed up on my front door hundreds of professionals had done the hard work for me."

Just about every problem with understanding the news, he learned, "is exacerbated by plugging into the social-media herd. The built-in incentives on Twitter and Facebook reward speed over depth, heat takes over facts and seasoned propagandists over well-meaning analyzers of news."

Some of what Mr. Manjoo discovered is old news to the old-timers in the trade, who learned the trade in a different time, and who are now waiting for a flight (with connections to Atlanta) to the great newsroom in the sky. There's even a new study that confirms the grumpy conclusions of the old guys. Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology tracked thousands of news stories on Twitter, and these stories were tweeted millions of times between 2006 and 2017.

The researchers found — surprise, surprise — that fake news spreads much faster than real news. This confirms the familiar adage that a lie can go half-way around the world before the truth gets its boots on.

A weakness of the MIT study, published in Science magazine, is that it relied on several fact-checking organizations, some of which are susceptible to liberal notions of what's a fact and what's not, to determine what is false and what is not. The researchers were reassured that the judgments of the fact-checking organizations "overlapped more than 95 percent of the time." That might reassure the researchers, but it won't reassure me.

The researchers learned (duh!) that bad news, scandalous news, and even unlikely news, travels fastest. Everybody wants novelty, and the saucier and the naughtier, the bloodier and the more tragic, moves fastest. In the aftermath of the Boston Marathon massacre, Twitter exploded with "news." But what the researchers learned is that "a good chunk of what [they] were reading on social media was rumors."

Gutenberg's movable type and the printed page, barring a miracle, will never replace the computer screen. The profitability of newspapers will depend ever more on the "clicks" and "hits" its news items attract. This gives the advantage to the sloppy, the careless, and the reckless, and the careful reader should find a reliable printed page, hold it while he can, and read all about it.

Comment by clicking here.

JWR contributor Wesley Pruden is editor emeritus of The Washington Times. His column has appeared in JWR since March, 2000.

Contact The Editor

Contact The Editor

Articles By This Author

Articles By This Author